Photography and the Art of Looking

Darran Anderson explores the complex dynamics of the gaze between artist, subject, photographer and viewer

Photography is the art of looking. This seems a neutral term but it is, in fact, weighted. Who, how and why all matter, especially in terms of dynamics. Though we often read of ‘the gaze’ in academic works, it is rarely objective or singular. One person’s honest gaze is another’s intimidating voyeurism. And while a muse may be objectified, they too gaze back. Photography may be the capturing of a moment of truth but it is never definitive. Every scene can be viewed from multiple angles and perspectives. What was happening out of shot? What was happening before and after?

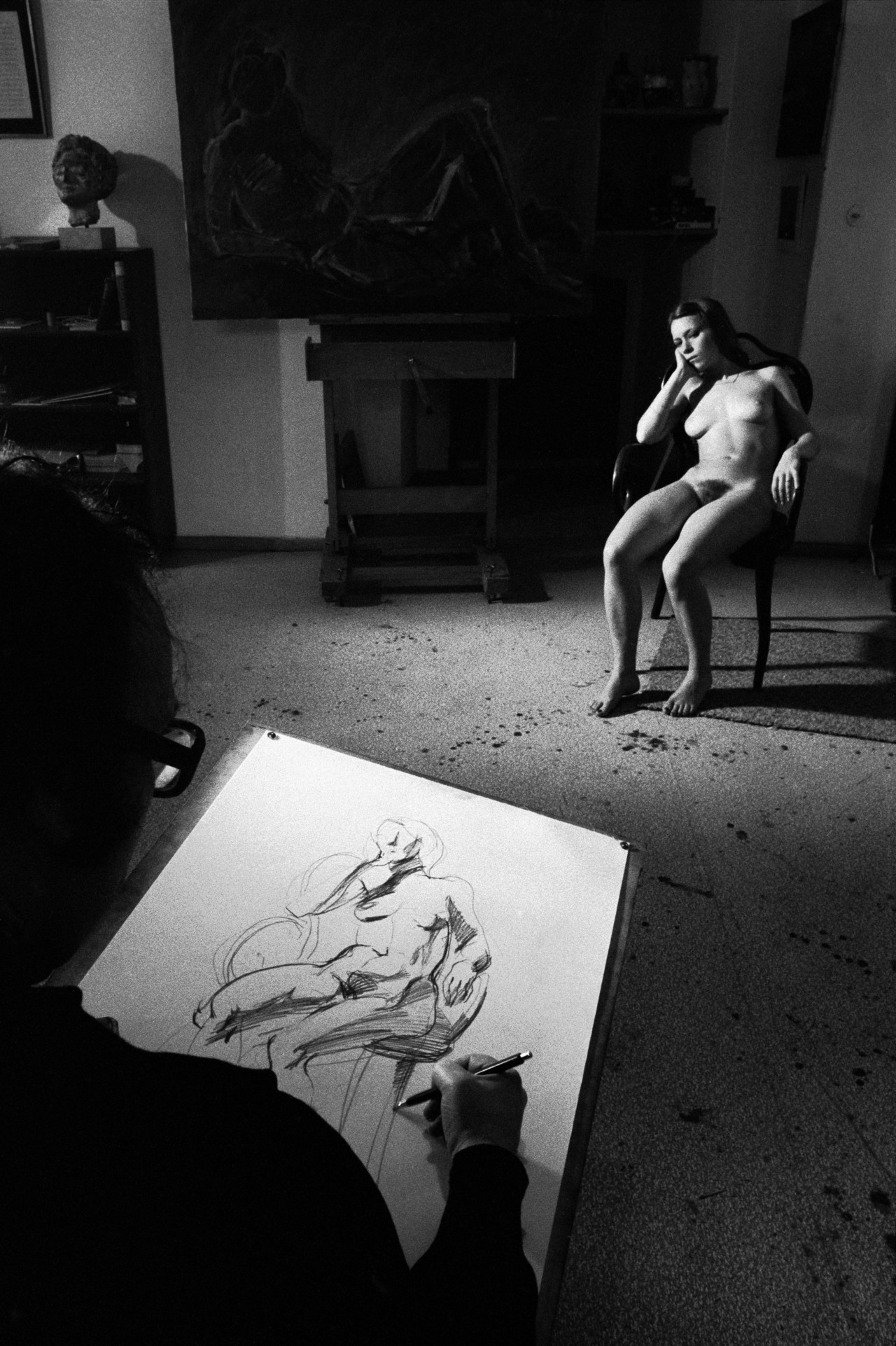

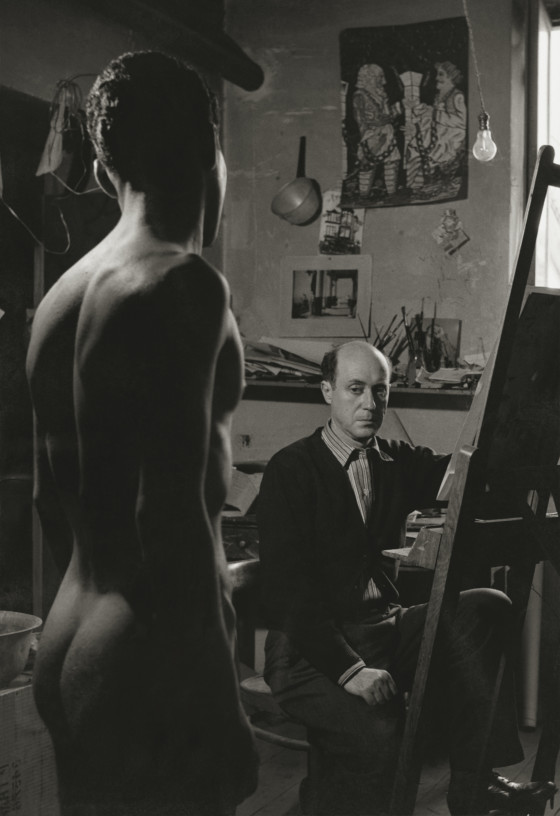

The following photographs, from Magnum’s archives, remind us of this multiplicity, in both photography and art, another medium that aims at communicating or capturing a truth. We are looking at someone looking at someone looking at someone who is looking back. The photographer, we might feel is an interloper, gazing over the shoulder of the artist in Erich Lessing’s image but we too are interlopers as external viewers. The sense of dislocation or voyeurism is deepened by the knowledge that we are gazing at a scene that is long-gone, with figures who may well be dead. All photography is temporal as well as spatial; a moment trapped in amber.

Traditionally, the gaze has often been that of the older male artist studying and portraying a younger woman. The muse is simultaneously an elevating and constraining role. The subject may be painted as a goddess but in the manner of a bowl of fruit. Can we look at such scenes with a sense of innocence anymore? Perhaps not, possibly because it never entirely possessed innocence. We often gaze on what we desire or are repulsed by. Certainly, judgement is rarely far away. “You painted a naked woman because you enjoyed looking at her,” John Berger notes in Ways of Seeing, “put a mirror in her hand and you called the painting ‘Vanity,’ thus morally condemning the woman whose nakedness you had depicted for you own pleasure.” While truthful, this point can, of course, be overstated. Desire can also be the desire to be desired and the individual portrayed possesses agency, even if the power dynamics are heavily lop-sided (when artists would employ sex-workers, for example, to sit for them).

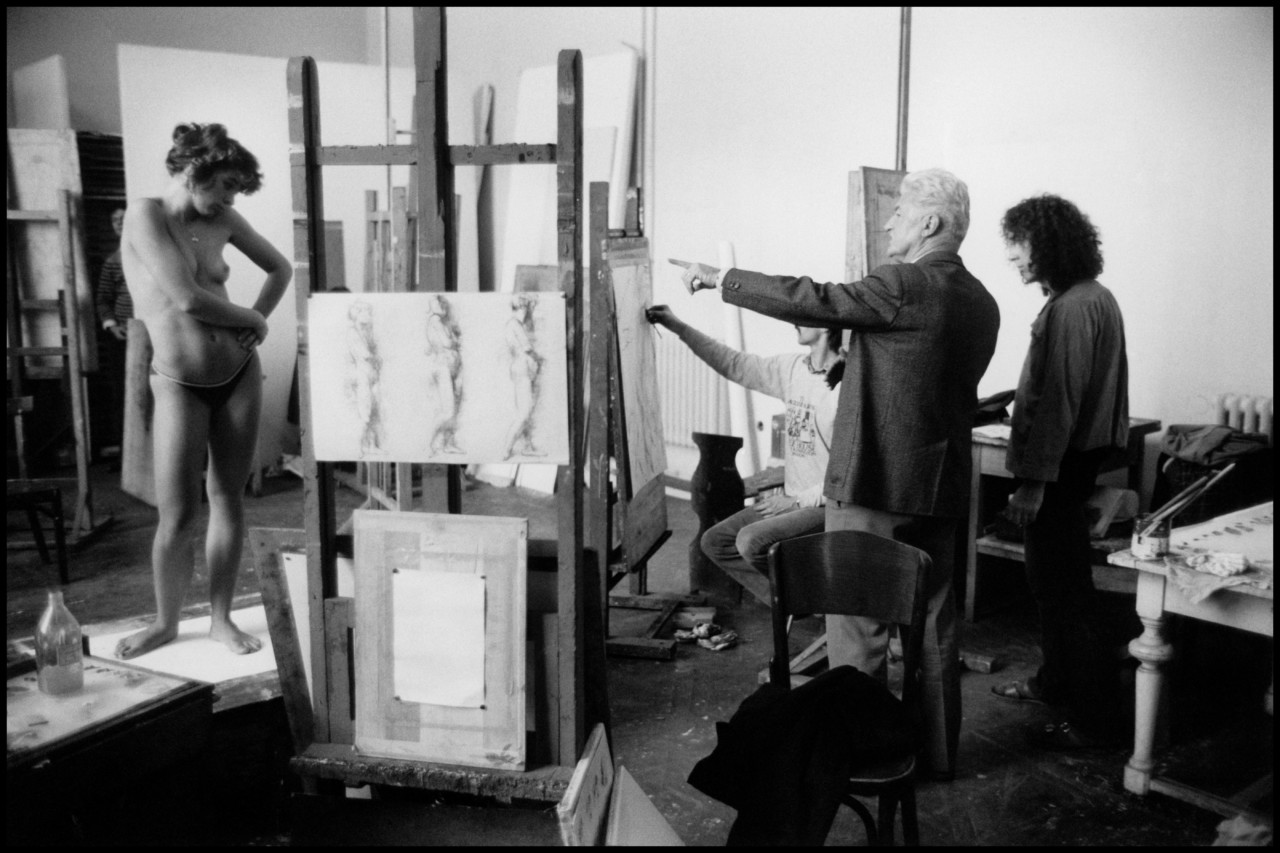

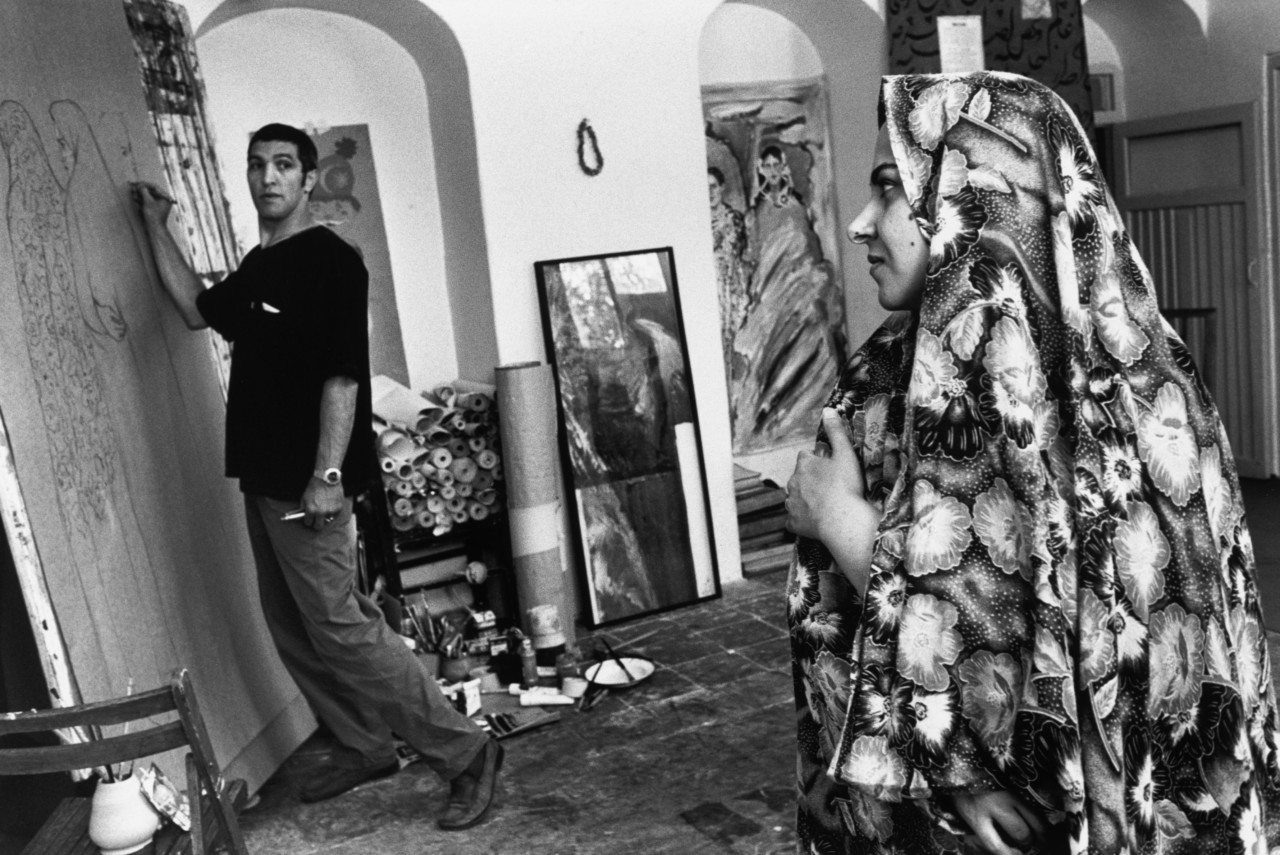

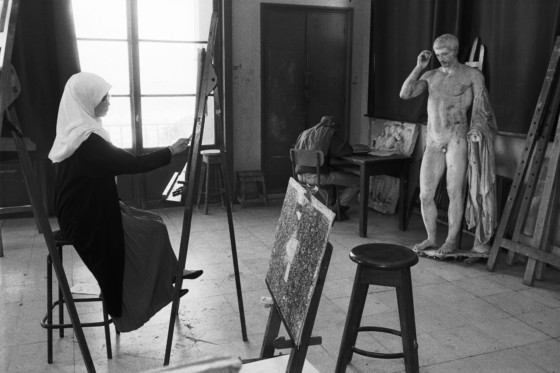

In Abbas‘ photograph from Tehran in 2001, we see the artist-model scene with the perspective shifted. There is a vibrancy here that transcends the typical dichotomy. Khosrow Hassanzadeh is painting his wife Ashraf. The photograph is taken next to her. Crucially, she can see her portrait unfolding and the dynamic is less oppositional. In his photograph from the Beaux-Arts School in Paris, 1981, Abbas demonstrates how difficult it is to faithfully depict the human form. There is something about the model, between the pale austere statues, that seems full and glowing with life. It takes a rare genius like Bernini to fully replicate something as simple as the human touch.

"You do not need to know that he depicted her almost a hundred times, that they fled the Nazis together, that he drew her on his deathbed, to sense the connection in her stare, open, affectionate and penetrating"

- Darran Anderson on Henri Matisse and Lydia Delectorskaya

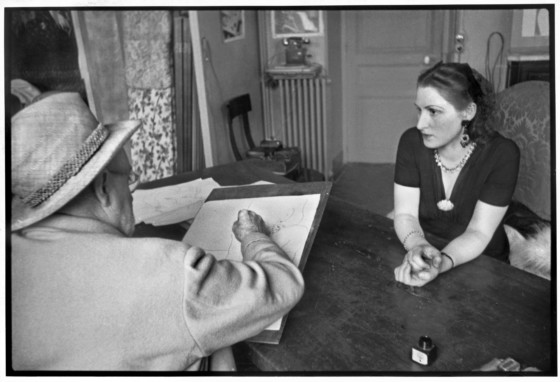

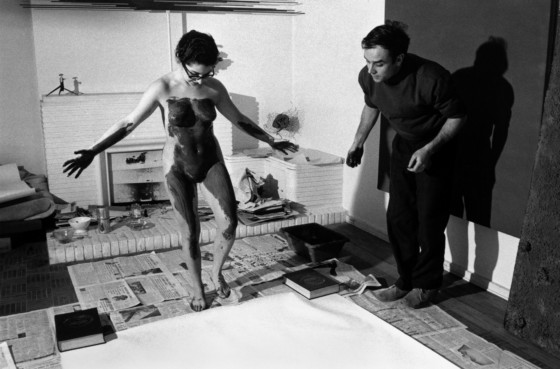

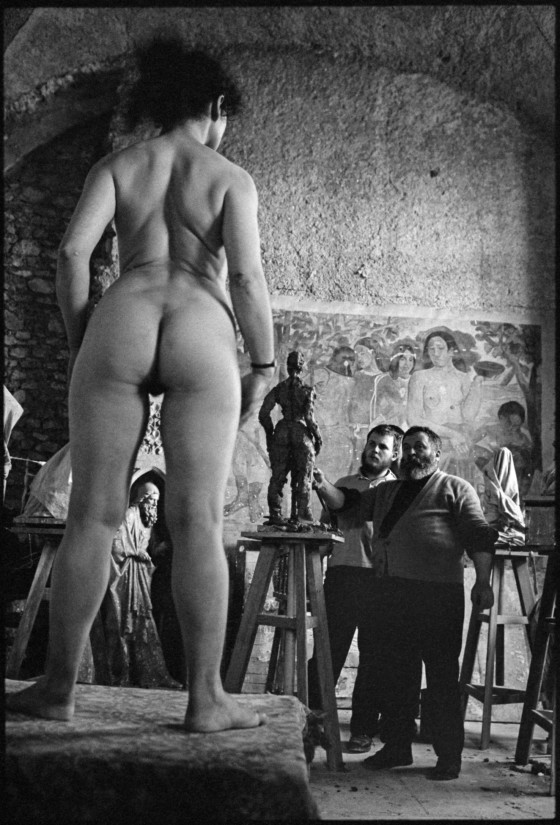

The photographs act as reflexive portraits of the artists themselves. These can be commanding presences like the sculptor Etienne Martin in Martine Franck’s shots from 1966. They can be dynamic and performative like Yves Klein, guiding a model through ‘body art painting’ in Rene Burri’s photograph. In Cartier-Bresson’s studies of Matisse, the artist is approached subtly; his character inferred from his stature and clothes. Just as resonant and implicit here is the deep and complex relationship between Matisse and his model Lydia Délectorskaya. You do not need to know that he depicted her almost a hundred times, that they fled the Nazis together, that he drew her on his deathbed, to sense the connection in her stare, open, affectionate and penetrating.

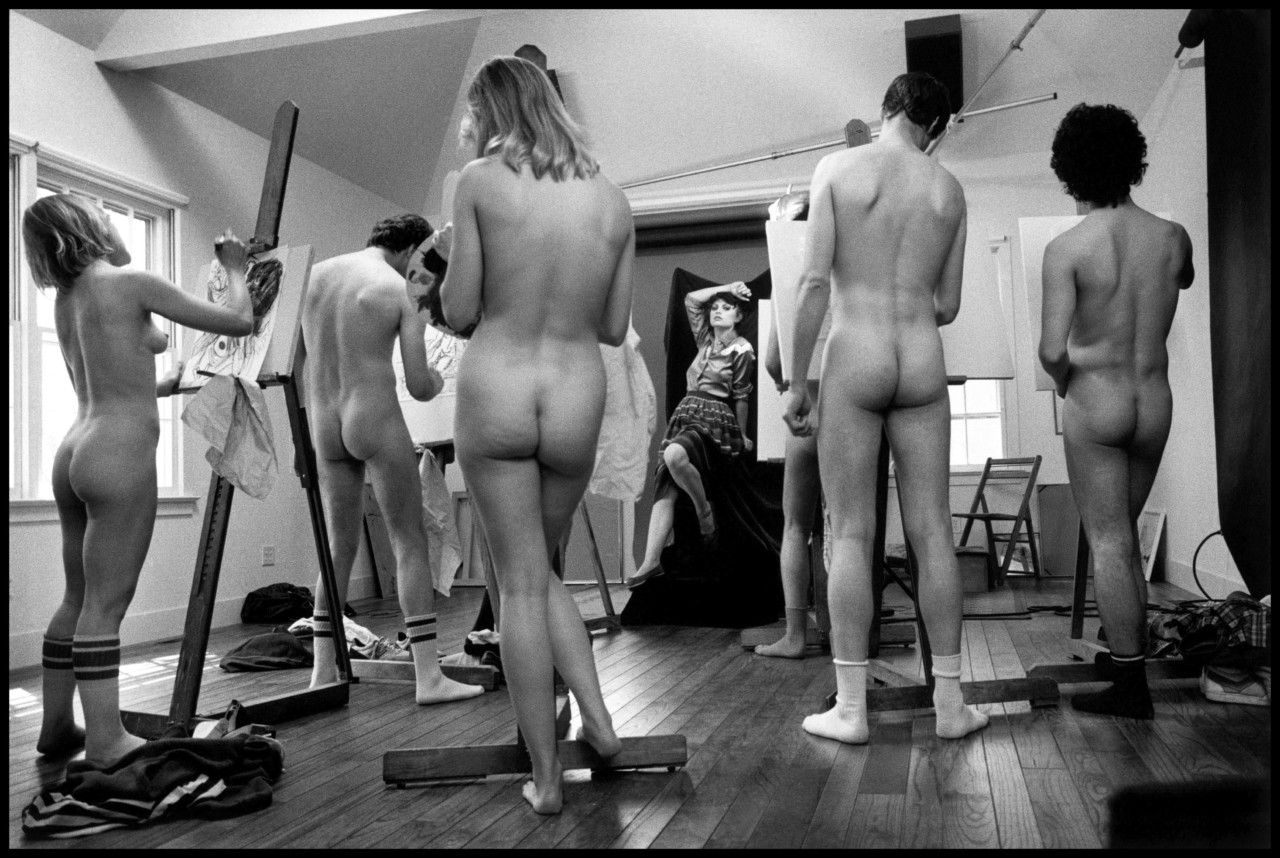

At times, the photographs act as portraits of the photographer. Herbert List’s image of the painter Yannis Tsarouchis glancing at a particular part of the model’s anatomy is mischievous. The naked artists and the clothed model, in Elliott Erwitt’s 1983 image, is an irreverent reversal, while Eve Arnold’s ‘Chongking Art Class, 1979’ (at the top of this page) is a strikingly inventive, almost post-modern, example of the multiplicity of perspectives.

"At the heart of these images we find not just the intense study of who we are but the artifice involved"

- Darran Anderson

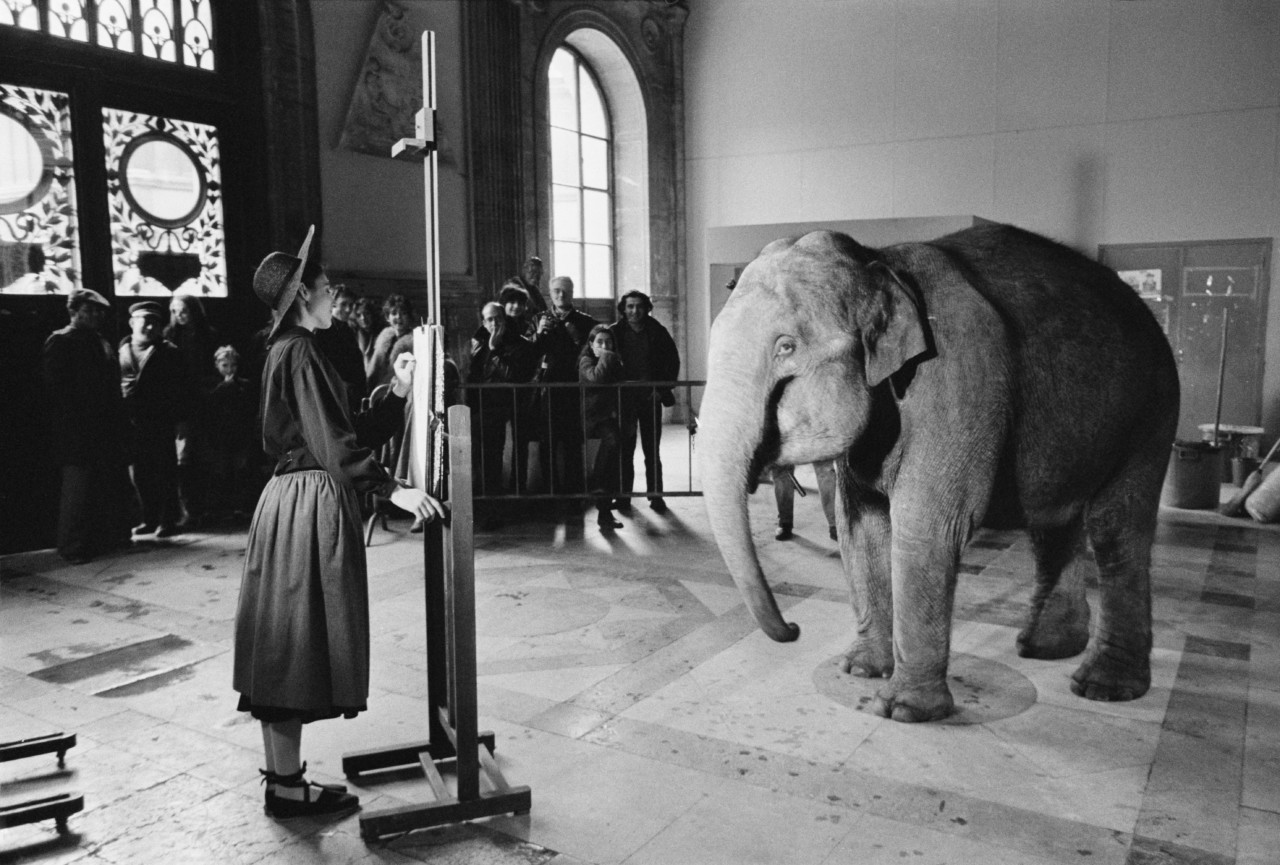

At the heart of these images we find not just the intense study of who we are but the artifice involved (as we see in Rene Burri’s image of a fashion model posing as an artist, in front of an elephant). In real-life, we are presented with the naked form, or present ourselves, only really in sexual or medical settings. The artist’s studio is a curious antechamber, one step removed from the day-to-day. The artist aims for naturalism but with contrived poses in a remarkably artificial environment. Yet there is something about this, thae absence from the everyday, that gives it power. In a world where everyone is now snapping everything with camera-phones, the idea of diligently drawing or painting someone has a renewed power. Its very redundancy has revived it. We are, for example, creatures of motion, as suggested in Thomas Hoepker’s image of the Korean National Academy of Arts modelling class. The unnatural element of stillness in life modelling does not remove this quality so much as amplify it. Every gesture suddenly demands attention, much in the way that John Cage’s 4′33″ is not about silence so much as the impossibility of silence or how in Chris Marker’s film La Jetée the sudden unexpected movement of the female character becomes incredibly powerful and beautiful because it is so fleeting among otherwise still images.

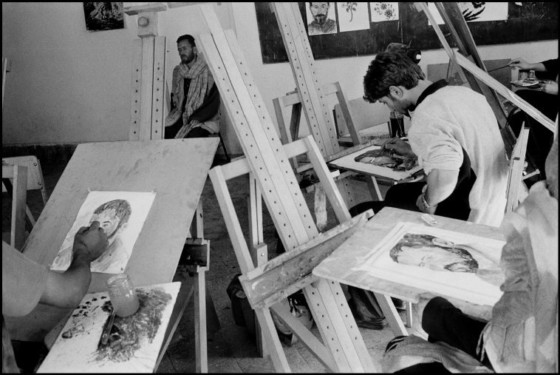

The study of the human form, whether between artists or anatomists, is ancient and innate; as shown by the child’s stick drawings in Abbas’ photograph at the home of Mario Cravo Neto. We are curious creatures in more ways than one. Inadvertently, these portraits, and the gazes within rooms or groups of people, are also portraits of the wider societies, whether it’s Eve Arnold’s image of Chinese advertising apprentices depicting the body or Martin Parr’s tourists in Paris awaiting portraits. They tell us stories of tradition and change, shame and subversion, exploitation and expression. In Algeria, Abbas shows an artist painting from a naked statue, given the prohibition of naked live models. In Afghanistan, he captures students at Kabul University finally being able to paint the human face, having been forbidden to do so under the earlier Taliban regime. The urge to depict one other, and to see ourselves depicted, is as natural and inextinguishable as gazing at each other.

"There is little doubt that we are performers and watchers but it’s also telling that we reveal who we are when we think no-one is looking."

- Darran Anderson

In Burt Glinn’s photograph of the painter Casey Van Duren and the model Virginia Campbell-Buller, we have an image that is casual and natural. This is how we act, outside of poses and prohibitions. There is little doubt that we are performers and watchers but it’s also telling that we reveal who we are when we think no-one is looking.