Paying it Forward: Stuart Franklin on teaching the next generation of photographers

The Magnum photographer, author and educator explains what there is to gain from studying photography, and offers an insight into his own compulsion to produce work

The urge to document their world photographically is a drive that has undoubtedly been felt by many Magnum photographers; and it’s a practice that Stuart Franklin explores in his 2016 book The Documentary Impulse, charting the motivation to visually tell stories and represent the world far back beyond the invention of the camera, all the way to cave painting. From pre-history onwards he explores a history of photographic representation in visual culture and many of the practical and ethical issues that form the backdrop to the current landscape of the industry. Through teaching, Franklin aims to help a new generation of photographers go beyond the practicalities of technique and understand their practice within the weight of this context. Here, Franklin discusses what there is to gain from a photography education, and explains how he experienced the ‘documentary impulse’ himself.

On a personal level, how have you felt or experienced the ‘impulse’ in your own practice?

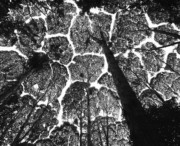

An impulse or obsession is almost crucial to a life in documentary. I have explored a number of ideas – still working on some today – with an irrational drive, where work that I’m pursuing, and the way I’m doing it, makes absolutely no economic sense. Most of my books evolve in that way: Footprint, The Time of Trees, Narcissus, La Città Dinamica – even The Documentary Impulse. I work on projects because I am impelled to do so.

"In visual storytelling coherence across a body of work is an essential part of authorship"

- Stuart Franklin

When you’re teaching students about documentary photography, what is the most common thing you find lacking in their knowledge?

That’s a hard one. Photography is technically quite straightforward to at least get acceptable results. All normally looks fine except the organization of the picture space – composition. Often the problem is the subject caught in the middle of the frame with little regard for the picture space as a whole. Outside the technical, there are huge gaps in seeing their work in the context of the history of photography, or art, and confusions about what is being attempted. Finally, there are often problems with visual coherence: ten pictures that look like they’ve been taken by ten different photographers. In visual storytelling coherence across a body of work is an essential part of authorship.

Your book The Documentary Impulse explores the history of visual documentation since pre-cameras, all the way back to cave paintings. How important is it that a photographer knows about the historical context of their practice?

Deep knowledge of the history of art and photography is, in my view, very helpful. Take just one element – color. Color is complicated and confusing but when we see how different artists have worked with color to create balance or the lack of it, we can learn from this. Look closely at Rembrandt’s portraits in London’s National Gallery, or Whistler’s portrait of his mother in Paris’s Musée d’Orsay, or Frank Auerbach’s paintings of Mornington Crescent in the Courtauld Gallery, also in London. There, we see how even a restricted palette can be effective. Then look at Luigi Ghirri’s photographs in the Po Valley, or Alec Soth’s in the Mississippi and you start to see the connections, you can see how certain combinations work and add a psychological force.

"We have to examine our own instincts and keep on track"

- Stuart Franklin

What are the main things that a documentary photographer should keep in their mind when they are working?

Avoiding stereotypes or pre-texts when engaging with a subject. Keep fresh eyes. Although a background knowledge of the medium is helpful, as I’ve said, what is essential is to be honest to one’s own instincts – one’s own way of telling a story, one’s own passions and motivations. Why am I here? That’s a good question to ask. If the answer is “because everyone else is, or because a well-known/successful photographer is” that’s not a good answer. We have to examine our own instincts and keep on track.

How should a documentary photographer approach their storytelling, and how can they work out whether still photography is the best medium for the story they want to explore?

That’s a good question. Of course radio programs are still broadcast about art exhibitions, and other apparent mismatches that work counterintuitively; but there are some subjects which certain students seek to resolve through still photography that shout out for sound or moving image. Photography’s strength, but also sometimes its weakness, is its ambiguity. Photographs, as others have spelt out, have no past and often no context. They leave gaps for us to fill in, just as ancient Chinese and Japanese poems did (there are literary terms to describe this). If you are comfortable working like this, like a Chinese Song Dynasty poet, then photography is probably the right solution for any subject; because like much in art it has the power to be psychologically affective by being vague or analogous. But if you want to be didactic, tell someone how it is exactly, preach or teach, then film is often worth considering. Look at Ken Loach.

As an established photographer, why do you think it is important to impart some of what you’ve learned over the course of your career to others who may be just starting out on theirs?

I love teaching. I don’t see it as a one-way street where I impart knowledge. It’s a two-way street. I learn as much from my students as they learn from me. Teaching is always a shared discussion, a dialogue about resolving challenges.

Stuart Franklin is teaching on the Intensive Documentary Photography Course with London College of Communication and Magnum Photos. More information about this course, including details on how to apply can be found here.