Susan Meiselas on Imagination and Photographic Education

The photographer discusses her new book, a photographic resource for kids, Eyes Open, and the original 1970s publication that inspired it

Eyes Open: 23 Photography Projects for Curious Kids by Susan Meiselas is available to buy on the Magnum Shop here.

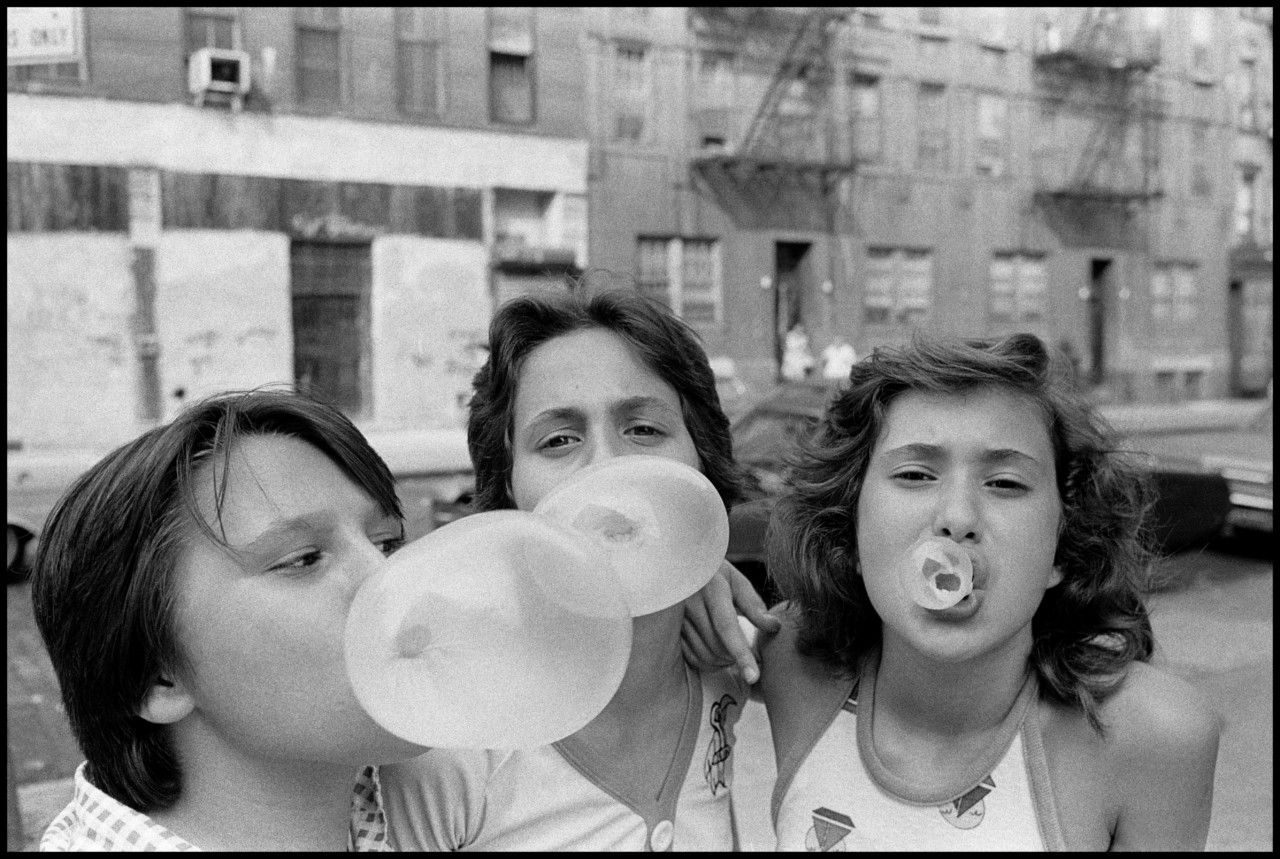

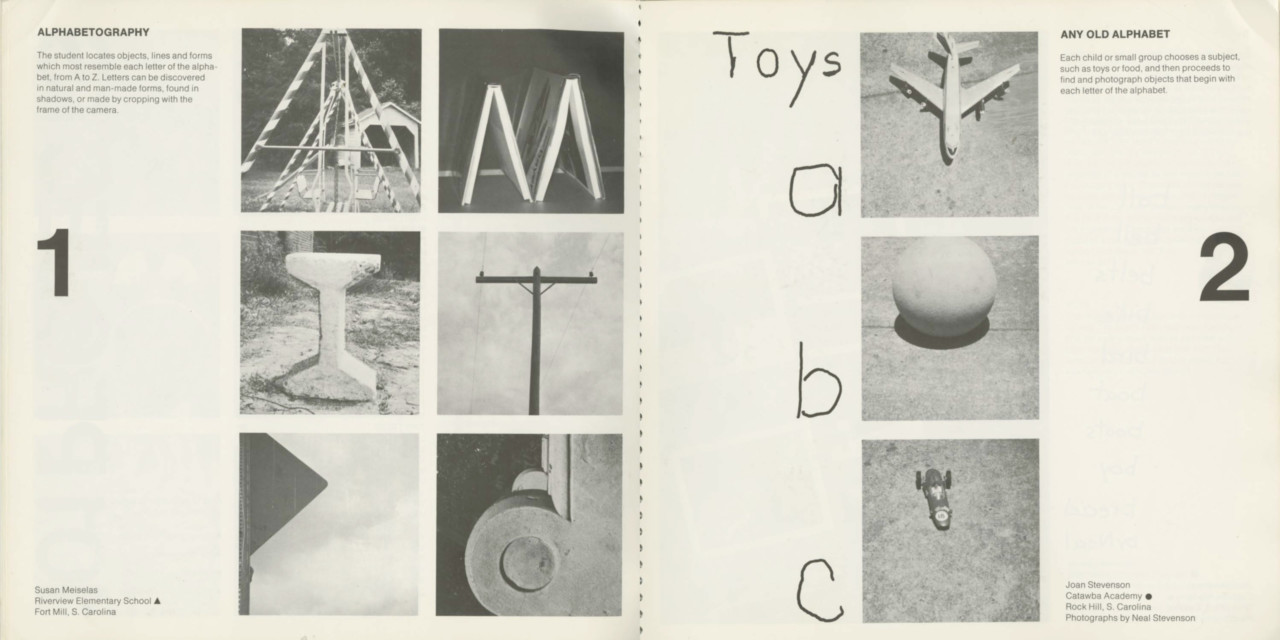

“When you make something up from so many multiple parts, it takes a long time to feel its wholeness.” As Susan Meiselas flips through her newly published photography sourcebook for children, Eyes Open, she adds, “Here I am, holding this object that has decades behind it.” Produced in collaboration with Aperture, Eyes Open: 23 Photography Projects for Curious Kids (2021) comes nearly fifty years after Meiselas’ Learn to See (1974), a beloved sourcebook of ideas published by the Polaroid Foundation when Meiselas was a teacher in New York’s South Bronx.

“Back then, I didn’t think of myself as a photographer; I wouldn’t even have said that I taught photography,” explains Meiselas. “I was using photography with the idea of stimulating kids to learn to write and read their own words.” With her students, Meiselas made pinhole cameras out of shoeboxes, and, eventually, even a darkroom.

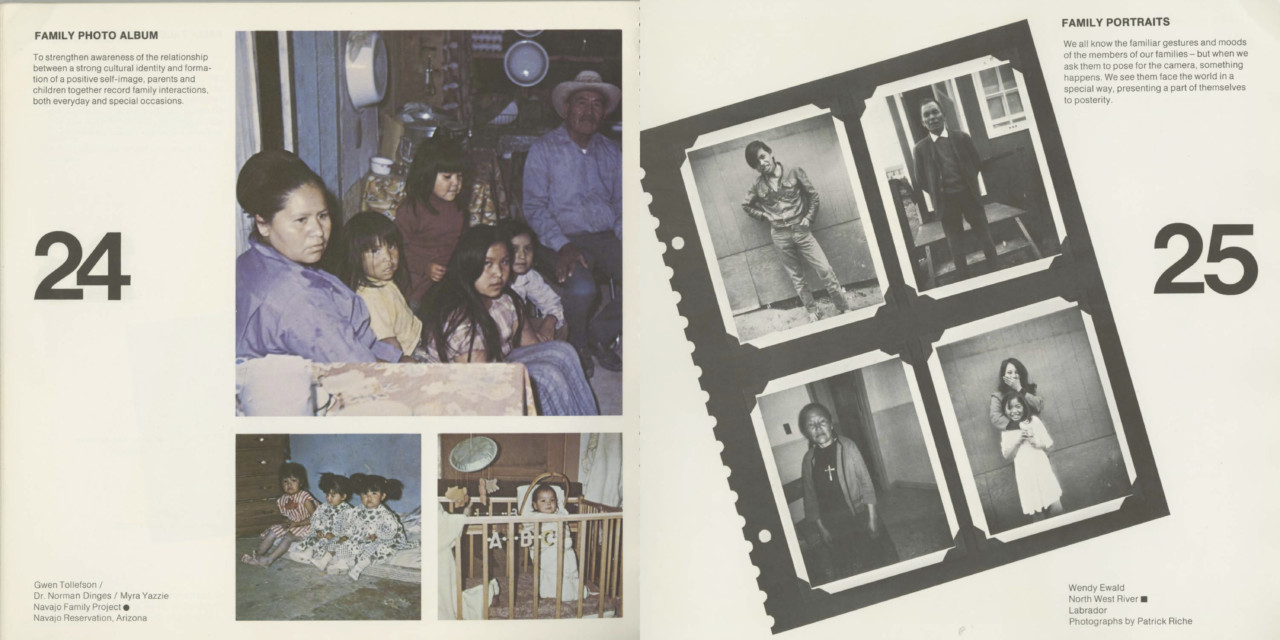

After becoming one of the beneficiaries of the Polaroid Foundation’s program granting cameras and materials to schools, Meiselas wasn’t sure how to best utilize the new equipment. So she reached out to Polaroid, asking them for the contact information of other teachers they had given equipment to. After receiving a list of a hundred teachers, she wrote to each of them. “My instinct was to write: I’m just curious, what are you guys doing? Would you share your project and approach? Let’s figure out together what’s possible.” The correspondence with the teachers led to the making of Learn to See.

When Aperture invited Meiselas to rethink Learn to See, she knew that a facsimile would not work. Her first sourcebook came in a radically different time. “Everything about photography has changed. Now we’re considered entirely visually literate, and everyone’s an image-maker.”

Much like its predecessor, Eyes Open evolved over time through an outreach initiative that brought together people engaged in teaching photography in a classroom or an after-school program. Over 200 teachers from around the world gathered and shared work from over 400 children. “This community of responders informed what the book is and inspired what it could be,” says Meiselas.

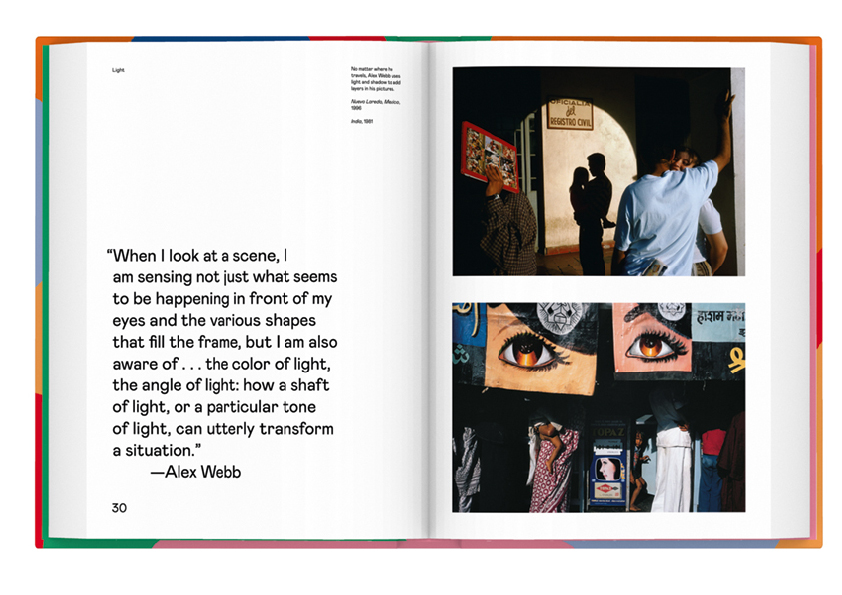

In making the new book, Meiselas decided to expand on the projects in Learn to See. The concept that emerged was to interweave photographs by children with images and quotes from artists. “I knew that the projects of the kids alone weren’t quite enough in the world that we’re living in today. Also, artists’ images weren’t enough. I had to include the ideas that generate these images.” The artists included in the book have a diverse set of approaches to imagemaking. Among them are Dawoud Bey, Alex Webb, LaToya Ruby Frazier, Jim Goldberg, Wendy Red Star, Graciela Iturbide, Yael Martinez, and Cindy Sherman.

One of Meiselas’ favorite quotes in the book is from Zoe Leonard. “It’s how you are looking, as much as what you’re looking at.” That quote is followed by a section titled Reframe in which Saul Leiter’s quote, “I like it when one is not certain what one sees,” is noted. After Leiter, the reader encounters a Rinko Kawauchi quote, “I want imagination in the photographs I take.” Meiselas took time to weave the quotes into an ethos. In her view, “If you start to read the book through the quotes, the ideas in these quotes start to become important. You see how, yes, it’s about light, and, yes, it’s about a frame. Still, it also starts to be about ways of thinking.” She hopes that the book will inspire a change in the experience of image-making “from a pragmatic exercise into a more conscious processing.”

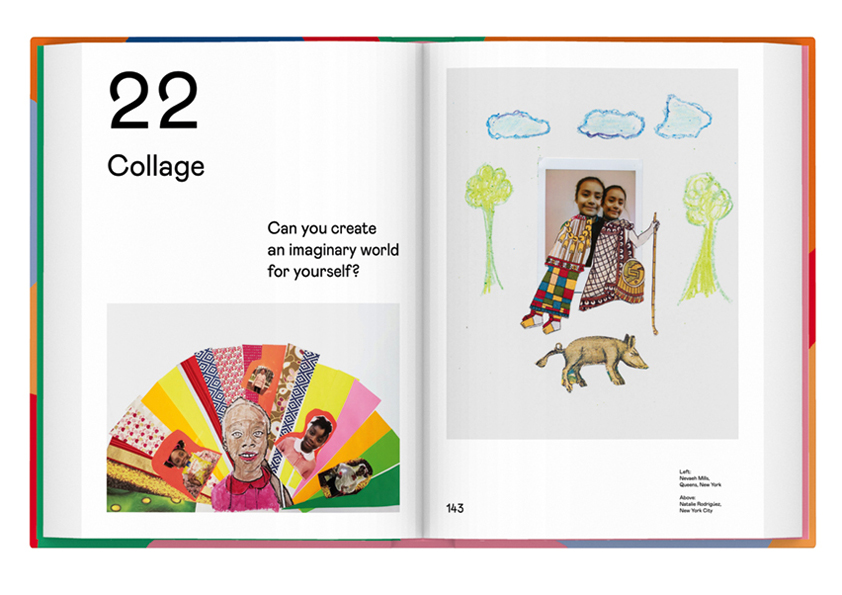

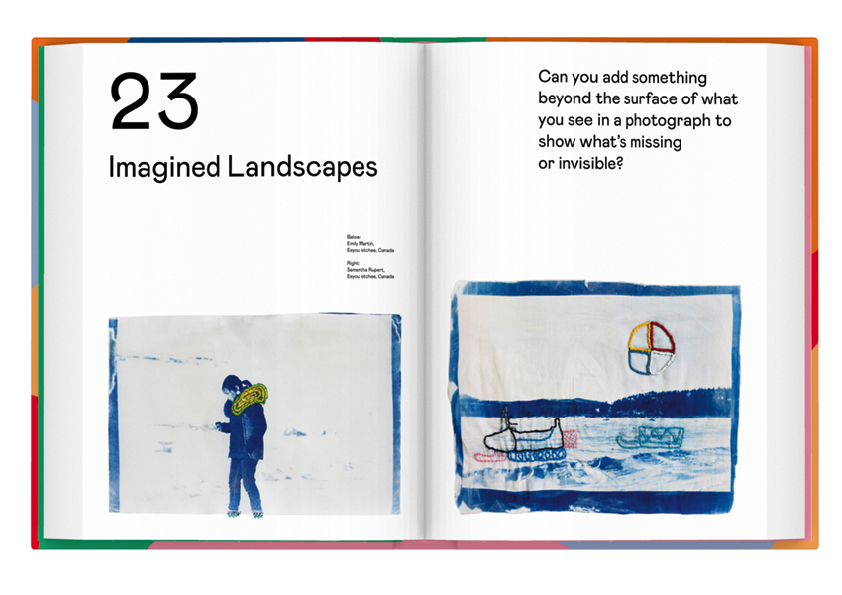

The task of initiating such thinking is left to the twenty-three projects by fifty-one students from around the world and thirty-three artists and photographers that were included in the 160-page book. The featured projects are concerned with strategies, themes, and concepts such as portraits in disguise, light, imagined landscapes, and collage. These projects are envisioned as ‘prompts,’ simple but potent ideas that aim to inspire and engage children, aged nine and older, to express themselves, explore the world, and “imagine beyond what’s in front of you,” writes Meiselas in the opening of the book, titled An Invitation.

“The culture of the iPhone has generated a self-orientation versus an outward-looking, engaged process of observation, which is something that I still value.” However, she explains that the book isn’t arguing against taking a selfie. “The self is a centering point from which to begin. From there, where do you travel to? Where is the opportunity for something beyond what you see to what more you can imagine?”

One of the possible paths is indicated in the work of Wendy Red Star, whose annotated image, “Long Horse, Sits in the Middle of the Land, and White Calf” from the 1873 Peace Delegation series, is included in the Me section. To Meiselas, Wendy Red Star was an obvious choice when thinking about who can contribute with other ways of going beyond the image, so that the image can be decoded, re-encoded, re-imagined. For Meiselas, “Wendy Red Star is not only relating to her very specific tribal history, she is also opening up for others to potentially think about what they would like to know in the future about the past.”

Whether the children will take on such ideas and strategies is unclear. “I haven’t yet experienced this book in the hands of those who it was made for, to see to what extent they engage with it and get excited and then go beyond it,” she says. Meiselas’ first interaction with children about the book came while co-facilitating a Whitney Kids Art session. Together with an arts educator, she chose ten paintings from the museum’s collection that had elements of what children could find in their homes and then invited them to mimic these paintings, which is one of the ‘prompts’ in the book.

In the first stage, children were supposed to find a place in the apartment that resembled the setting in the painting. In the second, they were supposed to observe the person in the painting, noting how they were dressed. “So, the children were racing around, scrambling to see if they could find a yellow scarf or a blue blanket or whatever to come back to the screen with,” explained Meiselas. In the final stage, children were encouraged to look at the person’s gestures in the painting and mimic them in the photograph they would then take. “It was exciting to see how it just invigorated their imagination.”

Meiselas’ work and words open and close the book. Although not presented as ‘prompts,’ they do exactly that. She asks the readers to think about who they are taking the picture for, what they are sharing, and what they are giving back. “That is what I always ask myself,” she writes. Irrespective of whether photography can change the world, Meiselas is confident that it can change the photographer, which is why she concludes with, “Just open your eyes!”