The Principles That Have Shaped a Photographic Practice

How fundamental convictions underpin the inclusive approach of Susan Meiselas’s photography

In photojournalism, the frontline tends to mean one thing — the area on the edge of some immediate, dangerous action, usually a battleground of some degree, but for Magnum photographer Susan Meiselas, the term refers to something more abstract. For Meiselas, the frontline does not only represent a “geographical space” but, she says “a documentary photographer can cross the line and show that the conflict zone is not just a battleground in a distant land; it is also in our homes, it is self-inflicted, it’s in our heads.”

The American photographer, who joined Magnum in 1976, has spent a prolific career creating work that delves deep into the lives of others, indeed sometimes in battle zones, but often in quieter settings, where her subjects become collaborative forces in making work that represents far more than the resulting series of photographs.

Mediations, a retrospective of Meiselas’ career opens at FOMU Antwerp on February 17, and runs until June 4, 2023. In this article from 2018, we revisit some key moments from her career and the principles that shaped her photographic practice.

For Meiselas, the photograph forms only part of a larger project of documenting and forging connection and understanding. “The photographs are immediate personal encounters that last only a moment,” she says; “These encounters may later create a bridge for constructing larger narratives, which go beyond someone’s personal story to a wider national or cultural history. The picture is then merely the starting point.”Linchpins of community engagement in Meiselas’s photographic storytelling form a collaborative approach that has manifested throughout her work, from strippers in New England to an insurrection in Nicaragua. Looking back over some of the key defining stories of her career for a new book On the Frontline, Meiselas provides an insightful personal commentary on the trajectory of her photographic practice, and offers takeaway considerations for photographers looking to deepen their relationships with the subjects they work with.

"To make a good portrait, you need to reveal a private moment, which can feel like an act of theft."

- Susan Meiselas

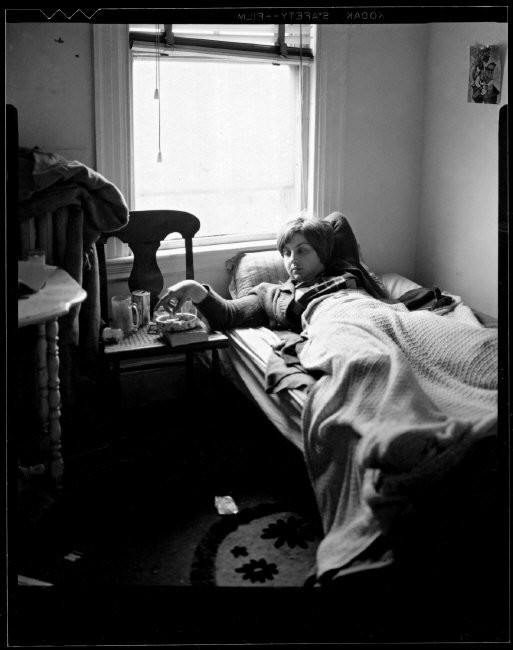

Being photographed

Whilst living in a boarding house in Cambridge, Massachusetts in 1971, Meiselas turned the camera on herself first. The feelings she encountered with the subjects of her photographs would inform her collaborative approach henceforth: “To make a good portrait, you need to reveal a private moment, which can feel like an act of theft”.

“Then there is both the possibility of the construction of the portrait and the capture of a moment. I wanted to place myself in the boarding house because I lived there and was present. At the same time, I felt invisible. That invisibility creates a tension throughout my work. I am present, but I want to avoid the focus on myself. I am not a ‘fly on the wall’: I don’t pretend not to be there, but I am not the ‘story’. I might be the bridge, the guide, and in some sense the collaborator with the subject”.

Creating narrative

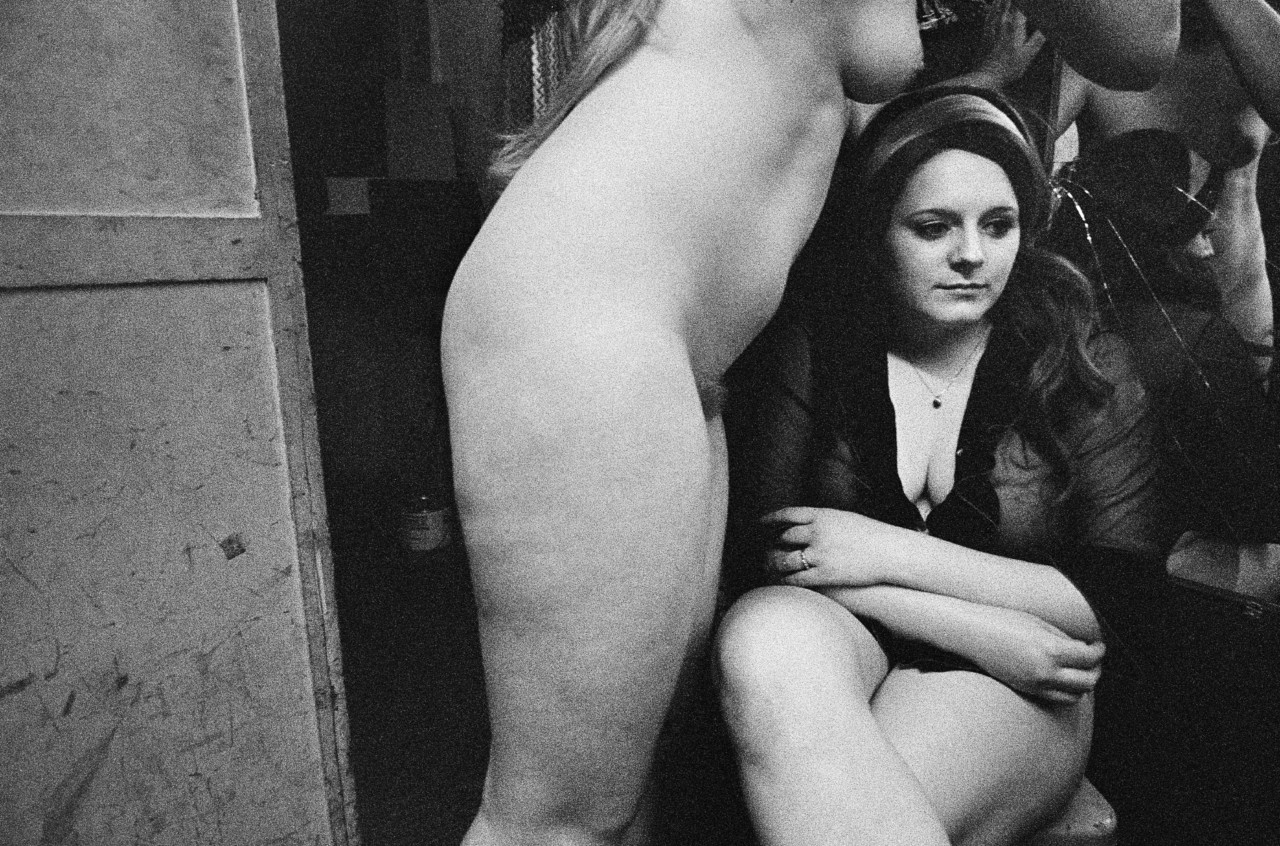

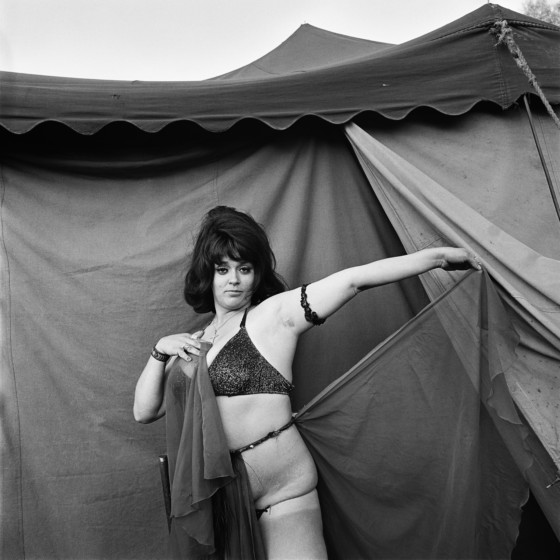

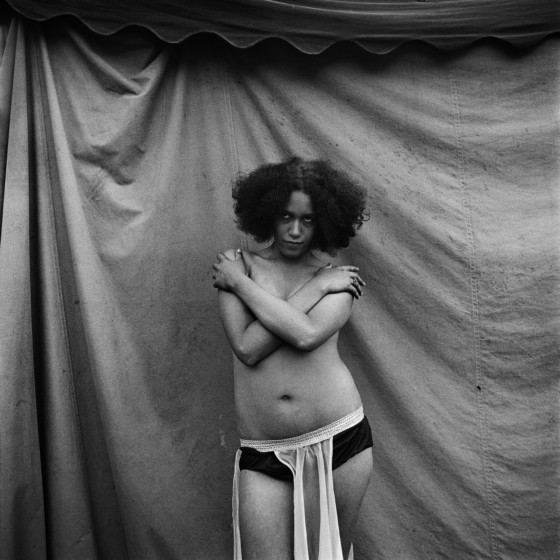

From 1972 to 1975, Meiselas spent summers photographing and interviewing women who performed striptease for small town carnivals in New England, Pennsylvania, and South Carolina. With a collaborative approach that included interviews, she portrayed the dancers on stage and off, photographing their public performances as well as their private lives, along with their managers and the spectators of the show. When it came to displaying the work, the narrative included her images with accompanying sounds of their voices. The book interspersed excerpts of transcribed text throughout her pictures.

“I don’t see myself as an artist just working within a community of artists. I am most interested in the community from which the work actually comes. I resist the cultural label of ‘photojournalism’, which puts one’s work into a box. This work was not assigned or produced for a specific publication, but it was later seen within specific publications, and there lies a great distinction. It was first seen on walls, not printed pages. The women brought me in, and the book later brought a hidden world to public attention, sharing a complex story from the inside out.”

"...a documentary photographer can cross the line and show that the conflict zone is not just a battleground in a distant land; it is also in our homes, it is self-inflicted, it’s in our heads."

- Susan Mieselas

Collaboration

Meiselas sees the act of a photograph as a collaboration that is not completed once the photograph is made, but the relationship between herself and her subject continues long afterward, as she finds creative ways to involve the people she has photographed. In her first work in Massachusetts, she showed the images she made to the subjects in them, and asked how they saw themselves represented in her images. She then displayed their words alongside the portraits in the exhibition. “I was experimenting with how to bring their voice into the work. The subject has to want me to be there for me to feel that I can be there,” she explains.

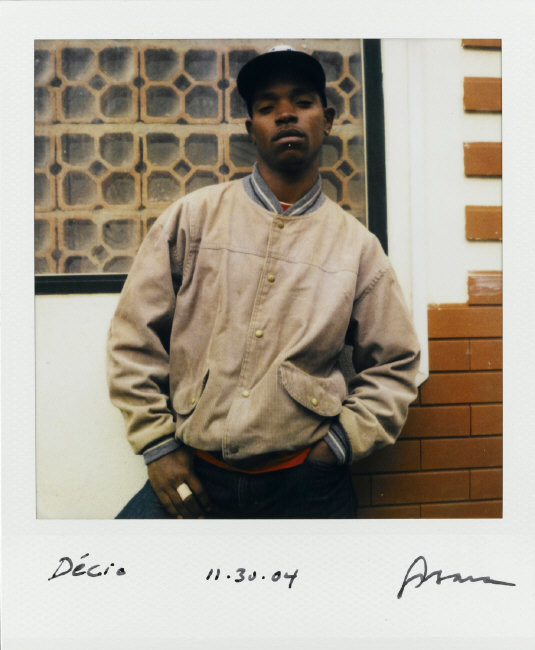

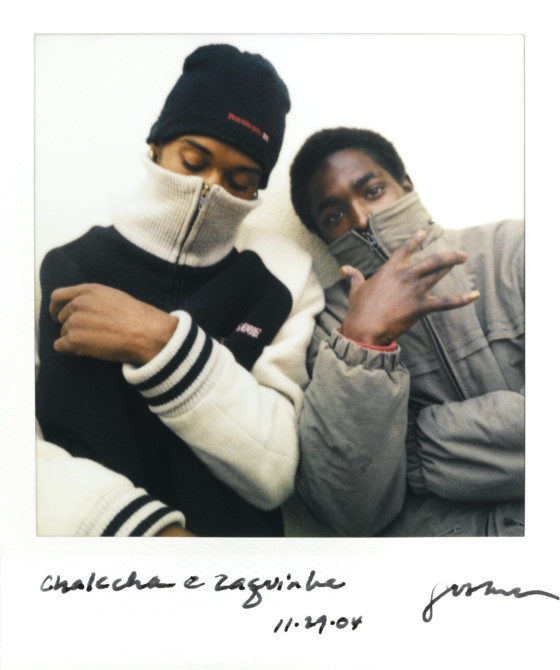

Years later in Cova da Moura, Portugal, when her work was to be shown in Lisbon, she returned to the neighborhood that she had photographed, with a novel way of including her subjects. “I knew that none of the kids would go [downtown]. A museum just didn’t mean anything to them. I felt I had to work on a parallel project with the teenagers to coincide with the museum show.” So Meiselas led a photography workshop, giving them small point-and-shoots to work with, and then installed reproductions of her portraits and their photographs on the streets of their own community.

"The subject has to want me to be there for me to feel that I can be there."

- Susan Meiselas

Returning and Giving back

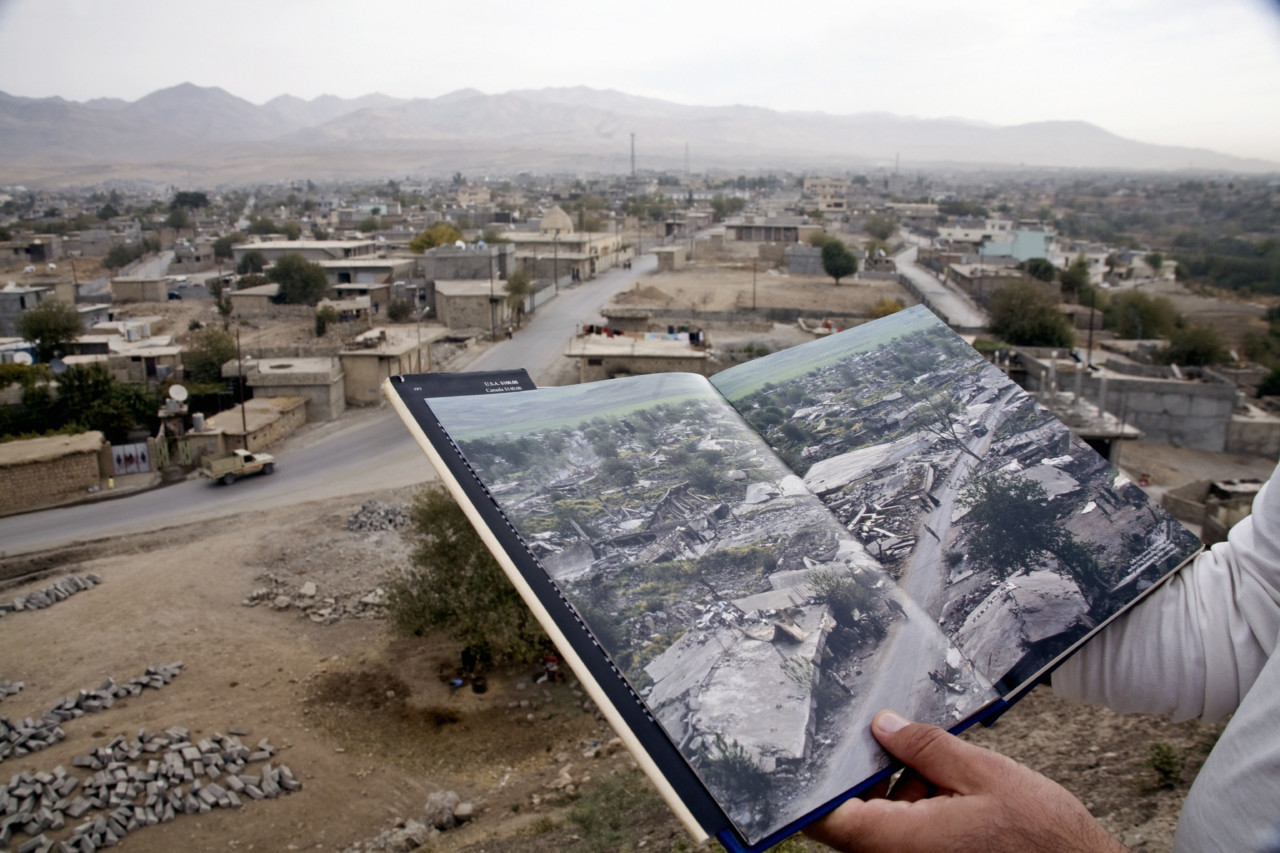

Meiselas first went to Kurdistan to document Saddam Hussein’s Anfal campaign against the Kurdish population in Iraq. She then began working with Kurdish scholars and the community to gather and reproduce photographs from Western archives and family collections to create a visual history, in both book and exhibition form.

The second edition of the book, gave her the opportunity to update another decade of history, and translate sections of the book into Sorani, the Central Kurdish language, and Turkish. However, unfortunately, the books were banned in Turkey so Meiselas wasn’t able to deliver them over the border to Kurdistan. The books were reprinted in Spain and copies were shipped by boat to Dubai where they could be sent as airfreight straight to Kurdistan. There, Meiselas helped to distribute them to libraries, universities, families and all who had contributed.

“A photograph is always a record of a relationship. People had contributed photographs they had made or found and given them to a stranger in the interests of a history that was very precious to them. The cycle of return of what had been generously shared felt complete”.