Philip Jones Griffiths in His Own Words

We present photographer Philip Jones Griffiths' personal thoughts on his diligent documentation of humanity.

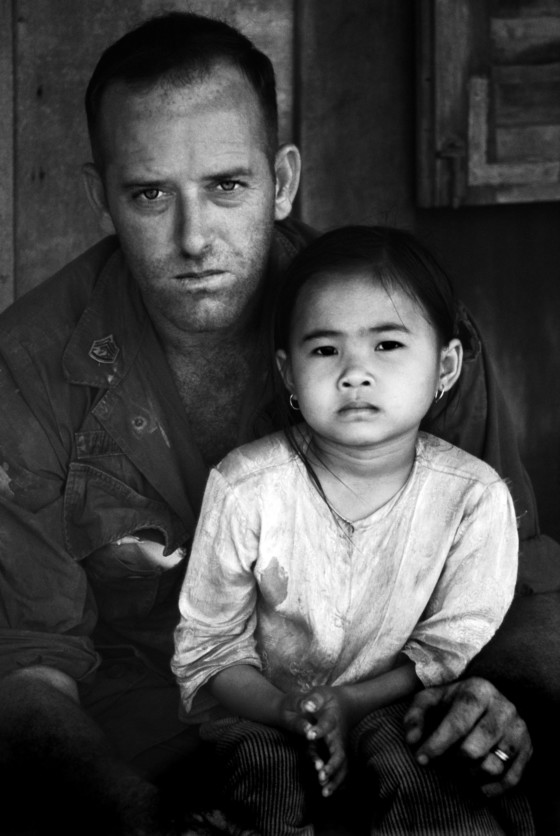

“Not since Goya has anyone portrayed war like Philip Jones Griffiths,” said Magnum co-founder Henri Cartier-Bresson of the Magnum president. However, the photographer’s repertoire captures a far wider portrait of the human condition than its penchant for violence (which he did document in its extremes during the wars in Vietnam and Algeria). His portrayal of ordinary life in Great Britain, the reality of living through the Troubles in Northern Ireland, and global communities with radically different ways of life to that one he’d grown up with in his native Wales, are presented with detailed texts and captions that reveal his astute observations about the mechanics of war, the Western psyche and collisions of ideology.

His insights would, on occasion, appear prophetic. His book Vietnam Inc. (1971), which he dedicated to fallen fellow photographers, was published in the same year that the Washington Post famously broke ground by publishing the Pentagon’s secret papers. The leak exposed high-level doubts about military decision making in Vietnam and included details of government concerns that the war was unwinnable at a time when they were being publicly positive about it’s prospects. Philip Jones Griffiths’ own writing on the situation revealed insights that seemed to echo much of what the U.S. government seemed to be saying in private.

"The Camera requires one to be there – a photographer is denied the luxury of philosophizing from afar."

- Philip Jones Griffiths

A deeply felt sense of justice and affinity with those whose lives were torn apart brought Griffiths back to Vietnam to trace the devastating effects of the defoliant known as ‘Agent Orange’. His experiences of war afforded him a unique perspective on the Troubles in Northern Ireland. Jarring, darkly humourous images showed British Soldiers dressed in full military gear stalking neatly manicured gardens, and lurking next to the village corner shop. His opinions became clear through his detailed, acerbic captions: “The incongruities of daily life in the urban war zone. For years, the people of Northern Ireland lived in a strange and strained symbiosis with the occupying British army,” he wrote.

The retrospective book Dark Odyssey (1996) took stock of Griffiths’s 40-years of photography, with career highlights published along with his own reflective writing. Here, we present some of the photographer’s words, where he ruminates on his practice, and the world he assiduously documented.

"I took delight in being the silent observer in rowdy crowds, the all-too-visible invisible man"

- Philip Jones Griffiths

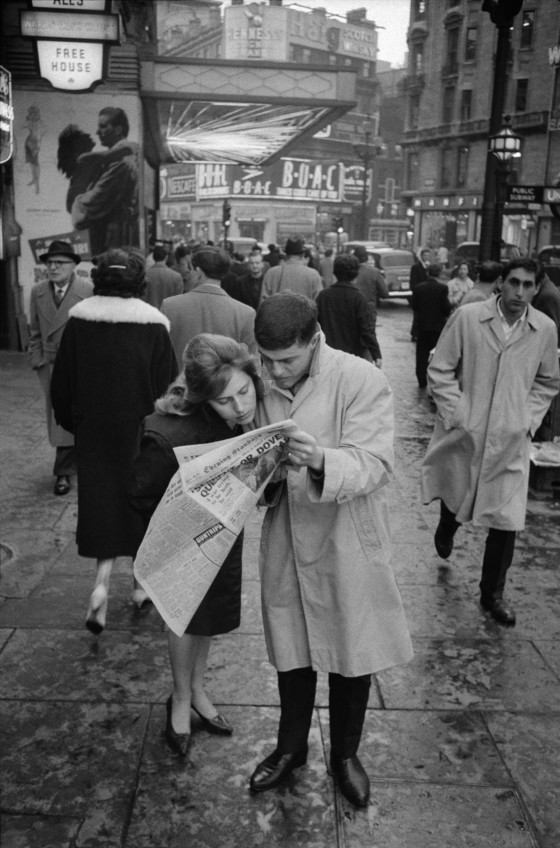

On his early inspiration in Wales

“I discovered photography among various youthful distractions. As I immersed myself in the subject, I came across a statement by Henri Cartier-Bresson, explaining that with a camera the discovery of the external world simultaneously reveals the internal world. I found this prospect electrifying: it had to be key to the meaning of life!

Wales has a puritanical culture and heritage of strict morality. While I had no difficulty rejecting mandates hurled from the pulpit, in ensuing arguments I found myself embracing the idea that life should have a purpose. I now felt lucky to have discovered one.

Revelling in my new-found calling, I set out to explore my own country. With my prophetically named Agiflex camera around my neck and Camus’s The Stranger in my pocket, I took delight in being the silent observer in rowdy crowds, the all-too-visible invisible man.”

On Photographing Conflict

“In war, truth is almost inevitably the first casualty. Lies are as indispensable as ammunition – often they are the ammunition. My camera has given me opportunities to witness the deceit implicit in conflicts, and my goal is to see through the deceptions. The Camera requires one to be there – a photographer is denied the luxury of philosophizing from afar.

There are photographers who are still hammering home simplistic maxims about “man’s inhumanity to man.” This affords little insight into the subject. What we need is to understand the reasons why men set out to kill one another – a good place to start would be the realm of economics. Then, perhaps we will be able to find another way to solve our differences.”

On Religion and Morality

“It has always been easy to find connections between immoral behaviours and religion. The Christian church claims a monopoly on virtue, yet its role in the genocide of the inhabitants of the Americas required a suspension of moral values. I have noticed that most societies have a highly developed code of morality, quite independent of any religion.True, the code is often appropriated by or credited to a religion – if the mountain of gorillas of Rwanda were a notch of two “higher” on the evolutionary tree, the American Republican party would no doubt attribute their harmonious lifestyle to the success of Christian values.

In my youth, it was the debate over nuclear weapons that highlighted the gulf between religion and morality. The opposition to government policy was essentially secular. The prospect of instant death – we were assured we would have four minutes to say our good-byes before vaporization – concentrated the public mind on no answer other than the lame suggestion that is we were all the die in a man-made hellfire on earth, then we’d get preferential treatment on reaching the pearly gates.”

On the Vietnam War

“The war in Southeast Asia revealed the true nature of American foreign policy as it had never been seen before. Fore more than ten years the wealthiest and most powerful nation on earth tried everything short of nuclear weapons to defeat a nationalist revolutionary movement in a small nation of poor rice farmers. And they failed. Despite the slaughter, the people triumphed. America had the smart bombs but the Vietnamese had the smart minds. The battle was between technology and human beings, and the human beings won.

Being British, and a photographer, I had a privileged overview of the contest. I spent five years immersed in Vietnam trying to make sense of what was going on. All that was needed was a cool head, a sharp eye and a modicum of humanity to qualify as a serious observer. My book Vietnam Inc. examined every aspect of the war and, I hope, helped illuminate the subject.

At times the Vietnam War, like all wars, had the drama of the Forces of Darkness murdering the Innocents. The task, of course, was to see beyond the obvious. All wars produce the familiar iconic images of horror, which do little to further anyone’s understanding of a particular conflict. My purpose was to understand the nature of the war, and reveal the truth about it, with photographs providing the visual proof. The photographs are the evidence.”

Browse the curation of Philip Jones Griffiths fine prints on the Magnum shop here.