Sohrab Hura and the Shape of Water

The photographer on the influence of Bruce Lee, and the importance of flexibility to his photographic approach

In this instalment of the ongoing series looking at Magnum photographers’ non-photographic sources of inspiration, Colin Pantall discusses the influence of an interest in martial arts on Sohrab Hura’s approach to his work, the importance of flexibility in photographic approach, and the risks of finding a ‘style’.

“Don’t get set into one form, adapt it and build your own, and let it grow, be like water. Empty your mind, be formless, shapeless — like water. Now you put water in a cup, it becomes the cup; You put water into a bottle it becomes the bottle; You put it in a teapot it becomes the teapot. Now water can flow, or it can crash. Be water, my friend.”

— Bruce Lee

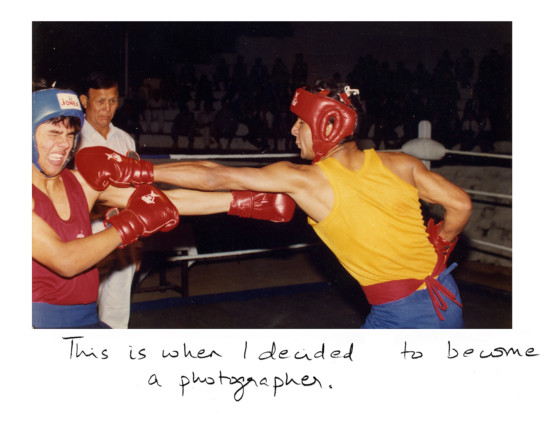

“I love martial arts,” Sohrab Hura tells me via a WhatsApp interview from his home on the outskirts of Delhi. “There’s a pleasure and a rhythm of movement. Martial arts is being one with yourself, like how walking is finding a balance within yourself and being aware of where you exist in the context of the world.”

In photography terms, the fluidity that Bruce Lee talks about is a photographic unknowing, it’s the opposite of finding a voice and a style and a format when you photograph. It’s about shaking yourself out of the visual habits that define you and becoming one with the environment you find yourself in.

“In my case it’s not about the physical, it’s about existing without any structures at all,” says Hura. “Bruce Lee was trying to propose something new within fixed physical structures – he was trying to make a new hybrid martial art by combining all the best parts from other martial arts to create Jeet Kune Do, what Lee called “the art of fighting without fighting.”

“Bruce Lee and the idea of ‘taking the shape of water’ is one of those points that has affected the way I see photography. I’m self-taught, I get inspired, I learn, I unlearn. Each work needs to follow the situation, the space, the purpose. It needs to fill the vessel. I work organically and go into that space.”

This is a view which runs counter to what is often taught in photography. There is the idea that to be a successful photographer you have to find your voice, your style, your theme, your format and stick to it. To define, and be defined by it.

The problem with this approach is that it can become predictable, both for the viewer and for the photographer. There’s a passage in Jean-Paul Sartre’s existential brick-book, Being and Nothingness, where the author describes a waiter who carries his towel just-so, who is attentive, who does all the things a waiter should do. He is the perfect waiter. Except, of course, he is not. He is a man who has the freedom to spill the wine on obnoxious customers, to spit in the soup, to walk away from the job. His pretence at being a perfect waiter is a performance in Bad Faith, a loss-of-freedom that is untrue to his authentic conscious self.

"I’m only on a reconnaissance until the work is over. That way of working releases the pressure and opens something more sensory... The detachment from photographyis what I’m looking for"

- Sohrab Hura

The same idea can be applied to photographers. Wear that Leica too heavily, start believing in your own legend, fetishize your style and you become the photographic equivalent of Sartre’s waiter, a caricature of a photographer who does the things that photographers do because those are the things that photographers do.

Hura is aware of this photographic bad faith on a personal level, and seeks out ways to break away from engrained habits. “It’s about when you hit a roadblock and you need a change,” he says. “What is wrong, what works? There will always be a resistance to the change, both from outside and within yourself, and that’s what happens when I try to find something new. I struggle with that. The question I ask myself is: how do I become water?”

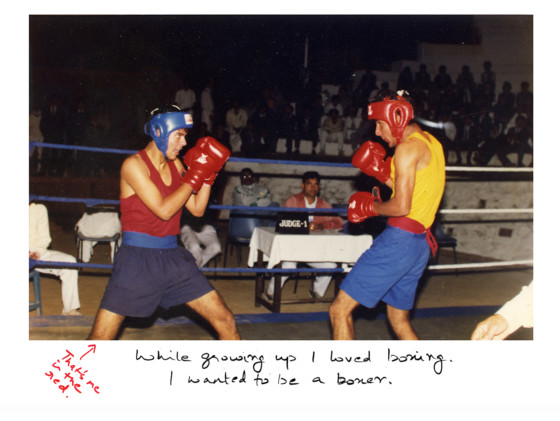

It wasn’t always that way. “For me photography started when my mum wasn’t well and my dad gave me a camera and I went to the mountains. I was 17, because of my mum and everything else happening around me I had difficulties with my education and I felt like I had lost everything. I took 10-15 rolls and took them to the lab and the shop said, “did you take these?” and I said yes. They said “they are beautiful” and that made me feel like I existed.”

The pressure to photograph in a particular way began in 2005 when Hura was photographing people on work schemes in impoverished villages as an extension ofhis university studies. At the same time as making this more documentary based work, he was also making poetic images of a river for therapy.

“I had two streams of work and I didn’t know what I was doing,” he says. “External voices said, pick one stream, it has to be one for authorship. Yet both were part of me. I left the work in the villages more because of privilege – I was going to people whose lives were hard, whose kids were dying, I was photographing them and then going off back to the city, to my safe space where I’d go out in the eveningto have drinks with my friends. So I gave that side up.”

"I don’t think in terms of photography. I think in terms of images... Images are larger than photography. Photography can be limiting"

- Sohrab Hura

Today, Hura regards the work he made in the villages as an example of politically influenced propaganda – although cherished one – a story that fits a predetermined agenda and meets particular visual needs. This frustration of needing to fit into preconceived ideas of a story continued during Hura’s brief dalliance with international media. “I wrote to an editor once. I showed her my pictures and she said this is great, but you’re photographing the wrong issues. I need something new. Can you do a story on India Shining or Bollywood. Someone else looked at my pictures (from his book Life is Elsewhere) and told me to make them look ‘more Indian’.”

This was frustrating for Hura, a photographer whose visual thinking extends beyond the still image. “I don’t think in terms of photography. I think in terms of images, images can be still moving, they can include text, they can be sculptural, they can flow. Images are larger than photography. Photography can be limiting. That’s what I hate about it. So when I discovered Bruce Lee it made me comfortable with the multiplicity of forms of photography. It suddenly made sense that I existed differently in different contexts.”

“There’s the idea of the possibility of photography being an anti-language,” says Hura, “but an anti-language is just another language. The question is how to get rid of all the languages. I think the best way to do that is to embrace them all, break down the hierarchy.”

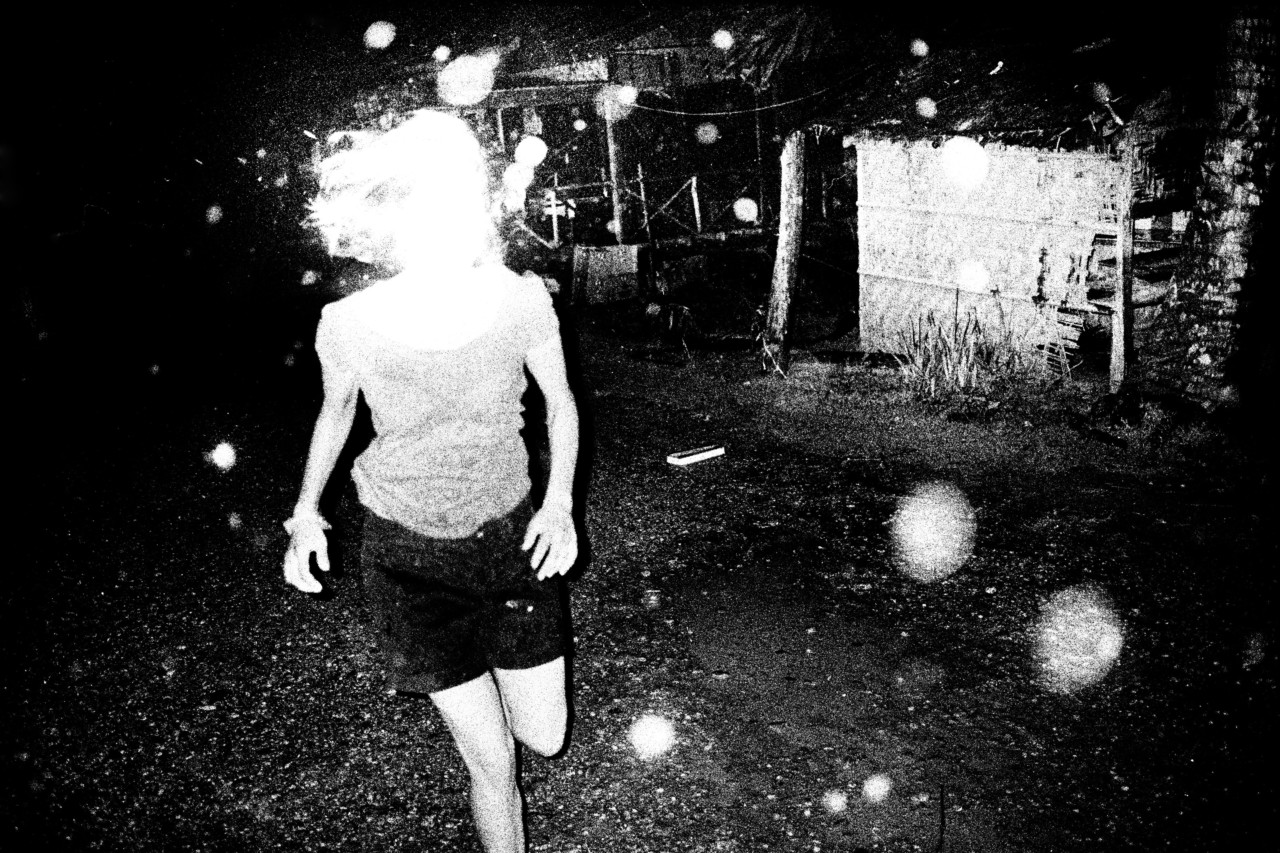

What this means in effect is a kind of photographic fluidity, with Hura making himself like Bruce Lee’s water in order to fit into wherever he is photographing, to make images that will affect the viewer in some way; that emotional affect is what drives his visual narrative. Hura built a complex emotional narrative in both his latest book, The Coast, and in an ongoing body of work he is making in Kashmir.

“The way I work is that something triggers, then I dig a little deeper. When I went to Kashmir I experienced something powerful and I felt this sense of love. That’s one trigger. Then, being Indian, it feels uncomfortable because something isn’t right, because I feel like an outsider, because it’s in this militarised zone and there is this state presence marked on the landscape. So that feeling became another trigger. So I went back and I wanted to find a pulse of what the places mean to me as an outsiderand that can become a trigger for others. I’m simply existing there and taking pictures convincing myself that I’m only on a reconnaissance until the work is over. That way of working releases the pressure and opens something more sensory. If you’re simply making ‘a project’ you end up searching for things but you’re not really looking at them. The detachment from photographyis what I’m looking for, only also that I can enter that space further.”

“I need to break myself down and then build myself up again,” says Hura. “The more detached I am, the freer I feel. It gives me more starting points. If I’m always doing the same work it is too mechanical. My process is about breaking myself from my past. I enjoy it when I’m nervous or scared. It gives me a mechanism to break myself down and invest myself in that work.”