Rafal Milach on the Use of Visual Metaphors to Deconstruct the System

The 2018 Magnum nominee's approach uses a variety of mediums to unpick the transitionary state of the former Eastern Bloc

Photographer and visual artist Rafal Milach studied graphic design at the Academy of Fine Arts in Katowice, Poland, before ‘falling in love’ with photography the first time he picked up a camera. He grew up in Poland during the collapse of the Soviet Union and as a result his work often uses the transformation of the former Eastern Bloc as a lens through which to address wider issues. Though he initially tackled subjects through a traditional documentary perspective, his later projects draw on a more abstract approach, as he attempts to deconstruct global systematic structures. Whether taking photographs, making award-winning photobooks or repurposing historical ephemera, the various mediums Milach engages with aim to give the viewer the tools to question the world around them. Here, the 2018 Magnum nominee discusses the cyclical nature of history and humanity and why he is fearful for the future.

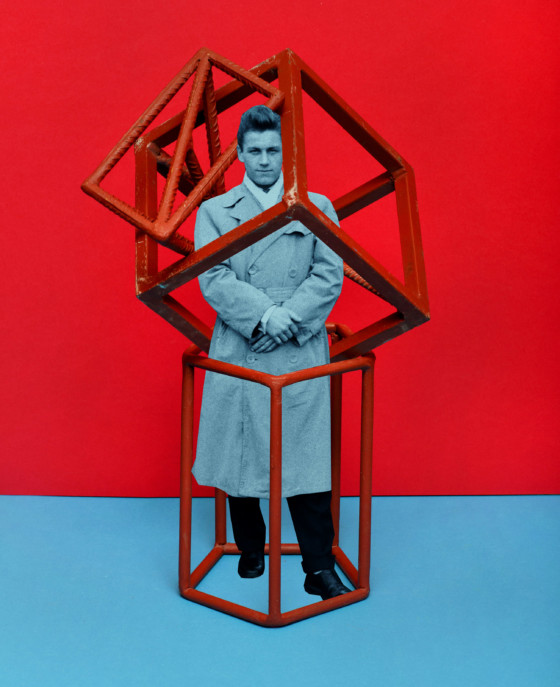

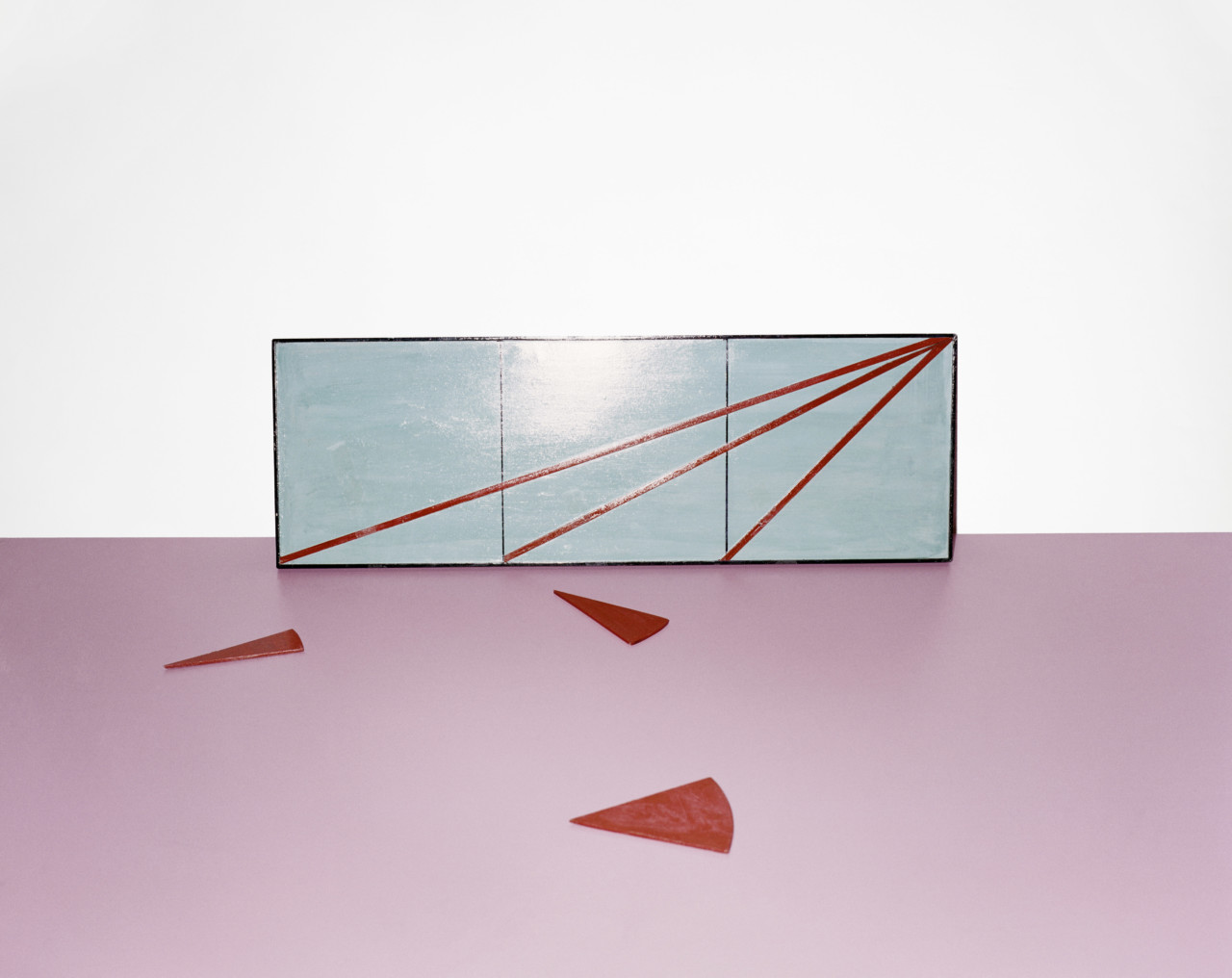

The above image is included in the new Magnum Editions Posters collection, featuring contemporary works from 23 Magnum photographers. These posters are now available, in limited editions of 100 unsigned, and 50 signed priced at $100 and $150 respectively. Each poster is individually numbered with a unique Magnum Editions label that is supplied separately. You can explore the whole collection here, and see Milach’s here.

You were a student of graphic design before you came to photography, are you glad you took this roundabout path?

Yes, I’m glad I have this experience of being a graphic designer before coming to photography. All kinds of experiences build up our perception – having experience of a variety of mediums gives you distinctly more possibilities when choosing whatever visual language is necessary to communicate the story.

At what point did you decide that photography was what you wanted to focus on?

That was quite accidental and not romantic at all. I was studying at the Academy of Fine Arts in Katowice at the time and I just had to pass the photography course – that’s how it started. Surprisingly, I fell in love with a medium that I’d never used before.

What was it about photography that made you feel it would appropriately express what you wanted to convey?

With photography, I found myself in a totally different field. Observing and being open to what’s around me in the so-called ‘real’ world was interesting to me. Today, I question that ‘realness’ more and more often. But I shifted from the ‘imaginary space’ to photography, which offered some sort of realism. I got the opportunity to go to places and meet with people. It was exciting but also challenging for the introverted person I was back then.

And do you think your work has more recently taken another shift again away from this close relationship with your subjects?

Yes, I would agree with that. It’s because I have become more interested in larger structures with socio-political contexts in the foreground. I found it relevant to step back from the personal feel that I was first attracted by when I was starting out with photography. People’s stories are still part of this puzzle, but my main interest at this point is focused on the larger constellations that I try to deconstruct in different ways.

"Power structures are either invisible to us or we choose not to see them. I try to find different ways of deconstructing these ideas"

- Rafal Milach

Your work often grapples with themes of political manipulation and control, which are big topics and difficult to approach from a traditional documentary photography perspective. Is that why you felt you needed to move into a more abstract approach? As a way to tackle these larger themes?

Yes, I feel this is more relevant to telling the stories that I want to tell. I don’t claim it is the only solution, but the ideas I comment on are very abstract. They are relatively simple to describe with words but more difficult to visualize, power structures are either invisible to us or we choose not to see them. I try to find different ways of deconstructing these ideas, each time trying to find a proper visual language – I believe a multitude of approaches can help the viewer understand the complexity of the problem.

It sounds like you’re almost seeking a collaboration with the viewer… that the piece of work is not the final end-point and you then ask the viewer to be drawn into your questioning?

I don’t offer solutions. This abstract aspect of the work is very much linked to the context of things; some elements of the work require some sort of guidance – a backdrop, rather than an explanatory text. So I give the viewer the tools to deconstruct these mechanisms themselves.

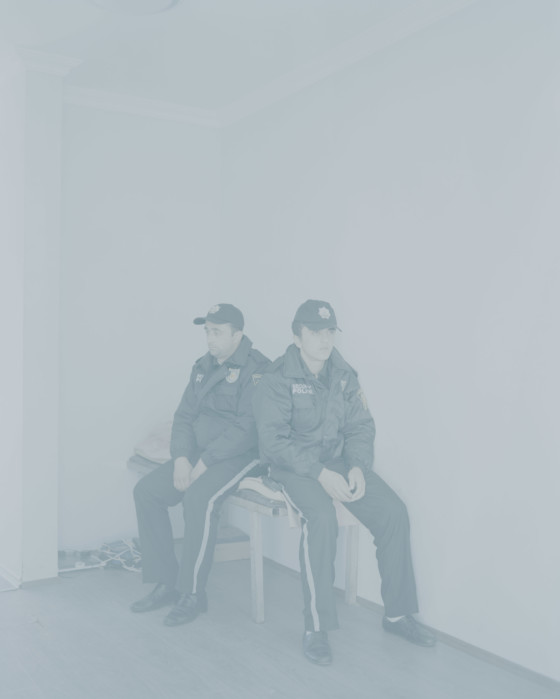

To give you an example; with the Winners project, which documents the winners of various contests organised by the Belarusian authorities, I tried to withdraw myself as the author of these pictures, in order to create a potentially neutral image. So the pictures could be viewed as critical if we come to them from outside the country, let’s say from the Western culture or from a ‘democratic’ culture (although this term is a stretch given the current climate of corruption). But the pictures could also somehow be confirming material for Belarusian authorities. They could work both ways depending on who might potentially use the material.

This leads me on to a subject which seems to preoccupy a lot of your work; the concept of propaganda. Why is this an ongoing interest for you?

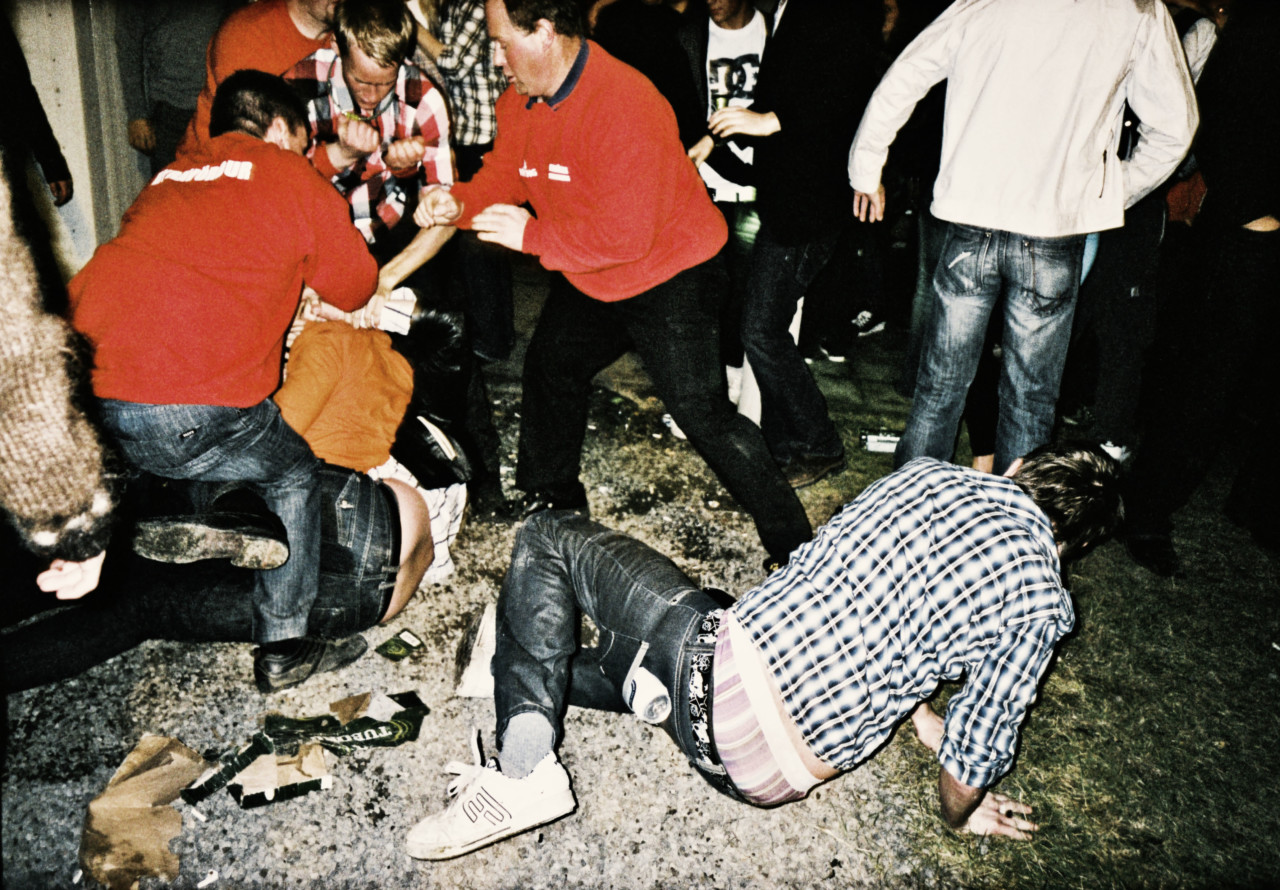

It all started seven years ago, with the Winners work. That was the first project where I stepped back from that personal feel – which I mentioned before – to focus on bigger patterns. I kept going with the other chapters which I finally shaped into a structure: a project called Refusal. It’s a growing collection of various models and situations that deal with propaganda, manipulation, control and so on.

The environment has changed since I started work on Refusal, back in 2010. Everything seems to be political today. Neutral fields no longer exist in my opinion, it’s a global trend, one that has intensified. Unexpectedly this project has become much more relevant than it was a decade ago. For example I would never have thought to include Poland so smoothly in Refusal’s structure, but when I look at it from a contemporary perspective given the disturbing political turn that my country took few years ago, I have to refer to it somehow. I wish this field wasn’t such an abundant resource for my work!

"Democracy is not something given to us for good, we have to take care of it and fight for it constantly otherwise it disappears and goes away"

- Rafal Milach

On that note, a lot of your work is concerned with the transformation of the former Eastern Bloc. You experienced Communism first hand growing up in Poland, how has that informed what you do?

All of my work on propaganda and manipulation is definitely linked to the transformation of former Eastern Bloc countries. My own personal experience is one of transition, I was a teenager when Communism in Poland collapsed and that somehow marked my perception of what’s around me. Since I have had this experience I feel somehow authorised to tell stories of this post-transition period, which is not yet a complete process. It is probably going to take decades at least.

There are of course the questions about our relationship to democracy and our civic responsibility. Democracy is not something given to us for good, we have to take care of it and fight for it constantly, otherwise it disappears and goes away. We are experiencing this in Poland at the moment.

You’ve made a number of photobooks—some of which are award-winning—what do you enjoy about the process? What do you see as being their value?

I like to present a book not only as a way to display images, but as a complete gesture which is linked to the wider work and should strengthen the idea of the project.

The construction of the book is important; the small gestures that we make with the size, the materials, of course the sequencing and editing of images. These are all elements that are crucial to me. And of course books offer a space for photography; it is a slow medium and books offer an intimate, one-to-one relationship between the viewer and the work.

"I don't want my work to be perceived only within the post-Soviet bloc, like some strange exotic sphere that doesn't refer to other places in the world"

- Rafal Milach

I’m interested in what your creative process is like with a project such as First March of the Gentleman, which relies heavily on archive material. Do you have a clear idea about approach before you arrive at a subject or is it the other way around?

Each project has its own dynamic, so there is no one rule that I could apply to all of them. With First March of the Gentleman, while I knew that I wanted to use archive, I didn’t know how it would actually work.

Initially it was supposed to be quite a surreal, escapist story about shifting the meanings of the archives I found in this small town. But following the political shift in Poland and the intense period of protests, I decided to respond to that in the project too.

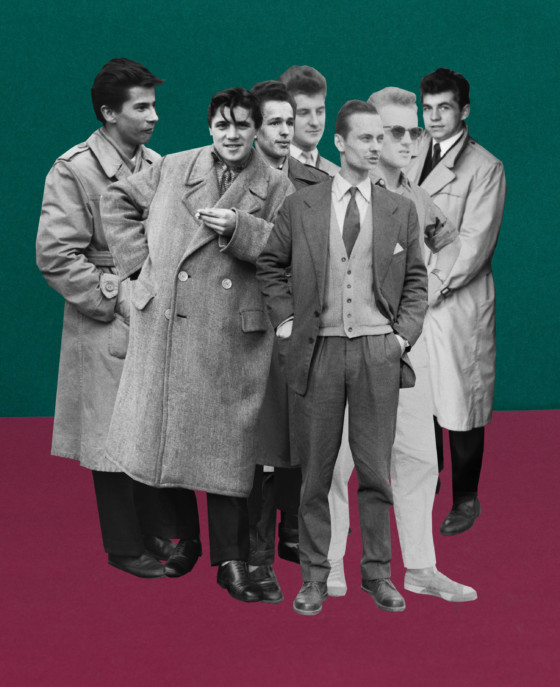

I found an amazing archive from a local photographer [Ryszard Szczepaniak] mostly operating in the 50s when the Communist regime was transforming from the Stalinist era. Somehow he found a space for himself to ignore the system and preserve his freedom of expression by toying around with his soldier friends doing crazy photoshoots: using their army uniforms and guns, which of course were illegal to bring to public spaces. The added layer of my project, which uses school apparatus that I have repurposed as ‘cages’, refers to the [Wrzesnia] children’s strikes from the beginning of the 20th Century, which were eventually pacified by German occupants.

It’s a clash of two spaces of freedom and pacification. With these parallels I could somehow build the contemporary metaphor, which is a comment on the historical loop that we are in.

It reveals the cynical side of human nature?

Oh yes, that doesn’t change. And apparently we don’t learn, it’s incredible. It’s so frustrating. When you see the Neo-Nazis marching through Warsaw…the presence of that ideology should be completely banned from the public space, especially when there is such a clear historical trauma that Poland has experienced.

Does your need to create work come from a place of frustration, anger, or both? Is that what drives you?

Usually not, actually. Usually I try to digest things slowly and to build constructs. But in this particular body of work [First March of the Gentleman] and my upcoming book [Nearly Every Rose on the Barriers in Front of the Parliament], it does come from anger and frustration, but also from fear. I think about what might come next? It’s something I’m afraid of and I have to work on it. It’s a warning that I’m creating for myself and for the viewers.

Which country have you found most challenging to work in?

Actually Poland, because it’s my own back yard. I have access, I understand the language and the context and of the place, but at the same time that is paralyzing because it gets very emotional. I function here on a daily basis so sometimes it’s hard to step back from the things that are surrounding me everyday. You are an insider and so it’s easy to fall into clichés and you don’t notice processes that are so close to you.

You’re part of the system in a way that you’re not when you’re a foreigner?

Exactly. And everything seems so uninteresting. You think you know it all. It still disturbs you, but in a different way. You can digest it on daily basis and this is often the problem, because in such a manner you ignore a lot of things.

Is that exactly why you think it is important for you to make work about where you’re from? So you challenge yourself and don’t internalise things, instead confronting them head on?

Yes, absolutely. But even though I mostly work in this region and in the post-Soviet territory, I really try to refer to bigger patterns. I don’t want my work to be perceived only within the post-Soviet bloc, like some strange exotic sphere that doesn’t refer to other places in the world. It’s important to communicate the problems I touch upon in my projects beyond the geographical context.

Milach’s new book, Nearly Every Rose on the Barriers in Front of the Parliament, is published by JEDNOSTKA Gallery and is available for pre-order here.