Susan Meiselas and Matt Black on Being the Mentors They Wanted to Have

Ahead of their upcoming long-term mentorship program, Susan Meiselas and Matt Black discuss the importance of photographic feedback and guidance

On Susan Meiselas and Matt Black’s long term mentorship program starting this fall, develop your personal or editorial projects with guidance from the photographers, while gaining support and feedback from peers, over the course of seven months. Learn more here.

When experienced photographers mentor up and coming artists, they are typically inspired by the mentors who helped them early in their careers. Maybe they had a great teacher they want to emulate, or they received some useful advice they want to pass along to others. Photographers Matt Black and Susan Meiselas, however, bring a different perspective to the Magnum’s long-term mentorship program. Neither Black nor Meiselas had a mentor. They hope to offer other photographers the kind of encouragement and feedback they wish they had received when they began working on long-term photo projects. “Thinking back, there were times when a word or two from people I admired would have meant a lot,” Black recalls.

"[I want to help photographers] to find that inner voice or personal perspective, rather than [take] photos that people expect [them] to take."

- Matt Black

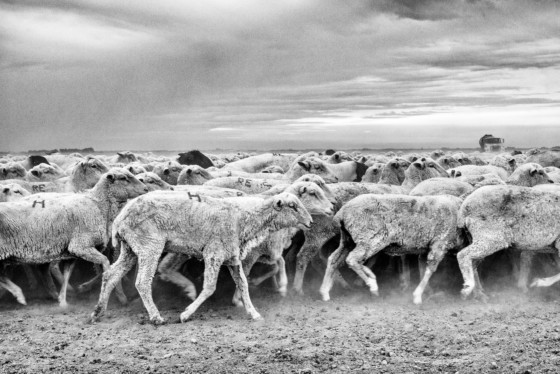

Black grew up in the rural farm area of California’s Central Valley. “As a young photographer, there was basically zero support.” When he began working for his hometown newspaper, staff photographers shared offered some tips, but amidst the demands of shooting daily assignments, Black says, he was not encouraged to develop a distinctive photographic voice. To hone his style of “authored” photography and pursue the topics that interested him, he says, he had to strike out on his own. In the years since then, Black has produced large bodies of work exploring economic and environmental issues. But “as a young photographer it can be hard to gin up the confidence that what you are doing matters.”

As a mentor, Black says, he hopes to help other photographers “to find that inner voice or personal perspective, rather than taking photos that people expect you to take.”

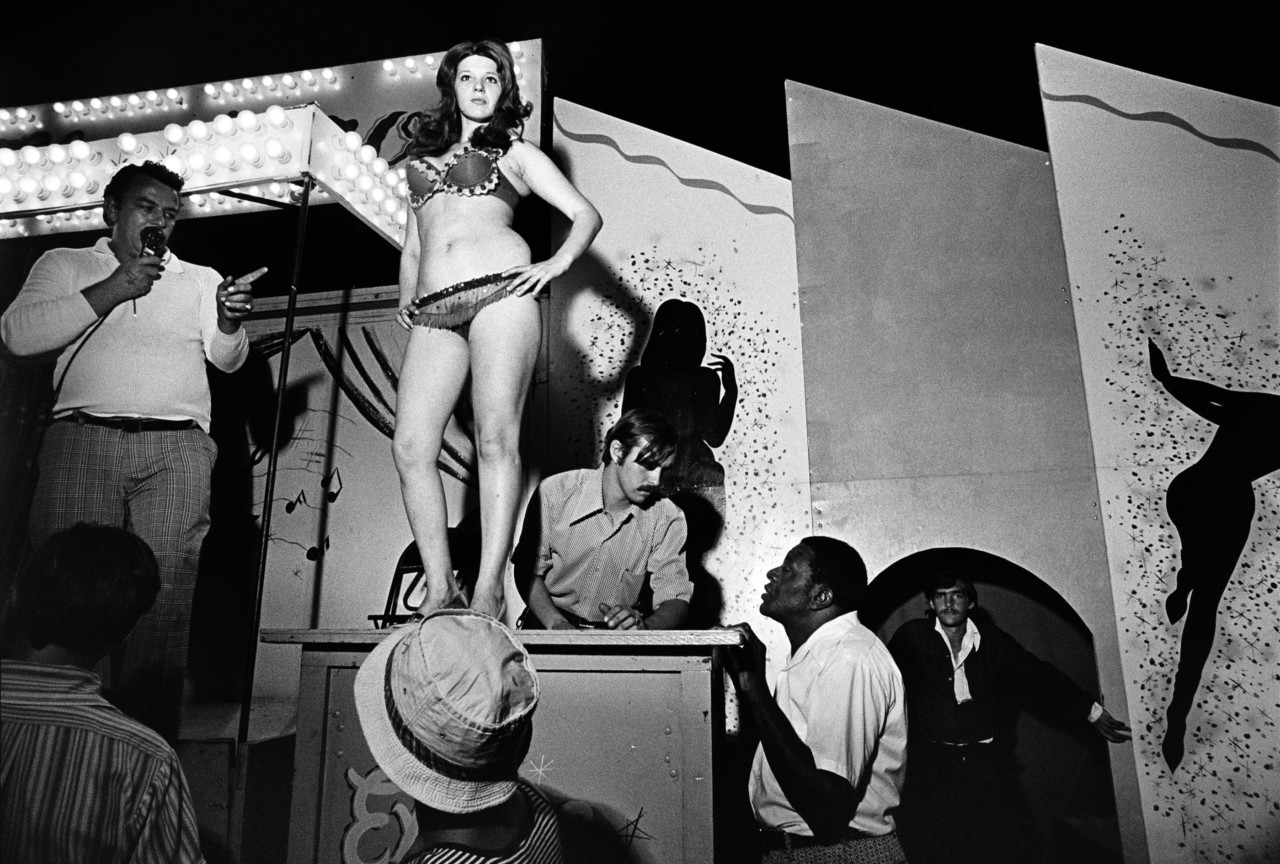

When Meiselas began working as a photographer in the 1970s, she says, “Internships didn’t exist.” Through her graduate work in education at Harvard, she studied with photographer Len Gittleman and the sociologist-turned-documentarian Barbara Norfleet, but had no opportunities to see photographers building careers outside the classroom. Being taught how to take photos is one thing, Meiselas says, “But what do you do with photography, and how do you bring it into your life?”

"If you can create that network around you to get that feedback, that’s invaluable."

- Susan Meiselas

Since then, she has cultivated a network of peers and colleagues she turns to who provide “open, honest, critical and supportive” input and advice. She recently finished work on a project, and has been showing a PDF of the images to a few people, asking them, “Is there something more I could have thought of?” She hopes participants in the mentorship program will continue to support each other long after the mentorship ends. “If you can create a network around you to get real feedback and perspective, that’s invaluable,” she says.

A pioneer in collaborative photo projects, Meiselas has developed some of her most ground-breaking work while embedded within communities—working with photographers in Chile and Nicaragua, as well as co-creating a photographic history of Kurdistan. Meiselas has taught photography classes over decades, and led photo workshops around the world. She describes her teaching as collaborative rather than instructive, as “working alongside students” while fostering “a dialogue” about their goals and ideas. She explains, “I wasn’t teaching people to be me. I wanted to inspire them to be themselves.”

Meiselas looks forward to collaborating with Black during the mentorship program. “I love the passion and intensity Matt brings to his work, which is what we hope to mentor in others,” she says. “What we have in common is allowing ourselves to be taken over by something we become obsessed with.” Meiselas believes that intense curiosity about a topic is essential for photographers who want to embark on long-term projects. “I think if they don’t commit to the work, they won’t be able to survive making work over the long term,” she says. “Such passion can’t be taught”, Meiselas says. But for photographers who have a subject they are eager to explore, Meiselas says she and Black can help them see what they are seeing and understand more deeply what draws them to their subject, to focus on what they want to say and how best to communicate it. Then the question becomes “What form do you want your work to take? Is it best as multimedia? A book? Where do you see the work belonging and who is it for?”

In her mentoring as in her teaching, Meiselas works alongside photographers, rather than leading or instructing them. “They’re making their own discoveries,” she says. “I think that good mentoring is helping people see themselves and who they can become.”

Black agrees. “My goal in teaching is to set people on their own path,” he says. Through the mentoring program, he hopes to encourage photographers to trust their instincts. “This kind of thing offers validation and support, which is hard to come by when you’re just starting,” he says. Remembering how he forged his own path to making documentary work, he hopes the experience he and Meiselas’s share will make the path easier for others. As mentors, he says, “You can part the grass a little bit.”