Robert Capa: Death in the Making

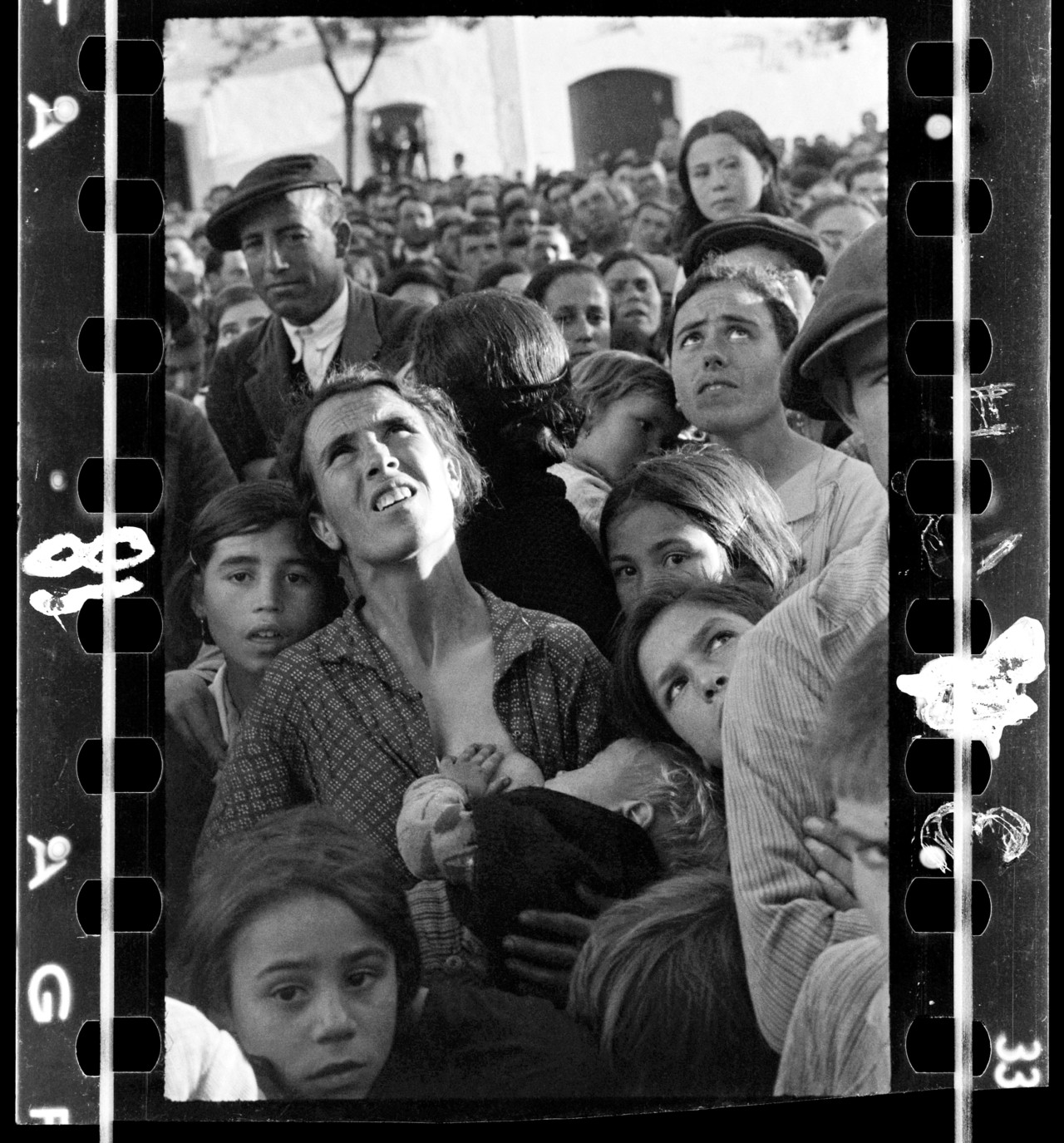

As Robert Capa’s famed monograph on the Spanish Civil War is republished, its editor Cynthia Young discusses the work and its impact on the Magnum Photos co-founder

Cynthia Young, former head of the Robert Capa Archive at the International Center of Photography and curator of numerous exhibitions on photojournalism in the 1930-50s (including Capa in Color; We Went Back: Photographs from Europe 1933-1956 by Chim, and The Mexican Suitcase: The Rediscovered Negatives of Robert Capa, Chim and Gerda Taro) is the editor and author of the new edition of Capa’s Death in the Making.

Here, Young and Magnum’s Cultural Director, Pauline Vermare, discuss this new edition of Capa’s classic photobook on the Spanish Civil War, which features an introductory essay by Young, as well as a new and fulsome inventory of the images, the researching of which has shed light on both Gerda Taro and David ‘Chim’ Seymour’s contributions to the volume.

The following article contains images that some readers may find distressing.

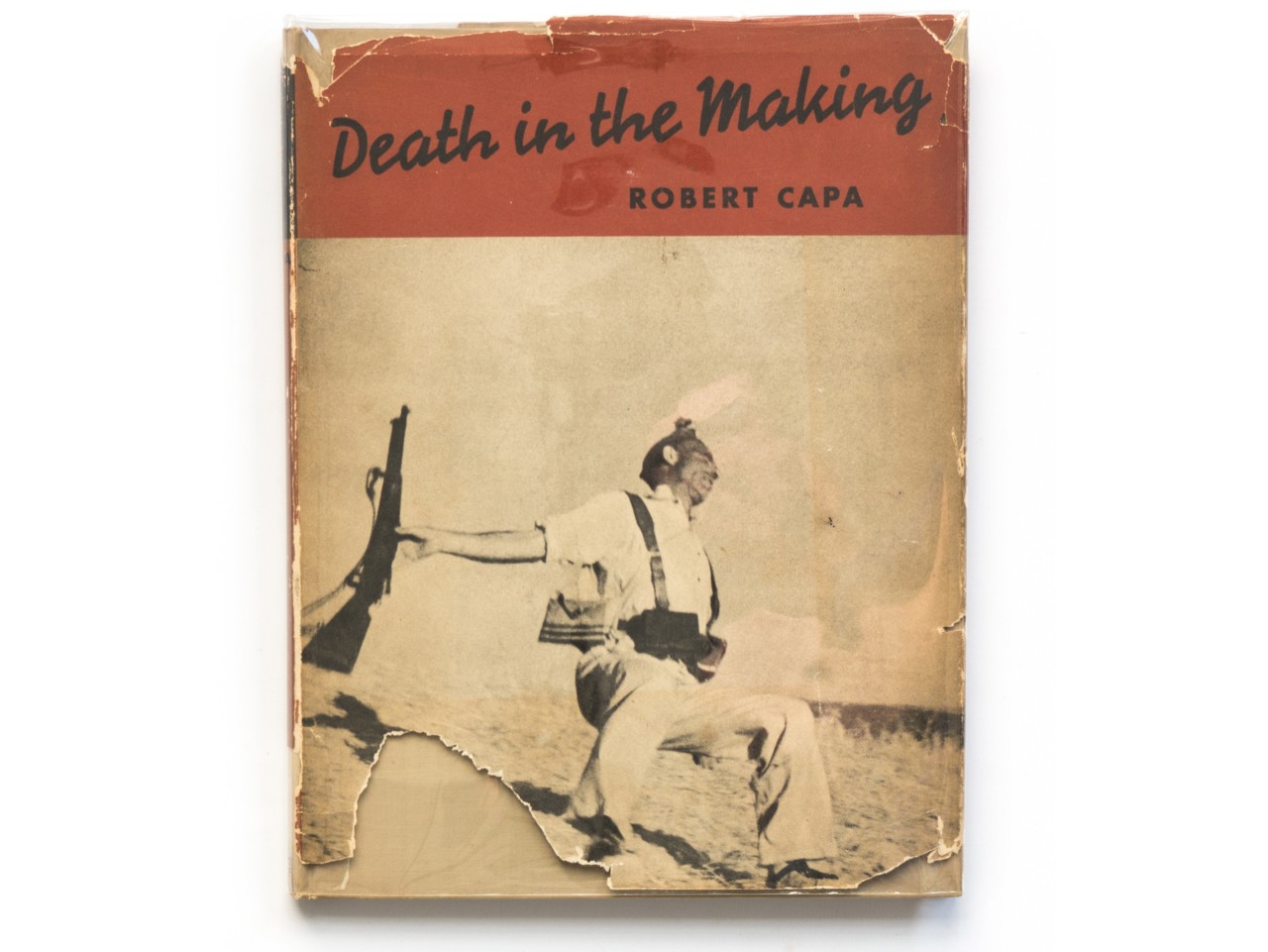

Pauline Vermare: Death in the Making was originally published by Robert Capa, in1938. This new edition is a long time coming, and an exciting moment for photo-historians, photobook aficionados, and fans of Capa’s work alike. Can you first tell us about the original book?

Cynthia Young: The original book came together during Capa’s first trip to New York, in the fall of 1938. This was just two months after his professional colleague and romantic partner, the German photojournalist Gerda Taro, had died working in Spain. He came to New York to see his brother and mother, but also to renegotiate his relationship with New York photo agencies. In the midst of this, Capa reconnected with his Hungarian friend, André Kertész and American journalist Jay Allen and a book project got off the ground. It was published to modest success, and probably in limited supply, but over the years has become a sort-of underground, cult book.

What triggered the desire to reprint it?

Copies of the original book have become increasingly rare. Ten years ago, you could easily find a copy for less than $50, but now copies go for several hundred dollars, if you can find one at all. And those you could find are often without the dust jacket. Even rarer and even more expensive are original and intact copies. So, there seemed to be a growing interest in a new edition.

Can you tell us about the thought-process behind the new edition and changes to the original? What you were trying to do, and perhaps trying not to do?

The goal was always to create a facsimile edition, to make this book available for a new, current generation. Other photographers have gone back to their early publications and re-edited their work for a new publication, but as none of the original contributors to Death in the Making are alive today, a new edit would be a new book. I wanted to publish a complete checklist to the images because while the original book credits Capa and Taro as the photographers, there is no indication of who took what, and Chim was not mentioned as contributor at all. It was also important to print the images in higher quality than the first edition, in which they looked muddy and flat. Unfortunately, we did not have negatives for all the images in the book, some only existed as vintage prints, and a few appeared only in the book, so getting consistent quality for all the images was always going to be the challenge. Damiani, the Italian publishers, understood that the source material for all the images was mixed, but immediately embraced the project and the subtle balance between respect for – and improvement on – the original.

You decided to keep the striking original cover, featuring the famed Falling Soldier image. Can you tell us about this choice of cover, and about the power and mythology surrounding this iconic image?

Unfortunately, I have not seen a book dummy or original notes on the project, so I can only speculate on the selection of the book cover in 1938. It is interesting that the image was not originally reproduced in the interior of the book. I suspect that was an omission indicative of the speed with which the book came together.

"In general, there is a dearth of knowledge about the Spanish Civil War in the United States, and the book was a casualty of that, despite the fact that over 2000 Americans volunteered to fight with Republican Spain"

-

Capa’s autobiography Slightly Out of Focus (1947) has become a cult classic – one can hear him talking about it here in this radio interview you released a few years ago. Death in the Making, on the other hand, his very first book, one of the first war photography books in history, designed by another legendary Hungarian photographer, André Kertesz – is surprisingly little known in comparison. Why do you think that is?

Slightly Out of Focus has been translated into many languages. A new edition in 2001 included an introduction by biographer Richard Whelan and a text by Robert’s brother, Cornell Capa, and more recently an audio book of it was released. It’s a fast-paced, at times silly, account of his World War II escapades and it was intended as inspiration for a Hollywood film script, which never materialized.

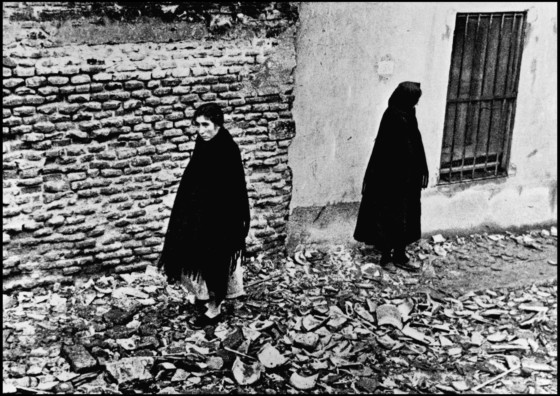

Death in the Making is an infinitely more serious book about the sacrifices of Republican Spain. In general, there is a dearth of knowledge about the Spanish Civil War in the United States, and the book was a casualty of that, despite the fact that over 2000 Americans volunteered to fight with Republican Spain.Within a decade of its publication, association with Republican Spain became a liability because of the association with communism. As a result, there was little continued interest in the book, except in certain circles.

"While Death in the Making does not include all of his best stories from Spain, and only those from the first year of the conflict, it did come at a time when Capa was trying to professionalize his career and solidify his reputation with American editors and readers"

-

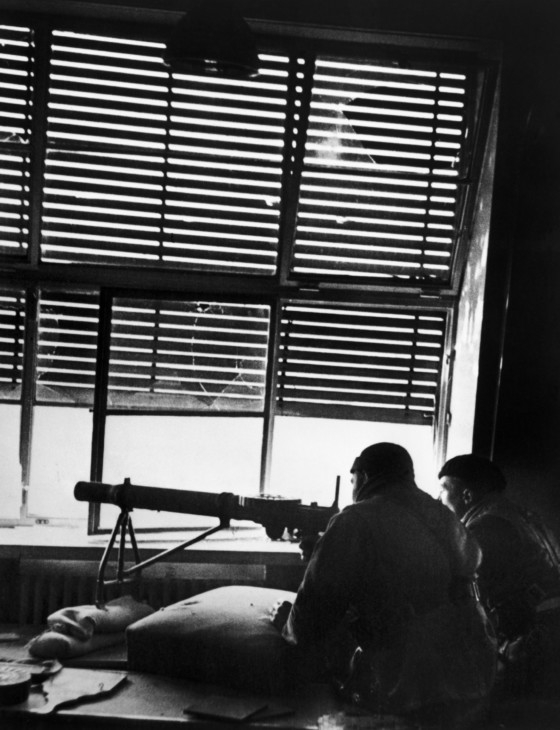

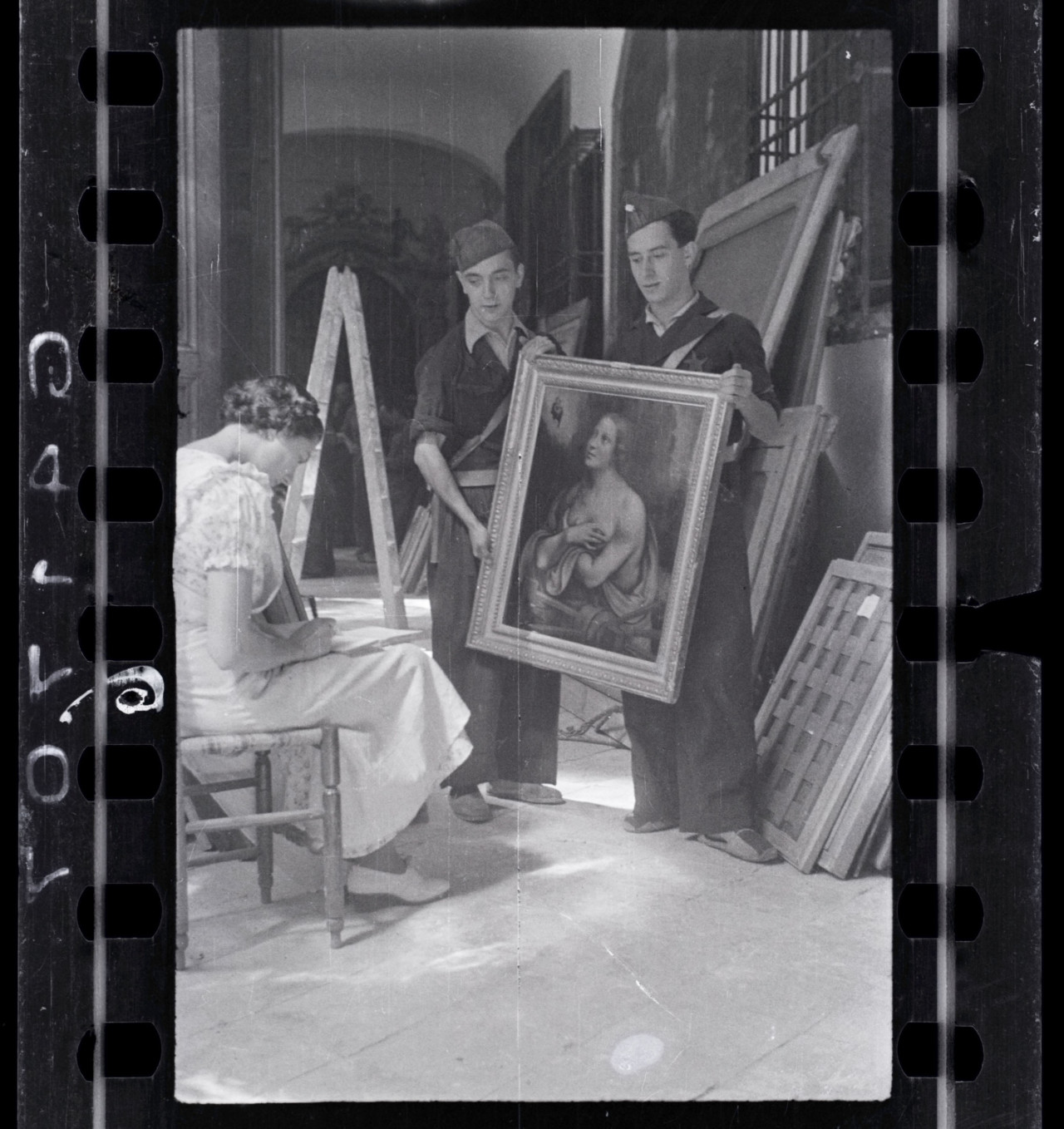

One of the revelations of this publication – triggered in no small part by the colossal research you led around the Mexican Suitcase over ten years ago – is the re-establishment of Gerda Taro and Chim’s authorship of some of the photographs in the book, all of which were credited to Capa in the original version. Can you tell us more about this in-depth identification process, and the discoveries you made along the way?

I know Richard Whelan recognized that Chim’s images were used in Death in the Making, because of his notes under some of the Chim images in his personal copy, however, he did not write about this. Once I started the process of creating the checklist of all the images, most were easily identifiable. The author, date and location can be verified through several sources. There are a few images in the book that I have not seen anywhere else, other than in the book. For those I could only make informed guesses, and they are accordingly listed with a question mark.

What was Capa’s relationship to this book?

The one thing we know about Capa’s reaction to the original book is that he was appalled by the print quality, as referenced in a letter to a friend. He was in China when the book was published, and did not return to New York until late 1939, after the Spanish Civil War was over, so he was not involved with a publicity tour or marketing campaign.

The book was certainly a reference point in his career, and over the next ten years he published three more books: The Battle of Waterloo Road (1941), Slightly Out of Focus (1947) and A Russian Journal (1948). While Death in the Making does not include all of his best stories from Spain, and only those from the first year of the conflict, it did come at a time when Capa was trying to professionalize his career and solidify his reputation with American editors and readers. It is interesting to remember he did not even speak English at the time. His mother, who was living in New York, was extremely proud of the book.

The Spanish Civil War was a turning point in history, as well as a turning point in Capa’s life and career. Can you tell us about these years, how they “made” Capa?

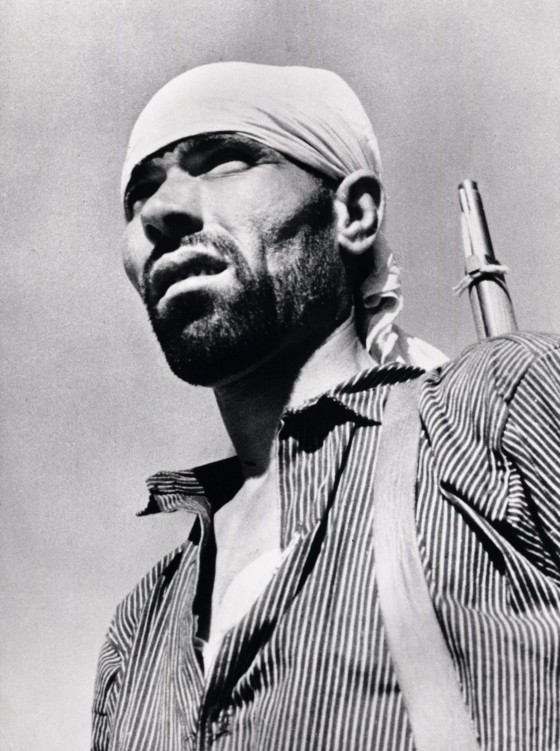

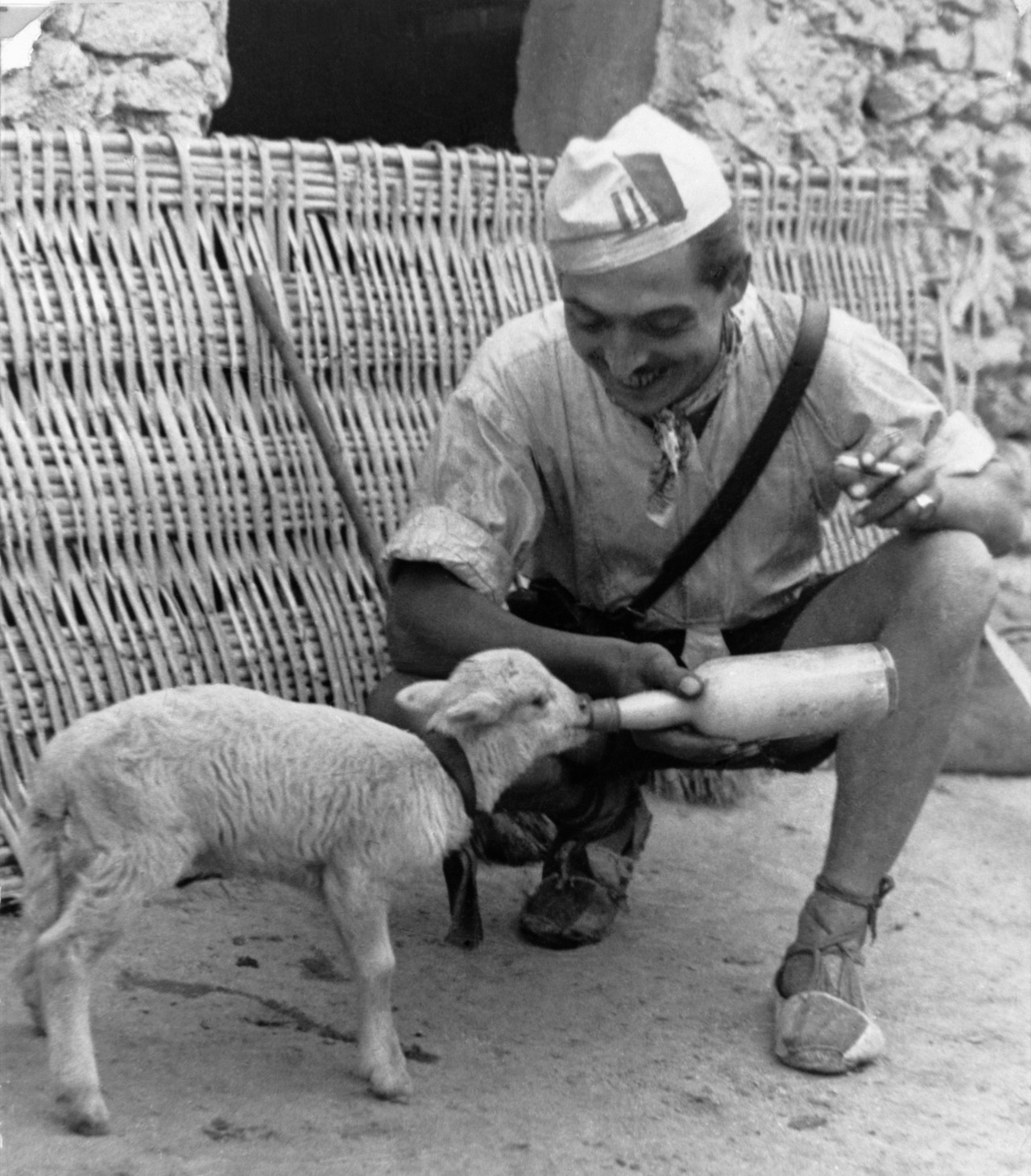

In the summer of 1936, Capa was just getting his career going. He photographed the parades and street demonstrations of the Popular Front in Paris before the Spanish Civil War began, but his images, when published, were usually without a byline. It was his striking images from the first five months of his time in Spain, in 1936, that catapulted his reputation onto an international platform. No longer was he an aspiring photographer, scraping by to get an occasional image in the papers. Now he was confident in his ability to pursue stories that the editors would publish.

"Today, the book once again puts faces to the fight to defend Republican Spain against Franco's fascist forces. It recalls the clarion call heard by so many international writers, artists, laborers, medical workers, and students to come to the aid of democracy"

-

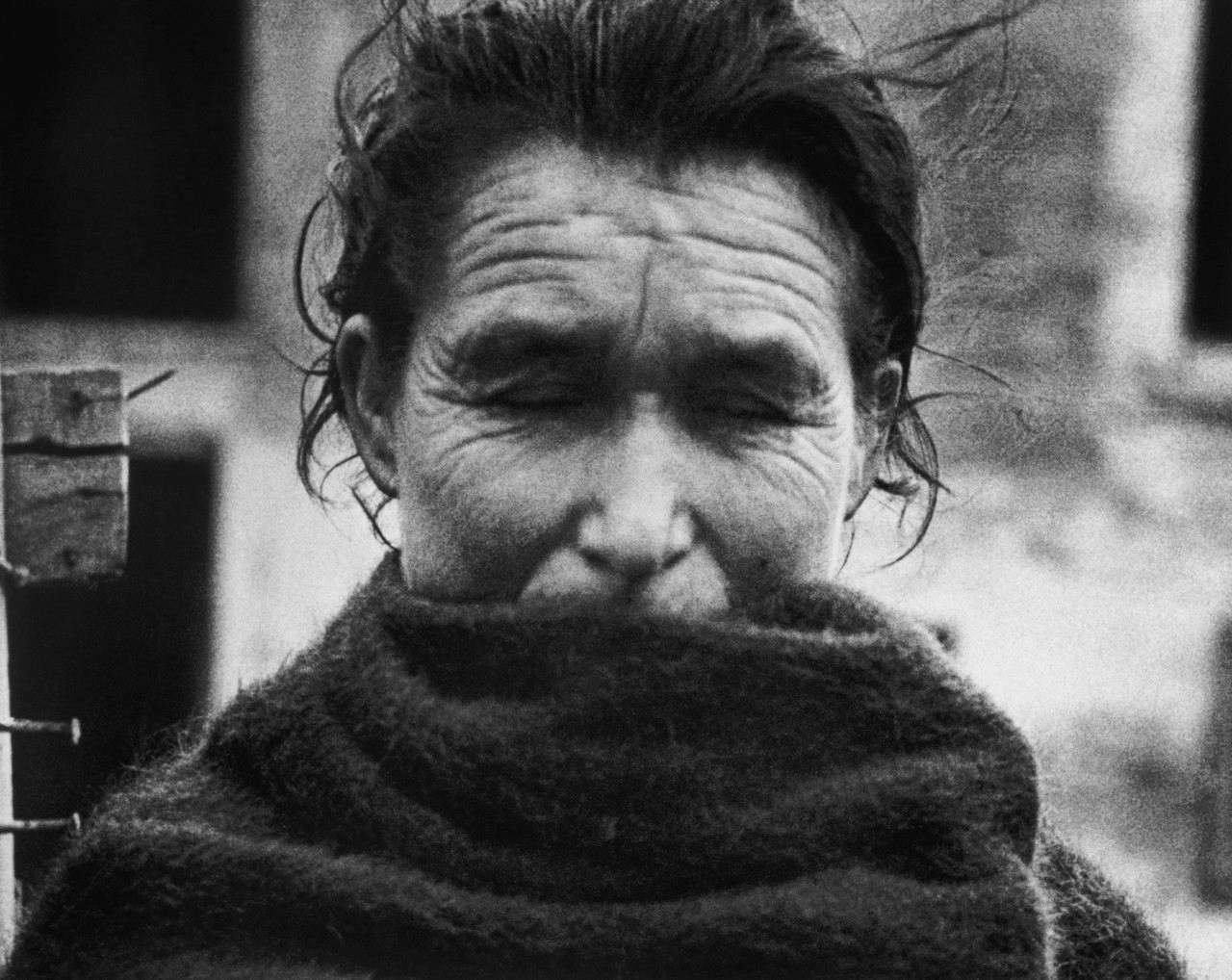

The book is, very movingly, dedicated to: “Gerda Taro, who spent one year at the Spanish front. And who stayed on.” In your essay, you write about the tragedy that her brutal death was to Capa. Can you tell us about their relationship, both human and creative?

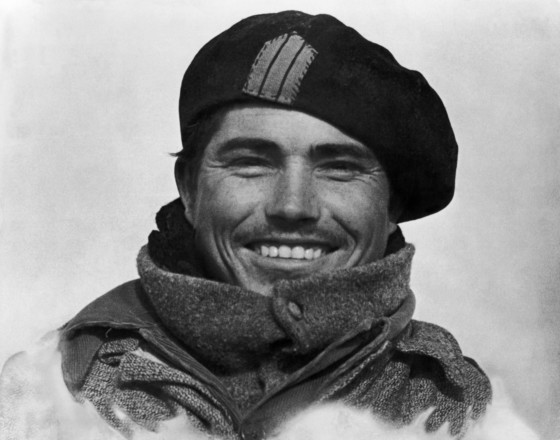

Capa and Taro met in Paris in 1933, where they resettled after experiencing antisemitism in Germany and Hungary. They soon became friends and lovers, and together changed their names. Andre Friedmann became Robert Capa and Gerta Pohorylle became Gerda Taro, short, snappy, and international sounding names that reflected their ambitions. Taro encouraged Capa to behave more professionally, and Capa taught Taro basic camera techniques. They were contemporary partners in the sense they both learned from and supported each other. He was, by all accounts, emotionally and physically devastated by her death.

Just as Capa, Taro, and Chim’s work in Spain was never just about making beautiful photographs, this book was never really meant to be just a photobook: it was a political act, using photography to alert democracies – the British and French governments – of the dangers of fascism and the need for intervention. The last paragraph of your essay in the book resonates profoundly:

Today, the book once again puts faces to the fight to defend Republican Spain against Franco’s fascist forces. It recalls the clarion call heard by so many international writers, artists, laborers, medical workers, and students to come to the aid of democracy. In the book, the complicated internal politics of the Spanish government are absent, images of the most gruesome deaths are not included. The cause is pure. It also reminds us not to remain idle in our own times; the threat to democratic norms from authoritarian leaders has not passed.