A Quiet Observation: Deconstructing Hannah Price’s Portraits of the Everyday

The Magnum nominee’s images capturing people at their most understated reveal the importance of listening in photography

As part of Magnum Photos’ recent Emerging Writers in Residence program, six early-career photography writers were invited to research and respond to a topic of their choosing in Magnum’s photographic archive. This text is one of the works that were produced on the residency — see all six at the link here.

Pelumi Odubanjo is a London-based multidisciplinary artist, writer, and curator whose work explores the intersectionality of women, migration and black identity as means to unravel our understanding of archival practice. In the following exploration, Odubanjo responds to the portraiture of Hannah Price. Unpacking the sensory qualities of Price’s photographs, she examines quietness as a phenomenon within the work which allows for a more holistic interaction with the images.

A photographic encounter enacts itself through a protocol that is often presumed to be universal. The photographer raises their camera which is thought to be the signal that an image is being captured; a flash, shutter, or a click signifies the end of the interaction. But what happens before and after this act is performed is unique to every photographer, subject and place.

In her 2017 book Listening to Images, Tina Campt refers to the quiet practice of photographing Black life as a ‘quotidian practice of refusal’. Campt highlights the possibility to create, within the constraints of the subjugation of Black life which diasporic peoples are often bound beneath. She relates the idea of quietness to those that are ‘assumed to go unspoken or unsaid, unremarked, unrecognized, or overlooked.’ A quotidian practice is one which goes far beyond a visual engagement that relies purely on what we see. The quiet here does not denote an absence, but instead, it is something that is registered as impactful as it ‘creates the possibility for it to register as meaningful’ in the everyday images of Black life.

Photographs cannot speak for themselves and one portrait alone cannot exemplify the fullness of the humanity pictured. In her work, Magnum nominee Hannah Price (the only Black, female photographer included in the membership as of 2021), depicts the masterful interaction that can occur amidst two strangers; the photographer and their subject, through the quiet methods of watching and listening.

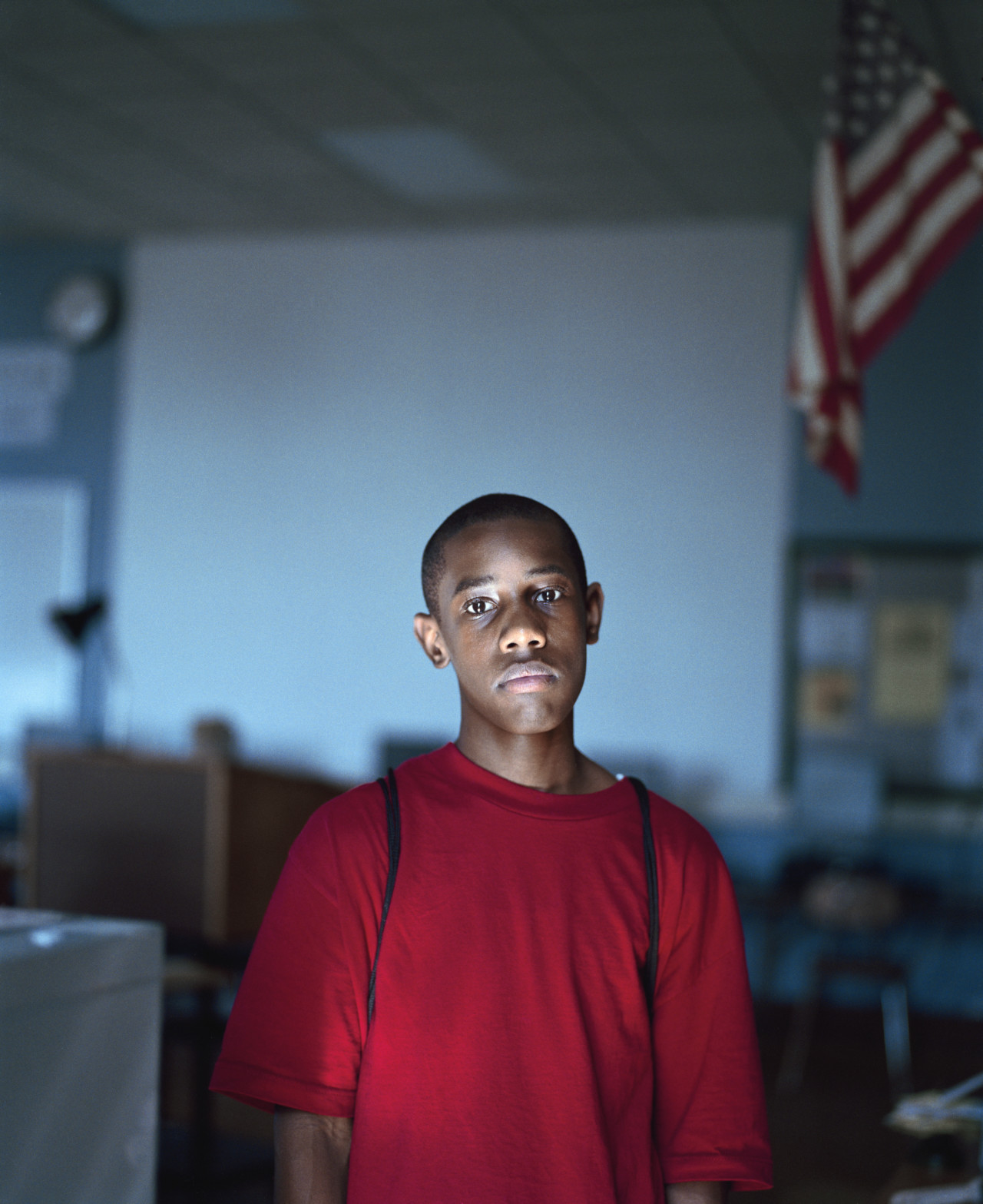

Price’s portraits depicting subjects of African-American heritage sit in a space of trust, community, and an intimacy that should be read beyond what we understand as the ‘gaze’— a dynamic that is inherently invasive by its nature and has previously been characterised via frameworks of feminist, race and postcolonial theory. One must consider how these images sit within a Western hegemonic culture that hinges on both racism and sexism, and how looking at and ‘gazing’ is formed within a microcosm of power relations that can repeat itself within photography. Price’s images should not be considered simply through the typical paradigm of someone invasively looking and someone else being unwillingly seen, thus signifying a loss of autonomy. Instead, Price’s photography is exemplary of the expansive potential for the individual experience in its depiction of the everyday and muted aspects of contemporary Black American life. Muted here should not be taken as an implied silence. It is within the smaller and overlooked crevices that Price finds a way to illustrate the happenings that play out from the streets of Philadelphia to schools in New York, each which suggest an abundance of life through the lens of her camera. Through her artworks, Price asks us to expand our visual cue of Blackness, and to instead listen to what is heard through the stillness of her subjects.

In her image of Aaliyah, the subject stands front and centre, her hands resting on her hips, angled away from the camera, with her eyes also averting the lens as they glance beyond the frame. The sun is setting, illuminating all that sits beneath it. The rose blush blossoms behind her merely complement the glow which radiates off her skin and face. It is hard to take your eyes off of Aaliyah. Here, Price uses colour to her advantage, making it difficult for the viewer to look away without first identifying each corner, each shadow, and each hue we see before us.

The colour blue from the view of the sky granted to us by Price draws the viewer into a state of wandering reflection which exists beyond this reproduced setting. Creating an elastic landscape which occupies the majority of the left side of the photograph, Price presents more than a simple backdrop. This blue acts as a frame without edges or corners, with no beginning, and no end. Her subject both inhabits and conducts herself though the colour of blue; free and uninhibited, without borders, horizons or restrictions, creating a space of internal contemplation and exterior projection. In its understated treatment of the Black, female subject from a Black and female perspective, the image is not only a rare addition to the Magnum archive, but also necessary intervention and declaration. This Black subject, this Black woman, is not here solely for my consumption and projections, nor yours.

"I’ve just always been interested in people. It's very odd because I am introverted. when photographing people, there's always something to learn about."

- Hannah Price

Aaliyah is not only avoiding the viewers’ stare, but she is also directly looking away from Price, and Price has allowed her to do so. Would this have been the case if Hannah were white? If she were male? Would perhaps a photographer who fits into either of these categories request that Aaliyah look directly at them? In her 1992 book Black Looks: Race and Representation, Gloria Jean Watkins — better known by her pen name bell hooks, puts forth her idea of the oppositional gaze where she states that “there is power in looking”. Speaking primarily in relation to Black, female spectatorship and representation in film, hooks defines the idea that Black people, namely women, have a right not only to observe, but also construct and direct their gaze, using our ability to look as agency. If repressed, this creates a “rebellious desire” to look. It is this rebellious act of looking that hooks defines as “the oppositional gaze”, one which cultivates a power to see, enabling Black female spectators to document and construct their own narrative with their own voice.

Aaliyah’s non-gaze here speaks volumes. Black women are so often forced to look, and simultaneously accept that they are to be looked at, thus becoming an object in countless interactions. Through her non-looking, Aaliyah communicates with the viewer what a direct stare back would not.

Speaking with Price after having studied this image of Aaliyah, Price shares details of the 2018 meeting – “I was hired to photograph Aaliyah. She was a part of this youth programme for students for this radio station in Philadelphia…I was hired to photograph Aliyah and her son, really because of their story…I think it was about an afternoon. I remember getting along really well.” Price later goes on to say, “I’ve just always been interested in people. It’s very odd because I am introverted. When photographing people, there’s always something to learn about. I just think people are interesting. I guess it’s my way of getting to know people: learning about them through imagery.”

In Price’s 2008 series Resemblance shot in Rochester, New York, after-hours near a local high school, a student is pictured leaning against the mustard wall of an unidentified building. This simple and hushed image showcases the young woman amongst a sea of yellow hues, accentuating her brown skin and disarming look as she stares into the lens held by Price. The face is soft and still. If it were to resemble a sound, it would resemble a soft blow in the wind. The prominence of yellow expands from the skin and clothing of our subject, all the way to the pastel halo which surrounds her as it glides from the foreground to background, with the brightest spot of the image appearing just behind her head and shoulders, through the hoop of her golden earring as if a doorway to a holy land. The longer one looks, the more it appears less yellow, and more golden. Indeed, she herself is golden.

Faces are arguably the most identifying physical feature, from which so many define themselves and others with. The face can demonstrate characteristics or the personality of a person: however, within portraiture, the face remains an incontestable feature of the work. In portraiture, you are not simply viewing a captured image, but rather the reproduction of a face. Although the viewer can interpret some expressions on the reproduced face, they will not decode the mind in its entirety. Often it will elude one’s full understanding. Only Price knows what in, or about, their meeting influenced her subjects’ facial contortions. Surely if we, the viewers, were to know this answer, then how we read the image would be altered.

What was the allure of these individuals, for Price? “What got me into photography was family photos,” she says. “And even without photos, I just loved seeing similarities within families, you know like features, even mannerisms and just a way of being. I think that’s just really interesting. So when I photograph people, I’m looking at them and getting to know them. It’s about their beauty, and learning about them in that moment, more than making a typical portrait.”

Price’s 2009 photo series City Of Brotherly Love catalogues portraits of various men across the streets of Philadelphia who had catcalled her on her daily travels. Speaking about her approach to this series, Price says “I made this series just based on experience. Growing up in white suburbia, and suburbia in general, no one catcalled. This is just me being unfamiliar with such a manner. The whole project is like a diary for me, and like a transition in my life, taking power from a man into my own hands. It’s especially [a diary] of a sexual gaze that I don’t like. I took it, and made it what I wanted out of it.” The camera in this scenario is a tool which allows Price to subvert the situation, and ultimately reflect the dynamics which underlie catcalling. Reconfiguring the act, and turning eyes on these men, Price creates a work specific to her everyday encounters as a woman in regards to her sexuality, body and control.

In Price’s portraits; the lighting, composition, and even positioning of the subjects themselves vary so much that viewers have plenty of freedom to fictionalise these encounters, albeit within the framework that Price has provided. Take this image, ‘Walking from CVS. West Philadelphia’ from the series. As the viewers’ eyes traverse the landscape of this photograph, they land in varying places: the glistening sweat reflecting off his tattooed upper body as he straddles his bicycle, with his hands on the clutch, as if, immediately after Price has taken the image, he will be on his way.

The backdrop here is not used to accentuate nor beautify the subject, nor is it banal. This backdrop is completely reflexive, with the window making visible the building and vehicles on the opposing streetside. How many people on the street saw this encounter, be it through their window or in person? If Price were to have moved even an inch towards the right for taking this image, we might have seen her in this window. What would this change? Would this photograph have taken the form of a self-portrait? Would we then feel differently about the presence of Price within this encounter? Even without Price’s reflection, what is implied through the presence and simultaneous non-presence of Price and her camera?

How can photography be used to highlight subjects often overlooked in our visual culture? Is it possible for photographs to reconstruct a subjectivity out of figures who we often deem essentially mute? How do we engage with these photographs? And what does that say about us?

The photographic encounter is complicated. It involves asking for and being granted permission. When done ethically, the process is collaborative, creating an open and dynamic framework which exists not only between photographer and subject, but audience and image. Price’s work allows viewers to participate in the moment of photography, pushing them to look and listen beyond their peripheries, and expand our notions of how, and why we observe.

“I always try to relate to my subjects,” Price says. “I always think that every human being has something to relate to in each other, just by the fact that we’re human. That’s how I approach people in general, but in image-making, and when I’m making a portrait, I relate to the person. I want emotion, and genuineness in the portrait. With Resemblance and City of Brotherly Love, I wanted to make the most beautiful portrait that I could possibly make. It was for our time together in that moment and the connection between us.”

When engaging with black subjects within portraiture, the social uses of photography must go beyond the stylistic and aesthetic interpretations that have been inherited from art history. Historically, black people have been the preoccupation, subject and object of many photographic discourses, which have frequently been misrepresentative. It is beyond the frame and beyond the photographer’s boundaries that we need to extend our line of questioning, to enable us to participate critically.

For some, the gesture of lifting a camera and pointing the lens towards someone symbolises the beginning of the act, and the penultimate print or digitalisation of an image symbolises the completion of the process. Price’s practice stands as counter to this. Through subject, composition and its expression of intimacy, Price frees photographic portraiture from its history and its traditions, creating a place where new meanings arise, and where we can encounter ourselves through our interaction with the other. Price neither interrupts her environment or restages her subject to the extent that the dynamic in which they met becomes lost. Instead, she sets the stage for another dialogue; one which requires mutual attention and looking, creating a series of gentle interactions where we are ushered to be still and listen to those that are quiet.

Pelumi Odubanjo (she/her) is a London-based multidisciplinary artist, curator, researcher, and writer. Her work revolves around archival imagery and contemporary vernaculars around image-making informed by a black feminist epistemology. Pelumi works with artists, archives and cultural artefacts to create and explore dialogues across a global African diaspora, and unravel historical and contemporary links between the intersectionality of women, migration and identity as means to unravel our understandings of archival practice.

Her recent work includes curating for the Tate Exchange and Brighton Photo Fringe, co-founding the art research collective Contakt Collective, and working as curator-in-residence at the Black Cultural Archives (2020).

This project was made possible thanks to support from The National Lottery Heritage Fund.