Most People Were Silent

Revisiting Sim Chi Yin's 2017 Nobel Peace Prize commission to cover the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons (ICAN)

One is the only country to have tested nuclear weapons in the 21st century. The other is the first country to have tested and used them. North Korea and the United States are at two ends of the nuclear equation – but are locked in an ongoing and dangerous cycle of threats and counter-threats.

Magnum photographer Sim Chi Yin travelled 6,000 kilometers along the China / North Korea border and through six US states to create a project and series of diptychs reflecting on humankind’s experience with nuclear weapons, past and present. Here, following the 75th anniversary of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, we revisit Sim’s work accompanied by her own text, written in 2018.

In the pitch darkness, a single light was reflected in the shallow waters of the Tumen River. All that was visible on the far shore was a pair of giant portraits of North Korean founder Kim Il-sung and his son and successor Kim Jong-il. In the distance, beyond the barren hills, dogs barked, as if in rhythm.

Two weeks later, I stood on the desolate, dusty hills cocooning the United States nuclear test site in Nevada, listening to the calm, eerie ring of silence. I seemed to hear those same dogs. I had come to find traces of humans’ encounter with nuclear bombs—the only weapon that can destroy humanity in a single blow. In October 2017, I drove along the quiet, empty border between China and North Korea, photographing across the two rivers and one mountain that divides them. I searched out locations closest to North Korea’s known nuclear test sites, missile-manufacturing facilities and munitions bases.

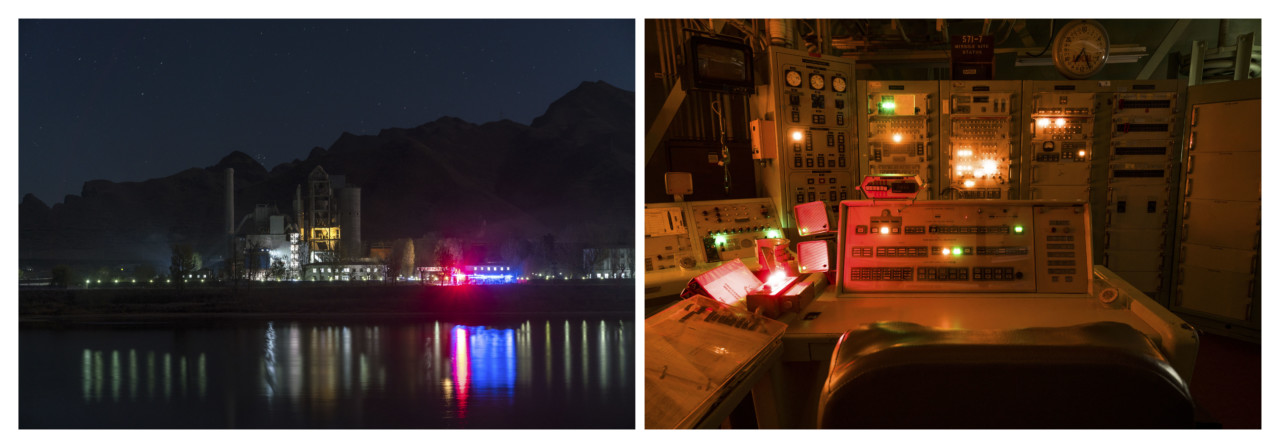

A fortnight later, I travelled through equally quiet stretches of the western United States to find nuclear sites, from snowy North Dakota, where an all-seeing pyramidal anti-missile radar complex stands, to the white heat of the moon-like, cratered test site in Nevada’s desert. I climbed into missile silos, crawled out of bomber escape hatches, came face to face with warheads and wandered around command and control centres used during the Cold War. I was looking for parallels—visual, historical, factual, symbolic—between these landscapes. North Korea is the only country to have tested nuclear weapons in the 21st century. The United States of America is the first country to have tested and the only country to have used them, in 1945. In 2017, when I started this project (on a commission for the Nobel Peace Prize), the two countries were locked in a rhetorical war attacking each other, with President Donald Trump taking swipes at North Korean leader Kim Jong-un as ‘Little Rocket Man’, while his counterpart called him a ‘gangster fond of playing with fire’. There has been a dramatic diplomatic about-face in the past several months. The two leaders had an unprecedented summit in Singapore on 12 June where Kim made a broad commitment to ‘work toward denuclearisation of the Korean Peninsula’. So far, though, no details exist and the deal remains shadowy.

"For most of us, all this takes place in the abstract—on Twitter, in the news or in theory. I wanted to see what the actual nuclear infrastructure looks like. I wanted to understand how these weapons work, what the command chain was, how we used them and might do so again..."

-

For most of us, all this takes place in the abstract—on Twitter, in the news or in theory. I wanted to see what the actual nuclear infrastructure looks like. I wanted to understand how these weapons work, what the command chain was, how we used them and might do so again. I wondered about morality and other questions: What do we make of the repeated calls to ban these weapons on the one hand, or the arguments that we need them for deterrence? On my journey, I met people from both ends of the spectrum. Some view the weapons with awe and respect, such as Yvonne Morris, director at the Titan Missile Museum in Arizona, who spoke quietly as she looked down at the massive, sleek missile illuminated by flood lamps, newly installed in its silo. This was the nuclear-tipped weapon she had commanded in the 1980s. She said: ‘I would have had no trouble following the launch command, if it had come to that, because it would have meant that the US was under attack’.

I also met educator Joseph Brehm, whose father was an American World War II bomber pilot possibly saved from having to fight in Japan because the atomic bombs that destroyed Hiroshima and Nagasaki helped bring the war to a quick end. The younger Brehm grew up believing in nuclear weapons but now calls for disarmament: ‘I love technology, love the wow factor: Oh my God look what we created. But then you have to take a step back and realise, what did we create? Because it literally is the sword that could slay humanity’. With each site I visited, I felt the beauty and the weight of these landscapes and quiet machines. I had studied Cold War history at university, reading books and texts about that dangerous era. But suddenly these events came alive in the metres-thick concrete blast doors of the missile silos and in the rusty complexes far below ground.

North Korea’s nuclear ambitions and—more recently—pledges to denuclearise can be gauged only through satellite images, seismic tests, propaganda pictures and official pronouncements. That forced me to look through barbed wire fences, mountains and villages, metaphorically trying to see the missile sites and the Punggyi-ri nuclear test site where Pyongyang has conducted six nuclear tests since 2006. The latest and largest test had taken place just a month before my journey, causing buildings to shake, knives to rattle in kitchens and schools to evacuate in neighbouring Chinese towns.

In some ways those landscapes were from a different era: farmers pushing carts at a gentle speed, single-storey houses with stacks of corn at the front, steam-powered tractors, workers bicycling back to factories after lunch hour, and factory chimneys with wisps of smoke rising into the night sky. But the sense of tension was palpable: the regular guard posts on the North Korean and the Chinese side, the constant checkpoints and border police forbidding photography.

In the United States, I was welcome to look at decommissioned facilities preserved for tours and education, and sites that had been abandoned after serving their purpose. Only at the 3,500 square kilometre Nevada National Security Site—an active site—was I kept outside the fence. Over 900 nuclear weapons tests were done here between 1951 and 1992, creating a series of giant craters in the ground resembling a moonscape visible in satellite images. It was seeing an archival United States military photograph of the largest of these—the Sedan crater—that first led me to think I could create a series of ‘anonymous’ landscapes of these two countries, images that when placed side by side might let us suspend our sense of place and become reflective.

"Elements of what I saw in both places intersected in my mind. Some of the parallels were clear as soon as I shot the second picture in a pair; others I discovered in the editing process. Across both countries there were striking similarities in the landscapes—both natural and man-made..."

-

Elements of what I saw in both places intersected in my mind. Some of the parallels were clear as soon as I shot the second picture in a pair; others I discovered in the editing process. Across both countries there were striking similarities in the landscapes—both natural and man-made. Perhaps, as Natalie Luvera, a curator at the National Atomic Testing Museum in Nevada, put it: ‘We haven’t learnt from history. What the US did in the past is being repeated right now in North Korea’.

Trump and Kim both portray themselves as having written a new chapter in history, with handshakes and smiles at the Singapore summit in 2018. Soon after, North Korea invited international journalists to witness what it said was the demolition of the Punggye-ri nuclear test site. No experts were on hand to verify what was destroyed. On the United States side, Trump unveiled changes to the country’s nuclear posture early in 2018, increasing the country’s arsenal and developing more ‘usable’ nuclear warheads.

In recent weeks, academics and US intelligence agencies have been reporting that, pledges notwithstanding, North Korea has increased its production of fuel for nuclear weapons at multiple secret sites and has made infrastructure improvements at Yongbyon—its major declared nuclear facility. US officials say they are ‘watching closely’. The rest of us continue to try to see, from outside the fence.

Sim Chi Yin New Mexico, July 2018