Photography and Cinema

Exploring the interplay between the disciplines of photography and cinema

Magnum Photographers

Magnum’s love affair with cinema began very literally; Magnum co-founder Robert Capa’s love affair with Swedish actress Ingrid Bergman led to the first ‘on set’ Magnum shoot, as Capa talked his way into shooting behind the scenes of her film Notorious in 1946. This was followed by further visitations to film sets by Magnum photographers. One notable example was the 1961 film The Misfits, directed by John Houston and starring Marilyn Monroe, Clark Gable and Montgomery Clift. As part of the promotional strategy for the film, the Magnum agency was given exclusive access to the production. Nine of its best-known photographers – Eve Arnold, Cornell Capa, Henri Cartier-Bresson, Bruce Davidson, Elliot Erwitt, Ernst Haas, Erich Hartmann, Inge Morath, and Dennis Stock – covered events both on and off the set.

The relationship between Magnum photographers and cinema has been one of mutual give and take, and nowhere better is this demonstrated than the way cinematographers and directors have looked to the work of photographers for inspiration, and photographers, too, have taken inspiration from film. Magnum photographer Harry Gruyaert took part in a discussion about this unique relationship at the Barbican in London. Here, we explore the relationship between the photography of Magnum photographers and cinema, looking at what one has to gain from the other, and the enhanced perspective that comes when they combine.

Photographers Inspired by Cinema

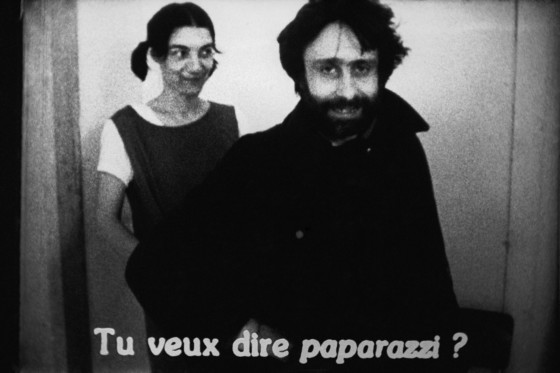

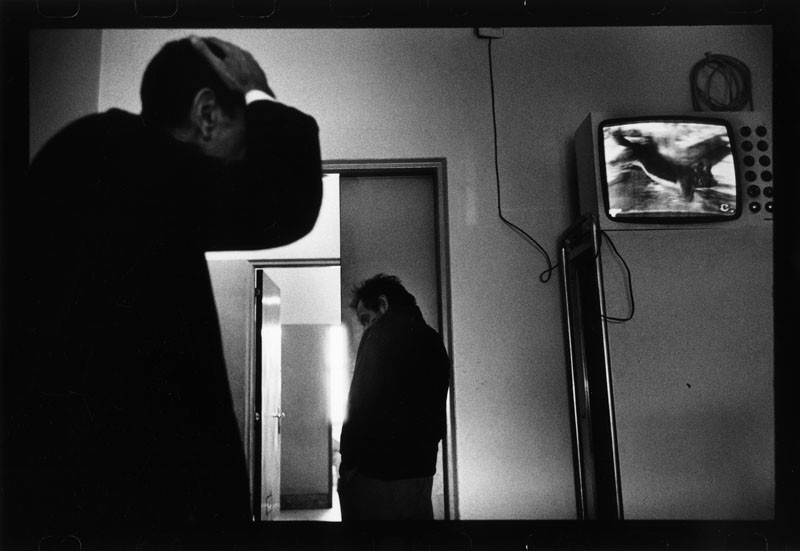

Whilst traditional photojournalists see their role as that of a reporter of events as they happen, there’s another type of photographer who takes an approach to their practice that has more in common with an artist. “I feel closer to painting and the cinema than I do to journalism,” says Magnum’s Harry Gruyaert. Known for his cinematic employment of light and color, and a fascination with the medium of cinema and television (see his TV Stories for a study of 1970s media as viewed through the prism of the television set), Gruyaert’s love of cinema saw him experimenting in the medium himself, making several short films early in his career. “If the quality of digital cameras that exist right now were available back then I definitely would have done more movies,” he said, talking at the Magnum Photos Now Barbican event.

Gruyart’s practice has been, he says, heavily influenced by the atmospheric work of Italian director Michelangelo Antonioni, most well known for cult film Blow Up (1966). Harry Gruyaert produced a film that drew comparisons between his own photography and moving image works and Antonioni’s films, which was featured in his solo show Variations Under Inspiration.

"I feel closer to painting and the cinema than I do to journalism"

- Harry Gruyaert

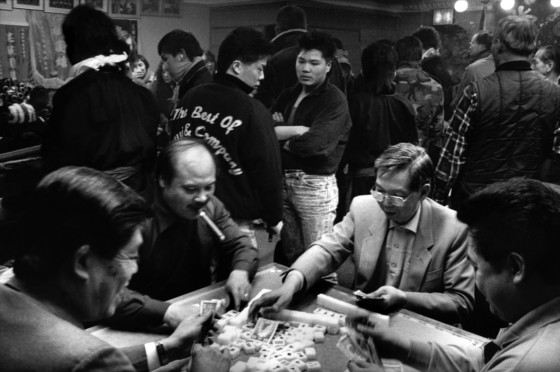

Speaking at the Magnum Photos Now Barbican event, filmmaker Sophie Bassaler recalled some of her conversations with other Magnum photographers about drawing inspiration from cinema: “Gueorgui Pinkhassov was hugely inspired by the vision of the great Russian filmmaker Andrei Tarkovsky. When he saw Solaris for the first time he told me he had a sort of epiphany and that would go on to hugely influence the spiritual nature of his work. And the case of Patrick Zachmann is just magnificent. His photographs of the Chinese mafia, the Triads, in Hong Kong and in New York are very much influenced by Chinese films made in Shanghai in the 1930s.”

"[Patrick Zachmann's] photographs of the Chinese mafia, the Triads, in Hong Kong and in New York are very much influenced by Chinese films made in Shanghai in the 1930s"

- Sophie Bassaler

Filmmakers inspired by photography

The relationship between cinema and photography “goes back and forth,” said Gruyaert. “I have talked quite a lot with directors of photography and directors of movies who tell me that they are influenced by some of my pictures.” One director Gruyaert worked with in Egypt explained that Gruyaert’s sense of composition helped the director to find order in the frenetic city of Cairo. Similarly, in an interview with LensCulture, the Polish cinematographer Ryszard Lenczewski, said that Magnum co-founder Henri Cartier-Bresson was his “master”. “He was able to catch ordinary moments while finding something metaphysical within them. In my house, I have a darkroom. Hanging in the darkroom is a poster of a guy jumping over a piece of wood,” he said.

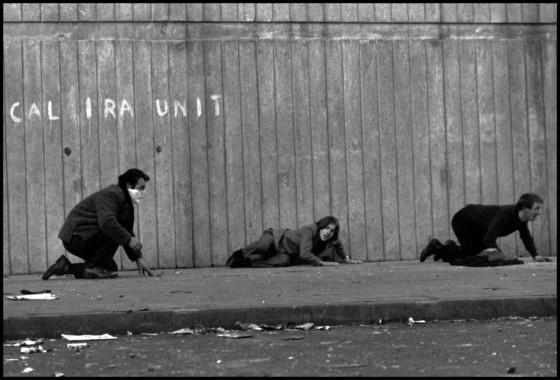

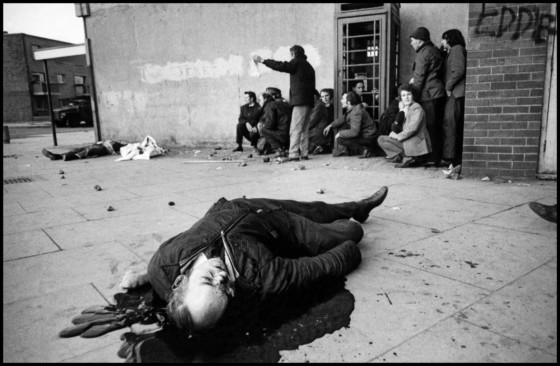

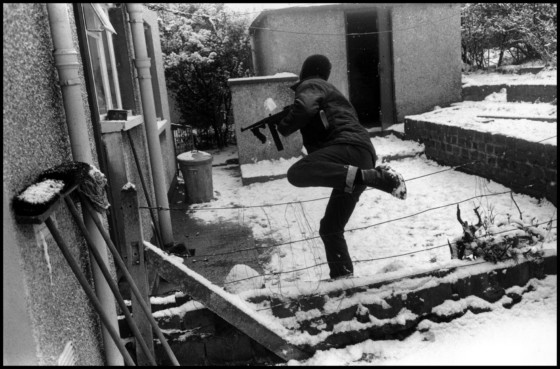

The inspiration filmmakers take from the work of Magnum photographers has, in some instances, been more literal, as filmmakers look to the documentation of major historical events, as captured by Magnum photojournalist, for reference. Some iconic Magnum photographs have been recreated almost exactly as frames in films. Robert Capa’s photographs of the D-Day landings were said to have served as Steven Spielberg’s reference point when making Saving Private Ryan (1998). While Gilles Peress’s harrowing photographs from Bloody Sunday, which took place in Derry, Northern Ireland in 1972, and included the iconic shot of victim Barney McGuigan that was splashed across newspapers the following day, played out as scenes in the 2002 film based on Don Mullan’s book. Also featured in the film was a photographer, seen ducking gunfire to capture his pictures: both a subtle acknowledgement of the key role played by a photographer that day in 1972, and an example of the filmmakers’ meticulous attention to detail.

Worlds Combine

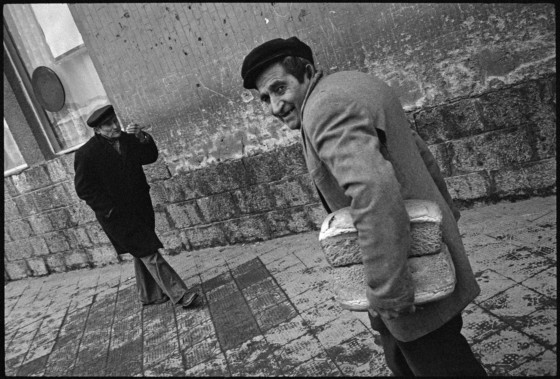

On occasions where both filmmaker and photographer worked side by side, focusing on their individual area of practice, the two can produce new perspectives on the same location. Josef Koudelka accompanied director Theo Angelopoulos during the making of his film Ulysses’ Gaze in 1994. Rather than aping the old ‘on set’ photography of times gone by, Koudelka, who travelled around with the film crew, used the opportunity to explore locations in Romania, Albania, Bosnia-Herzegovina and The Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. With no obligation to shoot what was being filmed for the movie, Koudelka shot towns, natural landscapes, market places and local people, creating his own authored view of the countries and offering an alternative perspective to the one depicted in Angelopoulos’s film. Czech photographer Koudelka has continued his relationship with Cinema, most recently becoming the subject of Israeli-born photographer Gilad Baram’s film Koudelka: Shooting Holy Land, which follows Koudelka during a four-year project photographing the harsh realities of conflict in Israel and Palestine.

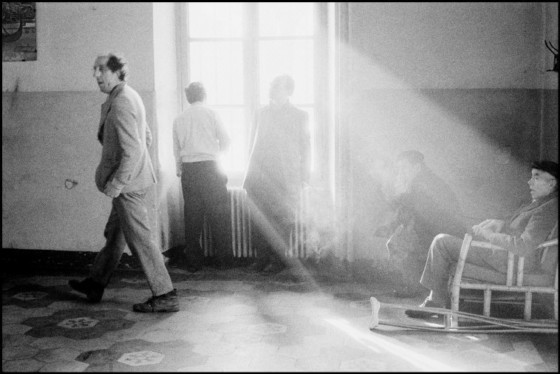

If a photographer is equally skilled in both film and photography, one photographer may even produce both of these perspectives. Raymond Depardon‘s study of the San Clemente mental asylum in Italy was a photographic study, but also the subject of Depardon’s 1982 film of the same name. He, according to Gruyaert is “maybe even a better movie maker than photographer. It’s extremely rare.” “The movie of it is fantastic and the photos of it are fantastic and it’s about the same place. It’s very interesting because you see a different approach to things.” Depardon continues to produce film work. His film Modern Life (2008) continues his exploration of the French countryside, as Depardon casts an affectionate and irreverent eye on a small community of farmers as they are confronted by the problems and challenges the contemporary world brings. “Poised and poignant…draws fascinating and subtle insight from individuals whose cherished way of life is slipping away,” states the Time Out New York review.

Read about more discussions from the Magnum Photos Now events here.