One Influential Image: David Hurn

David Hurn recalls stumbling upon the image which moved him to decide to become a photographer

David Hurn is well-known for his work within Magnum documenting empathetic stories of ordinary life. A photographer within a collective initially established based on its work on conflict and its effects, Hurn distinguished his practice through his insights on human societies in their quieter and more joyful moments: from nimble portraits of celebrities, to studies of life in Arizona and California, to his multi-decade-long dedication to Wales and its disappearing traditional cultures.

In this text, Hurn shares the story behind a single image that had a profound effect on his life, leading him down his path into photography, and shaping his particular approach to his work.

I am extremely dyslexic. When I was at school there was no such word – you were thick. I actually wished to be either an archaeologist or a veterinary. For the latter you needed qualifications in Latin to enter university. I went straight from school into the army to do 18 months of, what was then compulsory, ’National Service’. I have always had a good organisational mind and have an instinct for essentials – I was soon offered a place in the Royal Military Academy Sandhurst. My life was mapped out for me – an ‘officer and a gentleman’. I think I would have made a good army officer.

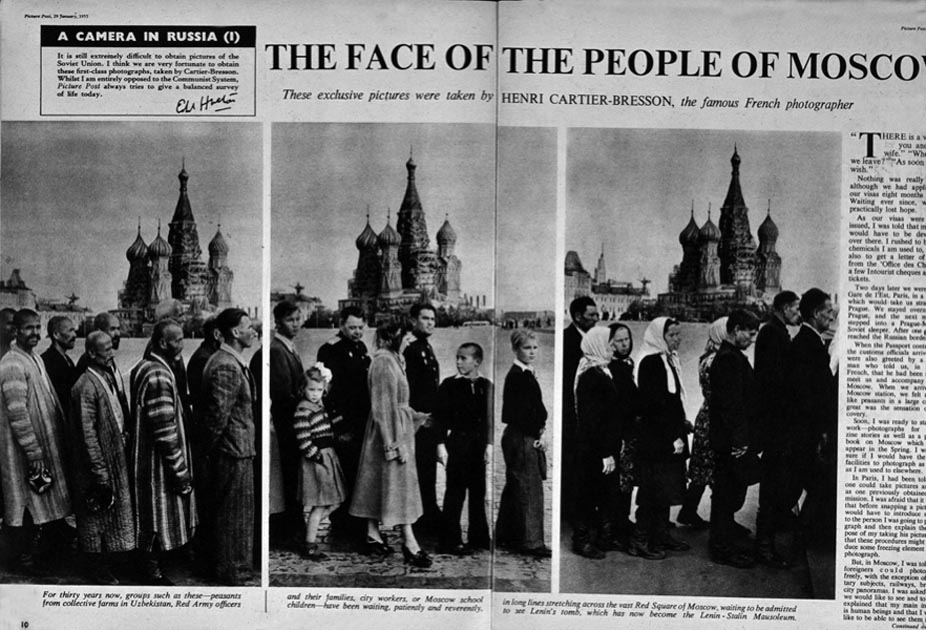

One day at the military academy, in the officers’ mess, I started to cry — not a normal occurrence. It occurred on seeing a photograph in Picture Post, the foremost serious picture magazine of the period. The photograph was part of a photo essay, ’The Face of the people of Moscow’, which was split over four editions of the weekly magazine. January 29, February 5, February 12, and February 19, 1955. A total of 19 pages of pictures.

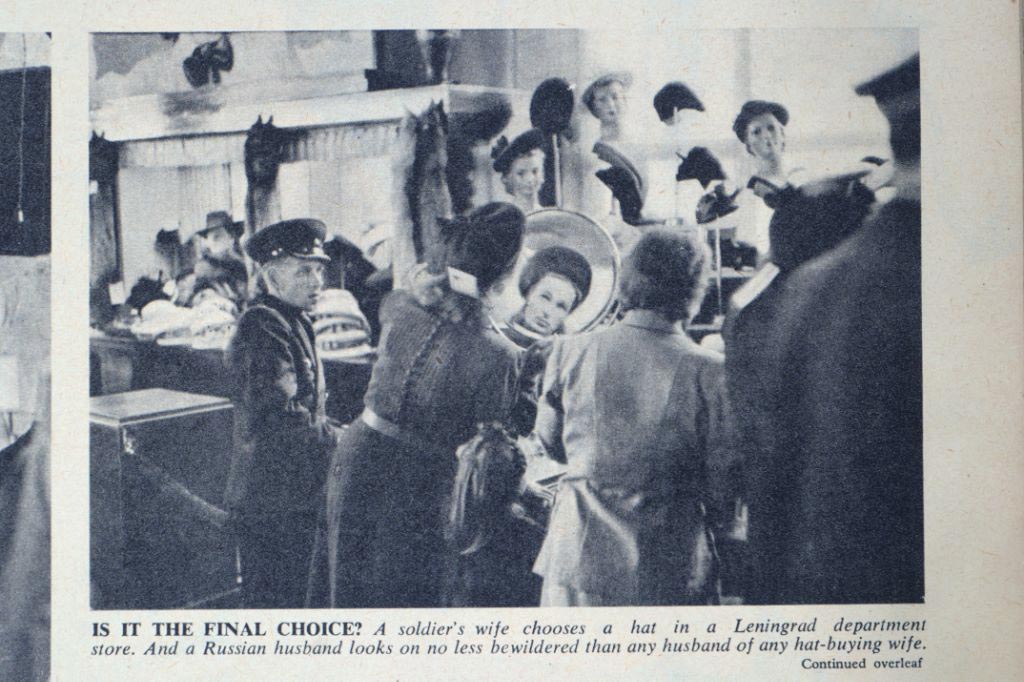

The picture in question, was in the February 12 issue. It showed an image with the caption, ‘A soldiers wife chooses a hat in a Leningrad department store. And a Russian husband (an army officer) looks on no less bewildered than any husband of any hat-buying wife.’

My father had been away from the UK during most of the Second World War. I have no memory of him during this time. When he returned, one of the first things he did was to take my mother, with me in tow, to buy her a hat in Howells, a department store in our home town of Cardiff, South Wales. It was the first time I had seen a demonstration of the deep love between my father and my mother. The picture in the magazine brought a greatly enhanced memory of the occasion.

On reflection soon after, I realised the photographed affected me deeply in three main ways: it brought about deep emotion, it brought back memory, and it counteracted propaganda (at Sandhurst all Russians were ‘bad’ people’).

I realised that to be involved in these three possibilities would be very worthwhile. I immediately decided that what I really wanted to be was a photographer dealing with the mundane, the ordinary. I have been taking the same picture ever since. The photo essay was by a photographer, whom of course I had never heard of: Henri Cartier-Bresson.