The Slow Cancellation of Eskîfê (Hasankeyf)

Images of a town which held a significant role in Kurdish history depict traces of its “failed future” and foreshadowed its impending destruction

As part of Magnum Photos’ recent Emerging Writers in Residence program, six early-career photography writers were invited to research and respond to a topic of their choosing in Magnum’s photographic archive. This text is one of six works that were produced on the residency — see them all at the link here.

Rojda Yavuz is a visual researcher and writer. In this essay, they discuss the destruction of the town of Eskîfê in Turkey, also known as Hasankeyf, touching upon its role in the Kurdish imaginary. Analysing images made by Carolyn Drake and Emin Ôzmen prior to the city’s flooding, which was planned by the government since 1975, Yavuz examines the psychological effect on a community which anticipates its own ruin by the state.

Note: information in image captions, written by photographers, were correct at the time that photographs were made.

The ancient town of Eskîfê —Hasankeyf, in Turkish— was located in Southeastern Anatolia along the Tigris river. Home to predominantly Kurds and Mhallami Arabs, the settlement dated back 12,000 years and was known for its beauty and many archeological sites. Assyrian, Roman and Ottoman monuments, thousand-year-old troglodyte architecture—cave houses, carved out of rock, as well as medieval remnants of the Artuqid dynasty: a stone bridge and mosque from the 12th century all rendered it a popular tourist attraction.

Kurdish lands and communities colonised by Turkey have been fighting for self-determination since the last century. Eskîfê played a particular role in the Kurdish imagination: many meanings of Kurdish identity and existence were derived from, and cast through there. The ancient site functioned as an archive that stored the lived history and the imagined history of Kurdish people. These encompassed the experiences and memories of the local population who lived on that land for centuries, as well as the ancient existence of Kurdish communities anchored in Eskîfê, the latter ultimately justifying the claim to the land.

In May 2020, the town and the 85 villages surrounding it were completely submerged as a result of the Ilısu Dam that was built on the Tigris river. This led to the eradication of one of the oldest continuously inhabited settlements on earth, and a pillar of Kurdish identity. But for 45 years prior to this, the eviction plans had been haunting Eskîfê.

The Ilısu Dam is one of the 22 dams that the Turkish state aimed to build with the GAP project. The Güneydoğu Anadolu Projesi, or Southeastern Anatolia Project, was launched in the 1970s as a massive state-led development project, vowing for the irrigation of arid land and wider socio-economic development of the region. The water project covers eight predominantly Kurdish provinces: Adıyaman, Batman, Diyarbakır, Gaziantep, Mardin, Şanlıurfa, Siirt and Şırnak. The dams and hydroelectric power plants are built in the basins on the Euphrates and Tigris river that irrigate much of the region before flowing into Iraq and Syria.

Turkish president Erdoğan consistently highlighted the “beneficial” nature of the water project. Proposed to only last 60 years, GAP is a revitalisation of the “abandoned” region under the banner of progress, reminiscent of la mission civilisatrice. However, if Turkey draws a romantic picture of the GAP project, we should remember that their story represents only a fraction of this dream. The flooding of the old town has led to mass displacement of the population, the destruction of land, crops and homes, and memories of what once was. These acts of state violence, which meet the threshold of cultural genocide and environmental racism, were efforts to absorb a predominantly Kurdish territory into the state-grid, within the reach of the state’s arms and control. As a continuation of these efforts, the government built “New Eskîfê” (Yeni Hasankeyf). The new town is located merely two kilometers from the ancient site and holds eight of the original monuments from Eskîfê, all of religious nature, meticulously curated by Erdoğan’s government, transported from “Old Eskîfê” to the New. It also encompasses 710 houses which are intended to accommodate to not even half of the town’s residents: all identical, appearing soulless and always overlooking what once existed.

The title of this piece was inspired by a chapter of Mark Fisher’s book, Ghosts of my Life: Writings on Depression, Hauntology and Lost Futures (2014), a publication in which he lays out the notion of hauntology. Fisher defines hauntology as a confrontation with a cultural impasse, of the failure of the future to set in. As part of this phenomenon, the future functions as a distant agent of virtuality – that which already impinges on the present without physically existing – and as such, is experienced as a ghost.

The theory grasps the long anticipation of the destruction of Eskîfê by the inhabitants of the region, which stretched over many generations and stood above them like a cloud of impending doom, haunting them. While the flooding of the site has only recently been accomplished, the plans for its destruction have been announced since 1975, with many governments promising to complete it. hauntology can be observed here as the forces which act at a distance – it is that which has not yet happened, does not yet physically exist, but has already caused effects.

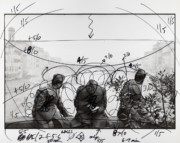

In their photography of Eskîfê and the GAP project, both Carolyn Drake and Emin Özmen, who documented the town through several phases, visually illustrate the absence and traces of this failed future. The images, the spaces, are stained by time, and show how Eskîfê had become the site for an encounter with broken temporality, a fatal repetition.

The women as seen in the image above, taken in 2008 in the outskirts of Eskîfê, are set in a moment in which life seems to be passing but time is not. The different positions and postures, in which one woman is gazing absently away from the camera, another walking straight ahead, seemingly unaware of the rest of the scenery, and the group of women at the centre of the image — the simultaneity of it all — visually translate the temporal standstill. It appears as if they are waiting for the yet to be: that which is unable to arrive, but whose shadow is visibly present.

Fisher differentiates hauntology from nostalgia, stating that what blocks these impressions from being period pieces, or catalysts for remembering, is the clear disavowal of any explicit reference to the past or any recognisable symbol of time or space. Instead, quoting Frederic Jameson, they convey a “waning of historicity”: this brings home “the enormity of a situation in which we seem incapable of fashioning representations of our own current experience.’’ Instead of going backwards and forwards in time, it is about time breaking in.

The Eskîfê community’s long anticipation of their destruction was continuously exacerbated by delays to the project: European investors, who were worried about human rights violations, withdrew from it in 2002, but it resumed four years later. In his written piece of 2018 on the drowning of Eskîfê, Özmen discusses the residents’ experience. “When I mention the old town’s fate they seem rather resigned, ready to leave. They are sad, but do not seem angry. They do not dwell on the subject.” HasankeyfKoord is a local initiative to keep Eskîfê alive. A Kurdish activist working for the group, interviewed for this piece, expressed a similar sentiment: “If you tell a population for decades on end that you will ruin their homes and land, when that moment finally arrives, they will simply accept. It is a way of putting an end to the not-knowing of their fate and suspension of their lives.”

The seemingly abandoned scenery, depicted in Özmen’s image above, visually marks that impending destruction which lurks around the corner. The illusion of space in this picture does not engender a sense of place; the colour of the blue drapes projected on the still water, with many shadows beleaguering it, animate an aura of a ghost house, of being haunted. The sun that is slipping through behind the white curtain resembles a window, appearing as an escape route from a no man’s land, which never moves or changes, which never grows older. The mountain in the background that peeps through is like outer space coming in: breaking in, yet not. Like the future that has not yet set in.

The distinction between past and present is breaking down. This decay has contributed to the impression that linear development has given way to a strange simultaneity, where the current moment no longer exists nor can it be articulated. The photographs refer to the destruction of Eskîfê, rather than depict it. Through a unique visual language, they convey that which is not present, signalling remnants and residues. The drawing of Eskîfê, to which our eyes are immediately guided, stands as the only identifiable thing in the image, announcing a relation to and an anticipation of something which has not yet arrived but is seemingly felt.

The eradication of the site, completed last year, brought a final end to the dooming of the future, and turned Eskîfê into a memory, thus allowing the beginning of the mourning process of a home to thousands of Mhallami Arabs and Kurds, who are once again left without their land.

Rojda Yavuz is a visual researcher and writer. They are a recent MA graduate from SOAS, University of London in the field of Cultural and Gender Studies. Their interests include the body, sexuality, gender, and psychoanalysis, and how these topics intersect. As an extension of their research interests, they delve into archives and revive Kurdish marks and memories, which they share on their Instagram: find them at @r.ojeee.

This project was made possible thanks to support from The National Lottery Heritage Fund.