Glad Tidings of Benevolence

Twenty years after 'Shock and Awe', Moises Saman reflects on his role as a photojournalist covering the US-led invasion of Iraq and its aftermath. Interview by Colin Pantall.

Two decades ago, on March 20, Moises Saman was standing atop the Palestine Hotel in Baghdad, witnessing the first waves of Operation ‘Shock and Awe,’ — the beginning of the US invasion of Iraq in 2003. He photographed the bombs and missiles targeted on government ministries across the River Tigris; he photographed the flames and the smoke smearing across the night sky.

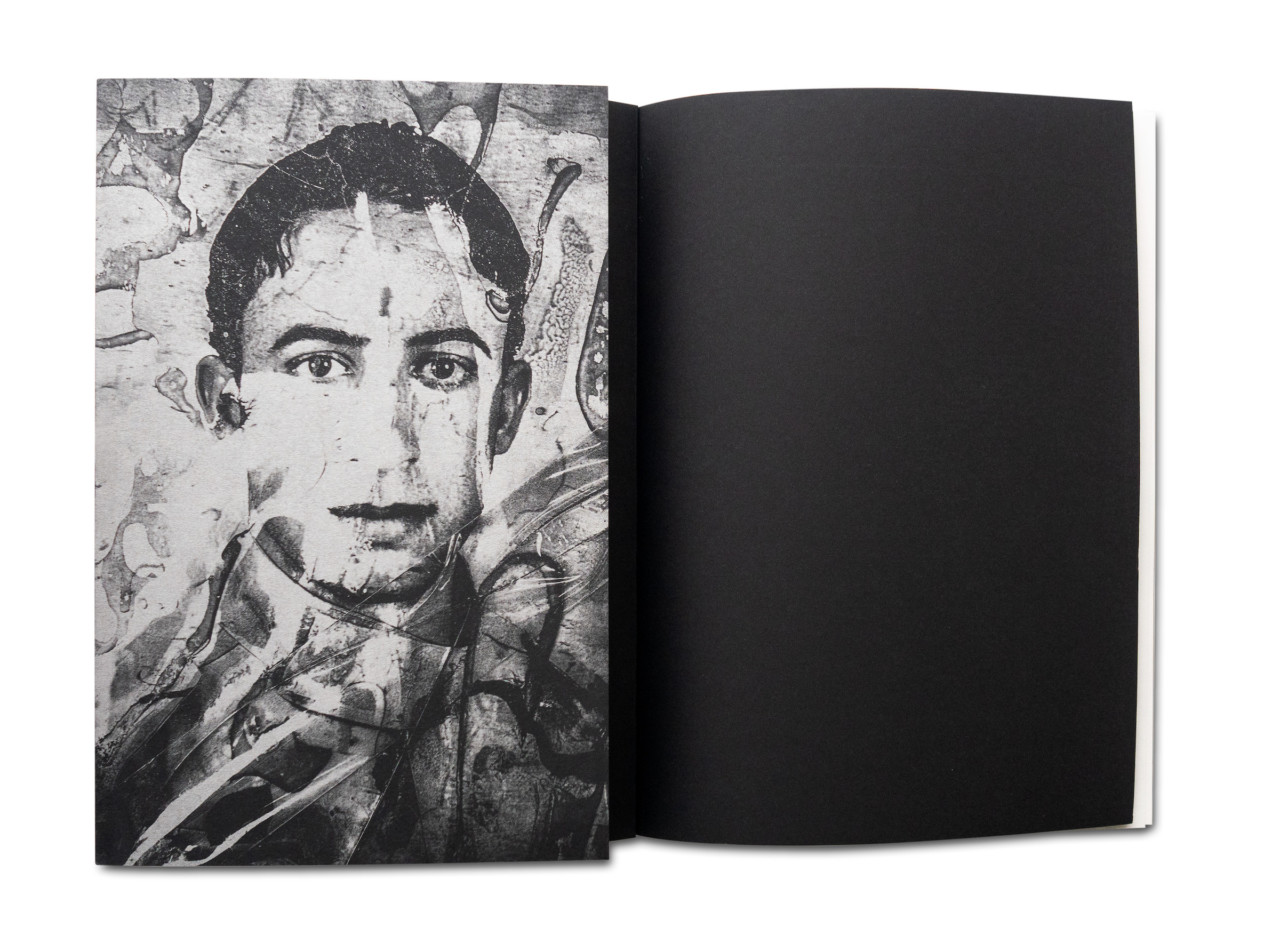

These were the first photographs Saman made of a conflict that has continued in various forms for 20 years — photographs that he is now deeply ambivalent about. What is not shown in these photographs is often more relevant than what is seen, he now believes.

“During those first days up on the rooftop of the hotel, there was no way to really grasp the fear of the millions of people that were hunkering down in their homes, holding their children while these bombs were going off,” he reflects. “Operation Shock and Awe seemed almost like it was made for TV. And we were part of that coverage, photographing from these vantage points at a distance that really failed to grasp the uncertainty and the fear; that failed to grasp the significance of the moment for Iraq, the US, and the world.

“There were no human faces on those front-page covers of Western newspapers the next day. It was all about the spectacle and the display of power,” Saman recalls in an online interview from his home in Boston, where he is currently completing a Nieman Fellowship in Journalism at Harvard University.

"There were no human faces on the front-page covers of Western newspapers the next day."

-

Just over a month later, on May 01, US President George W Bush stood on the deck of the SS Abraham Lincoln and proclaimed, “Major combat operations in Iraq have ended. In the battle of Iraq, the United States and our allies have prevailed.”

Except they hadn’t. And over the following two decades, Saman continued to photograph the unfurling conflict; the violence, the protests, and much else besides. His new book, Glad Tidings of Benevolence, published by Gost Books on the 20th anniversary of the invasion, is a record of those following years.

From the preamble to the 2003 attack and the execution of Saddam Hussein that followed three years later, it leads on to the sectarian violence that beset Iraq under occupation, to the rise of ISIS, and right up to the anti-corruption demonstrations of last year. It shows a conflict in continuous flux, one where multiple players play multiple roles, where nothing is clear, where rhetoric and reality never add up.

"'It became harder to live up to the role of a journalist — being the perennial, objective, distant observer, the uninvolved witness."

-

“When I started, there were times when I was thinking about my career,” he admits. “I was thinking about capturing the drama that would get [my photographs] on the front page. A lot of the time you don’t understand what’s happening around you. You’re not true to yourself about why you are there and what your motivation is. It’s important to be honest with yourself at some point.

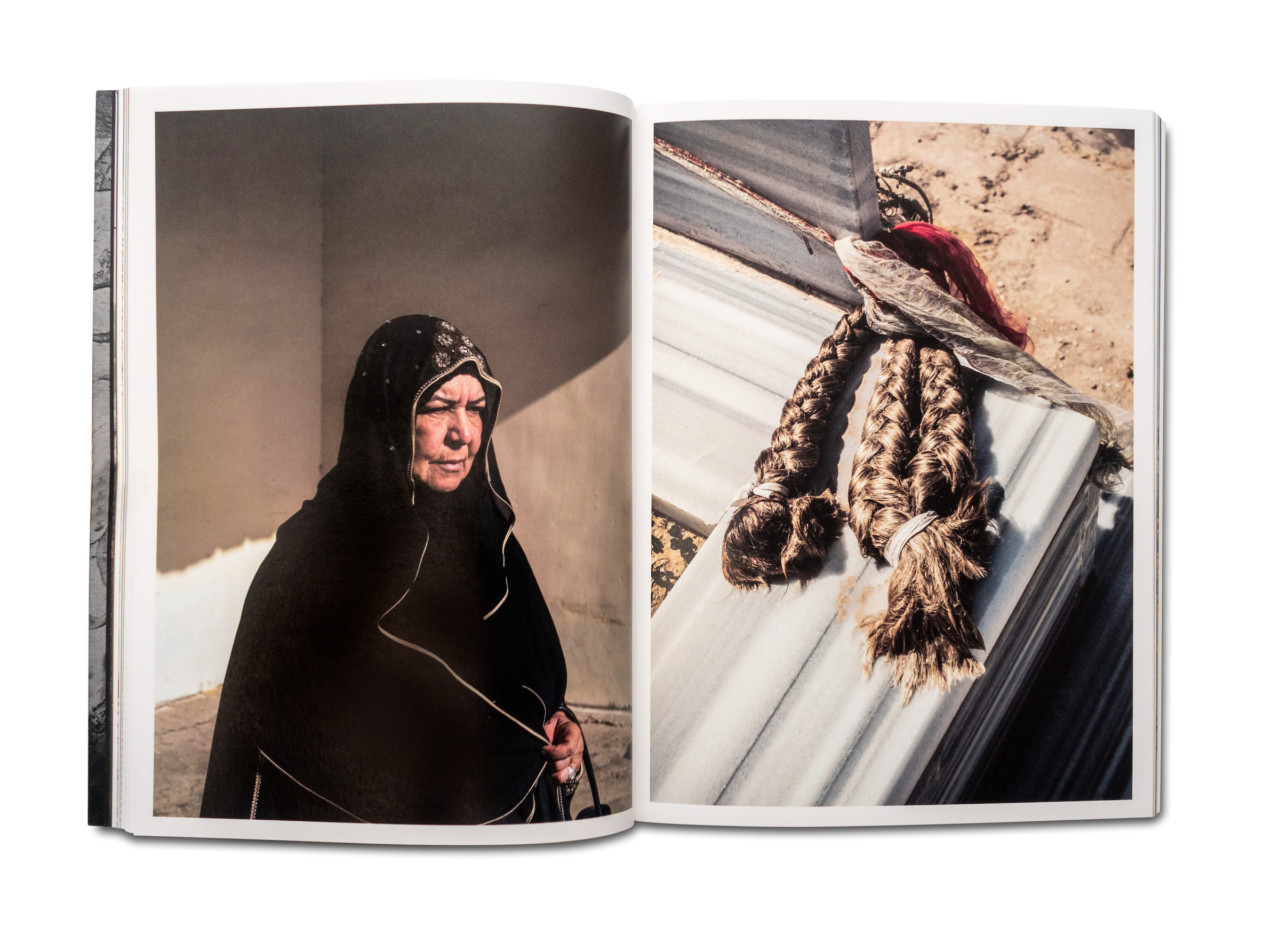

“Over time, as the war revealed more of its ambiguous, uncertain and confusing nature, it became harder to live up to the expectations associated with the role of a journalist — being the perennial, objective, distant observer, the uninvolved witness. I found myself more and more drawn to capturing alternative frames, those quieter moments defined by nuances and ambiguities that center human dignity, that give face to Iraqis who live every day with the immense challenges of insecurity, violence, and poverty.“

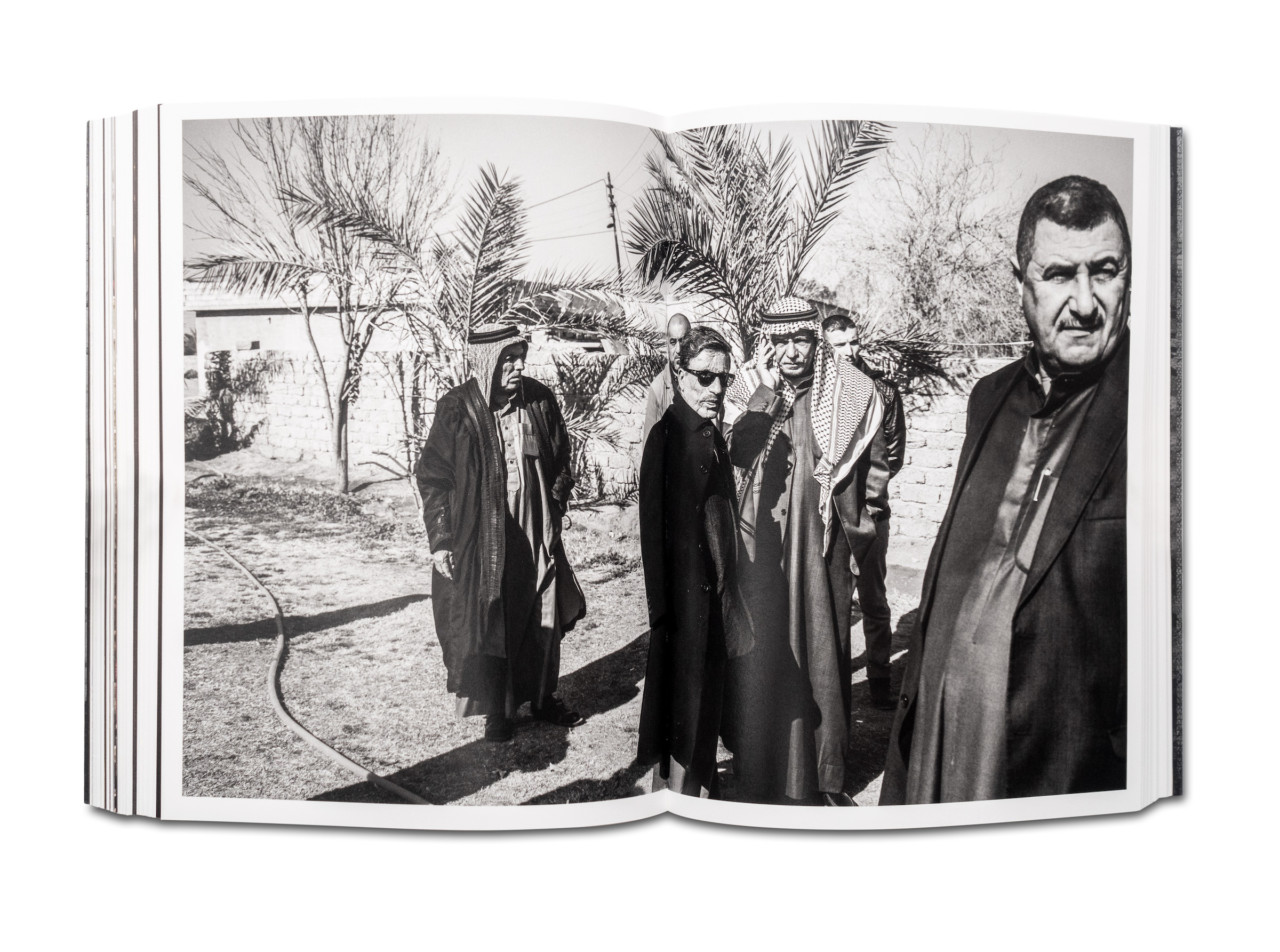

For example, in 2006, when Sunni Iraqis joined forces with the US military to fight al-Qaeda, I saw up close how quickly the Americans were able to redefine the narrative of the war. Insurgent leaders with blood on their hands were recast as allies in the ‘Sunni Awakening.’ I began to realize that I needed to take a different approach to be able to capture the ambiguity of those situations.

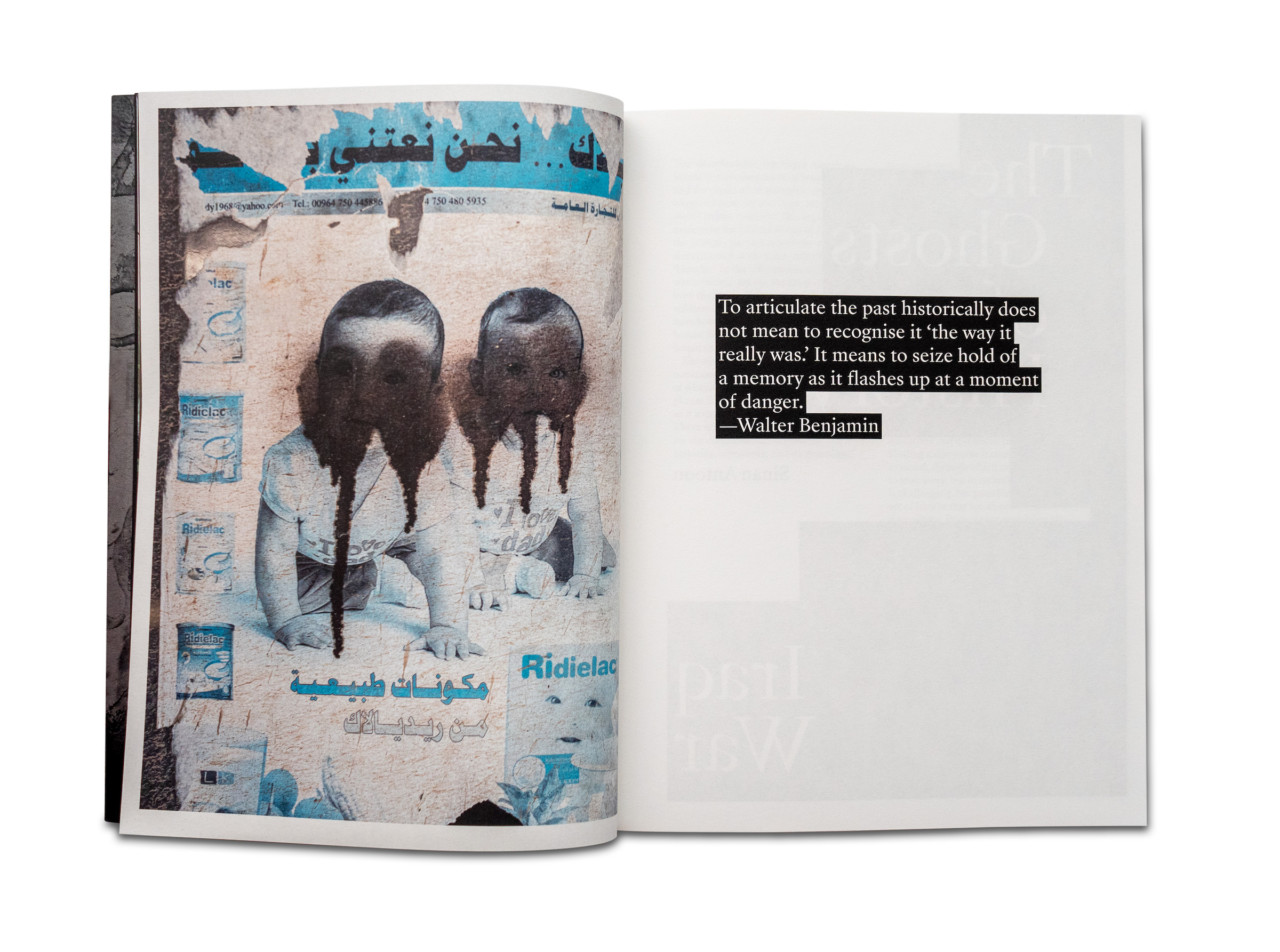

More than being just a record, the book questions the role of a photographer amid competing narratives of conflict; of whose story gets told, whose suffering is remembered. “Making this book was an attempt to make visible what [US philosopher] Judith Butler called “the framing of the frame.” I interpret that as the determination of what’s visible, what’s not, what stories are in the foreground, and what gets relegated to the background.”

"What stories are in the foreground, and what gets relegated to the background?"

-

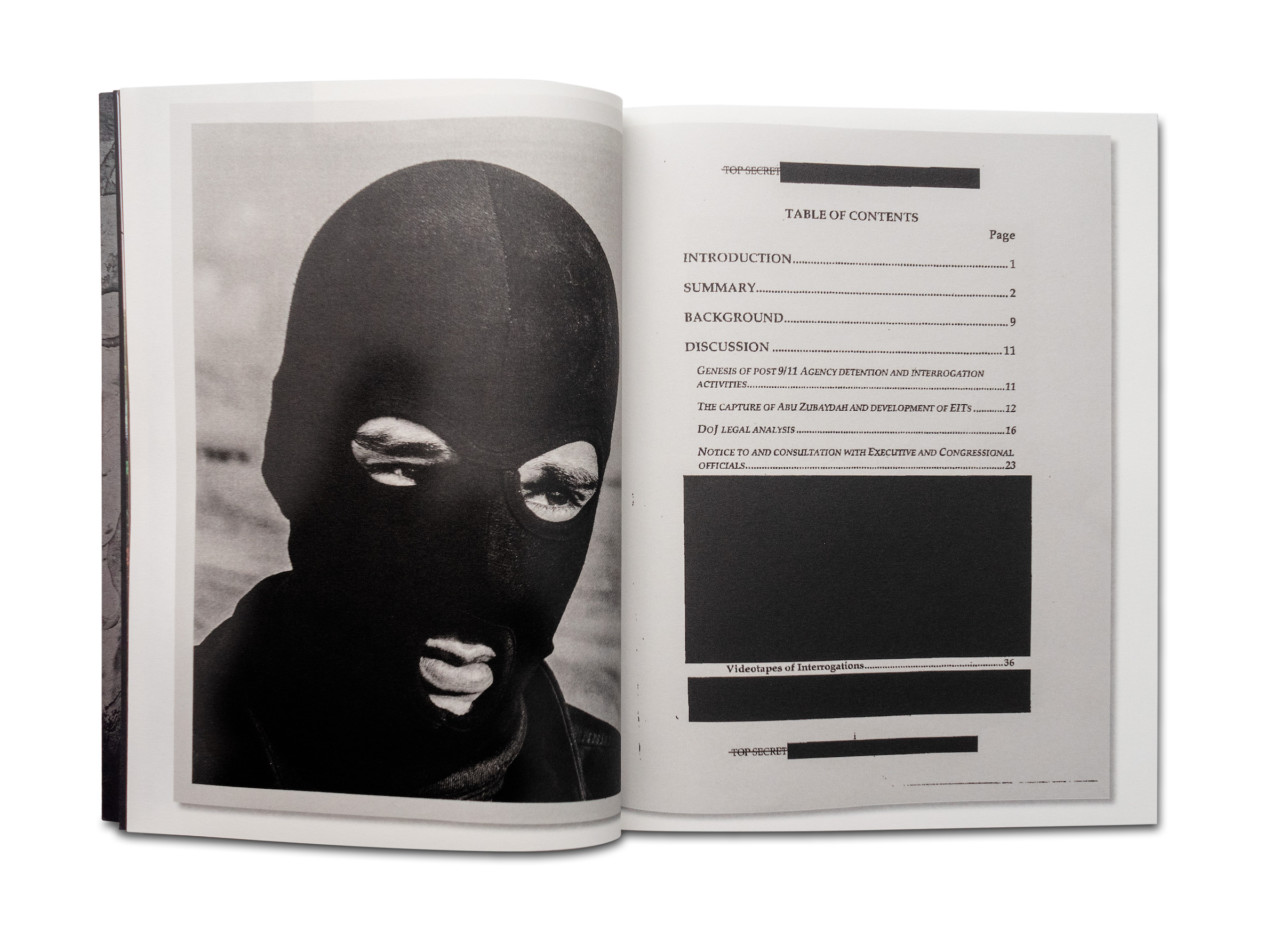

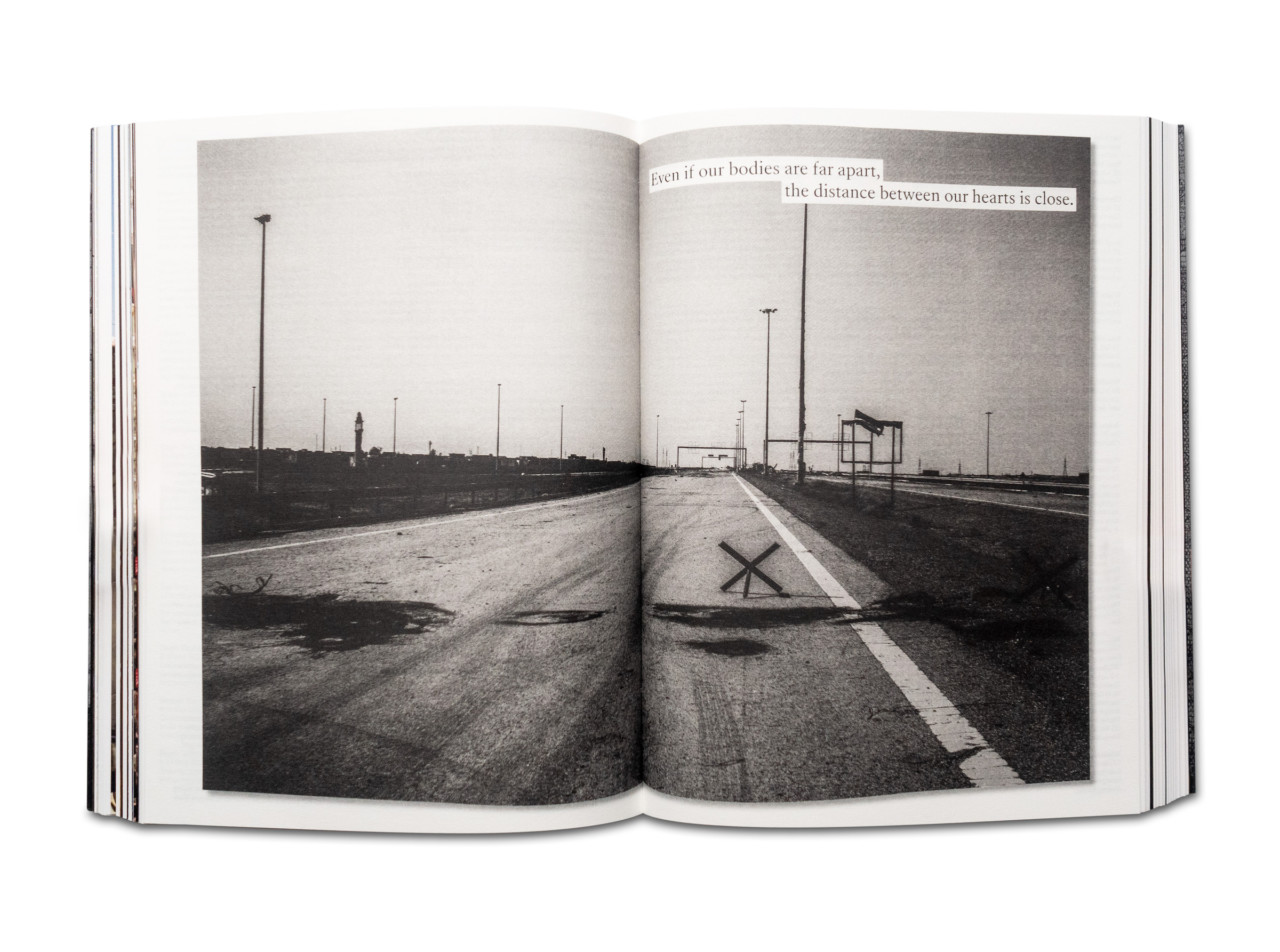

Snippets of text are threaded throughout the book. There’s a heavily redacted document showing the words, “permissible interrogation technique.” On the facing page, the words “the water board” stand out from the inky blackness.

There are lines from the song American Idiot by Green Day, and from the film Team America, and extracts from A Soldier’s Guide to Iraq. “Don’t cause unnecessary destruction,” reads one line from the latter. “Don’t abuse EPWs (Enemy Prisoners of War),” reads another.

There is religious imagery on the death cult of martyrdom. Elsewhere, the words of Bush and UK Prime Minister Tony Blair are writ large: “Lead me into war,” “You know that I believe in you,” “I just want you to know that, when we talk about war, we’re really talking about peace.”

Saman explains the inclusion of these additional texts and vernacular images is to illustrate “the way that actors from ISIS, from the political world, from pop culture, from these redacted official documents, all represent different attempts to shape the narrative.”

"They were creating their own lexicon of war."

-

This framing of the narrative is most evident in the list of operations that Saman includes. “The title of the book, ‘Glad Tidings of Benevolence’, comes from this code name the Americans put to one of the thousands of operations they made in Iraq. This is a recurrent theme in the book as well. The names of the sub-chapters come from these code names.“

Many of the code names read like a rash of the sub-Marvel straight-to-streaming B-Movies you might find in the depths of Netflix: ‘Rogue Thunder,’ ‘Iron Reaper,’ ‘Viper Pursuit.’ Code names such as ‘New Hope,’ ‘Restore Peace,’ and ‘Goodwill’ represent the greetings card end of the spectrum, but mostly the list has a hard, adolescent, metallic edge to it.

“They were creating their own lexicon of war. I became fascinated by these code names. I had a list of hundreds of them and began digging into what the actual missions were and what happened in them. Trying to get beyond the irony of naming these events where people died was very sinister.”

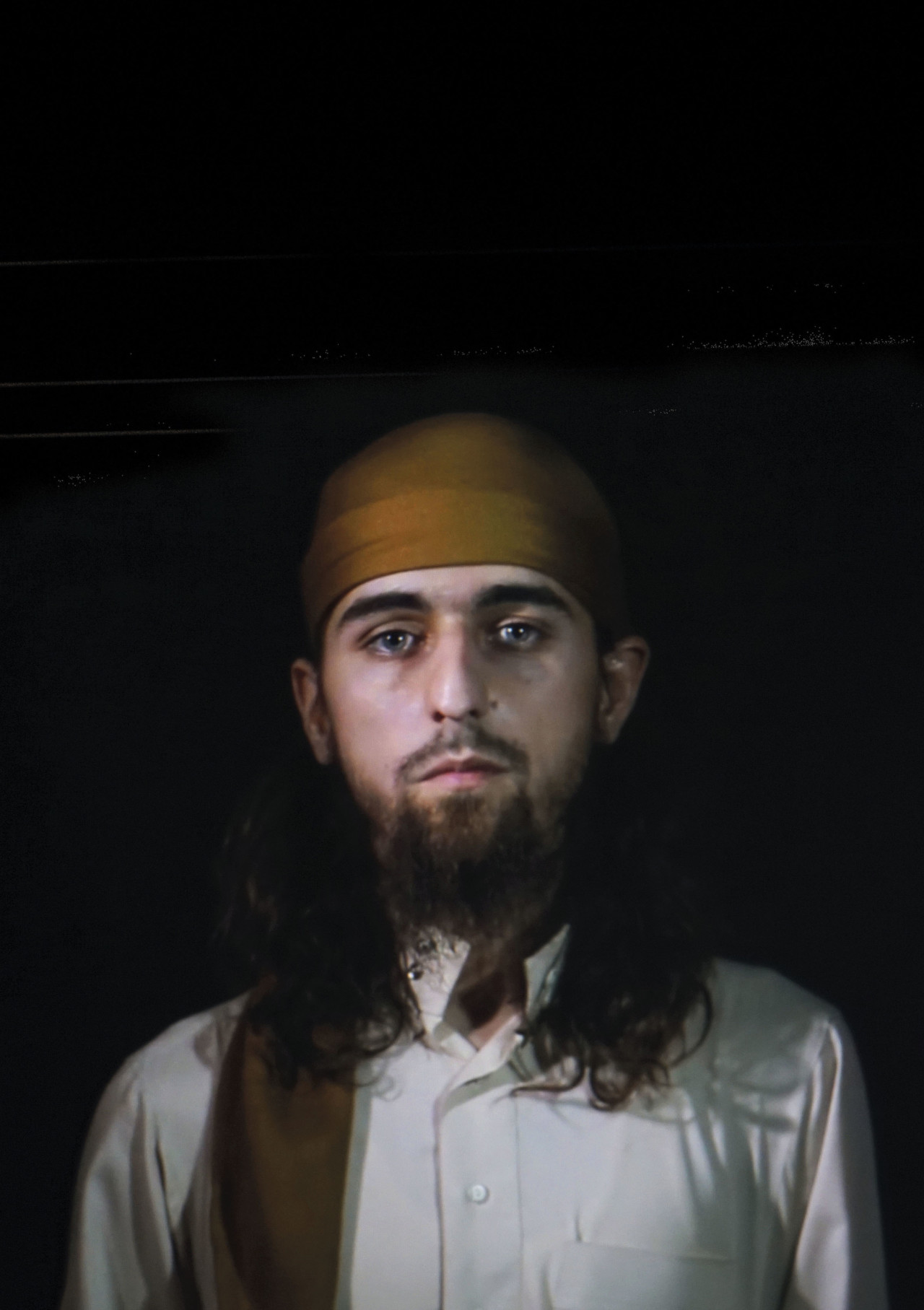

There are other lists of names in the book, such as the first 100 Iraqi civilian victims, shown opposite a devastating portrait of a traumatized man staring at the camera, his face covered in burns and heavy ointment, making it apparent that beyond these deaths there is a multitude of suffering.

There are pictures of American bombings, sectarian killings, Hussein’s mass murder, ISIS atrocities. The death is endless, the efforts at counting it insurmountable. This is tempered by images and stories that slow the count rate, that make the reader settle. A series of portraits of burns victims sees their gaze returned to the camera, the directness both an accusation and an invitation.

“The Little Serpent has left, and the great serpent has come,” reads a quote from Muqtada al-Sadr, the Shiite religious leader who came to prominence after Hussein’s fall. His face appears in numerous martyr posters photographed in the fighters section of a Najaf cemetery.

Death is ever-present, and it is iconized, celebrated, and mourned in varying forms. An image of a graveyard in the snow, the marble headstones carrying the names of American victims of the war, is strangely moving, its calmness broken by a quote from Abu Musab Al-Zarqawi, the head of Al-Qaeda in Iraq, that reads, “Perhaps God may cause something to happen in the hereafter.”

But there is also humanity in the book; a recognition that life is no cheaper in Iraq than it is on the streets of London, Paris or New York. An image shows Um Qusay, the woman who saved a large number of Shia, Christian, and Kurdish air cadets from massacre by ISIS in her hometown of Tikrit. She hid the cadets in the compound, dressed them as women and smuggled them out of the area as ISIS massacred around 1700 other cadets in the biggest single atrocity of the conflict. The exact number cannot be verified because there are insufficient DNA tests in cash-strapped Iraq to identify all the remains.

Other images show the attempts to carry on living amidst the mass of destruction. The buildings may be destroyed but the streets are still lined with racks of clothes as people try to get on with their daily lives. Kids still play in the street, only now they bounce off the top of cars destroyed by improvised explosive devices.

“I have tried to make visible the demands and political actions of the new generation of Iraqis who are fighting to break with past generations of violence.”

There is stillness in the book, and contemplation. A portrait of Salah Nazal, a cameraman who lost a leg in a targeted al-Qaeda bombing, is shown standing on a Mosul street, his eyes inviting you into his world. An image from 2019 shows Kurdish families displaced from Turkey seeking refuge in the relative safety of Iraqi Kurdistan, a region that he also portrays with a pastoral stillness; sheep grazing on the hillside, sun setting behind the rolling hills, but of course, there’s an old Kurdish graveyard in the foreground.

"“Sometimes I feel as fragile and insecure about what I'm doing as the first time I went on assignment."

-

This is part of Saman’s continuing questioning of what the photography of conflict can or should look like. It’s also a question of how to go beyond the ways conflict is framed by key participants in reporting, such as the military, politicians or the media, particularly in terms of embedding photographers.

“There’s the idea that, ‘We’ll give you access to this war, but we are only going to show you this one perspective.’ There are things that can happen that are out of their control that challenge those narratives. By creating a particular framework, those things become almost invisible. But there is never that level of control. Abu Ghraib is, I think, a good example of how things escape that control, no matter how much they try to shape the narrative with this system of trying to co-opt the journalist through this system of embeds.”

Saman shows one of the key Abu Ghraib images of Iraqi prisoners being tortured by American soldiers, the hooded man standing on a chair with electrodes attached. It’s an image from a set that Donald Rumsfeld and others believed should not be shown, because to show them would be ‘un-American.’ And here, un-American means going beyond the basic Hollywood plot of regime change, justice, redemption and how to one of chaos, murder and torture. It’s an un-American narrative because it’s one in which the US can make no claims to moral exceptionalism.

"A lot of times the picture is really elsewhere, and you are standing there pointing the camera in the wrong direction."

-

“Glad Tidings of Benevolence is about the basic fact of composing,” he explains. “About the act of when you photograph, you decide to leave certain things outside the picture. You go by what you know, or what you feel, but you are not right all the time. A lot of times the picture is really elsewhere, and you are standing there pointing the camera in the wrong direction.

“As a photographer, you are given a platform where you have power as a narrator. A lot of people get to see your images through the platform that you’re given. And I think that comes with a responsibility. I can’t say with all honesty that I understood that responsibility early on. I wish I had.

“I’m still a fast-paced editorial photographer, working on assignments. I’m trying to think through some of the theories around representation of conflict, the ideas of people like Judith Butler or Ariella Aïsha Azoulay, and to figure out ways to apply some of these ideas in my work.

“Sometimes I feel as fragile and insecure about what I’m doing as the first time I went on assignment. I’m 49 years old now, and I’ve been doing this for more than 20 years. But this fragility that I bring into what I’m doing is, in a sense, also what’s keeping me engaged and what’s keeping me questioning.”

There’s no final realization; no big ending to the war, the chaos, the destruction. And that’s deliberate. The book ends with a story by Saman’s wife, who was born in London into an Iraqi-Kurdish family, titled, ‘Is the fire still burning?’

It’s a title that refers both to a fire the family experienced recently in their Boston home, but also a reference to the overlay between the personal and the political, to the ongoing conflict in Iraq and a trauma that never ends neatly but still lies within, even when the story is supposedly complete. It’s a question she connects to her life, to her mother’s life, and to the life of her young daughter.

“Is the fire still burning?” she asks. “Resoundingly yes… The napalm in Halabja still burns. Mosul burns. Sinjar burns. Speicher burns. Kurdistan’s civil war smolders in plain sight.” But, she continues, those fires are part of her life. They are stories that are part of her life, of her daughter’s life, and they should never be forgotten. They need to be told. The question Saman is asking is, ‘How?’

Glad Tidings of Benevolence is now available on the Magnum Store.

The book has been longlisted for this year’s Kraszna-Krausz Photography Book Award. “Glad Tidings of Benevolence captures not just the chaos of the 2003 US invasion of Iraq itself, but the torrent of conflicting narratives that accompanied it, the ongoing political instability that it left in its wake, and the limits of documentary photography to report objectively on a war that, for most of those living in Iraq, is far from over,” writes Eugénie Shinkle, one of the three judges. Winners will be announced in early June.