The Circuit

Bruce Gilden talks to Simon Bainbridge about his new 'family', a community of bikers in New York City known as 'the circuit', who feature in close-up in his latest book.

“I’m known for getting close,” Bruce Gilden once said, “and the older I get, the closer I get.”

The largely self-taught photographer has been doing just that since the late 1960s when he bought his first camera, cutting his teeth on the sidewalks and boulevards of New York City where he was born and bred, establishing himself as one of the true originators in the genre of street photography – and, in particular, the candid portrait.

Gilden is best known for his graphic and often confrontational close-ups made using flash, giving his pictures an intimacy and directness that have become his signature. He’s shot dozens of personal projects and countless commissions, taking him around the world, most notably in Haiti, Japan, India, Russia, France, the UK and Ireland. But, for his latest series, he went much closer to home, photographing bikers in New York, often in the same neighborhoods where he grew up.

Magnum’s Head of Content, Simon Bainbridge, caught up with him via Zoom one morning in early November to find out the story behind the images he’s taken for his new book, The Circuit, published by Dewi Lewis (and now available on the Magnum shop).

Let’s start with the backdrop to these pictures and the context of the Covid epidemic. Like everyone in spring 2020, you were in lockdown. But before we get into that, let me ask you – are you the kind of photographer that always needs to be shooting, even when you’re not working on assignment or a project?

No, no. I don’t believe that the people who carry their camera with them all the time are the best photographers. People like me, or Martin [Parr], we don’t carry our camera unless we’re going out to work!

So how did lockdown disrupt your life, then? What got put on hold? Were you able to handle it? Or did you like the forced change?

Seven years ago we moved Upstate. So, I’m not in New York City. We live in a place called Beacon. It has about 15,000 people. You know, it’s not empty. It’s not in the middle of nowhere. But it’s the middle of nowhere! So, I didn’t really know what to do.

I started to do a series on people wearing masks. I went to places like Walmart, and I would just ask people if I can take their picture while they’re pushing their cart. It was sort of candid, but staged. And it was very interesting to see that most people didn’t give a shit that I wasn’t six feet away from them…. Nobody seemed to mind.

Then came the murder of George Floyd, and the uproar that followed, and you decided to start going into the city with your wife to try and make photographs.

Each time, we had to drive a couple of hours to New York City to go to some protests. Then, one day, I was getting pissed off because we weren’t seeing seeing anything, we drove all the way in, and nothing’s happening. Then, all of a sudden, we came upon Barclays Centre [a large auditorium where the Brooklyn Nets play, and where the plaza outside has become a focal point for protests in the borough] and I heard these motorcycles revving up. I turned the corner; I saw all these motorcycle guys, and I said, “Holy shit! Wow! I have something here!”

"They've accepted us. They call me 'OG', or 'Old Guard' or 'Old Gangster'."

-

What convinced you to pursue ‘the circuit’ as a longterm project?

I have to say that, in the past, in situations where I’ve been near motorcycle club guys – you know, the serious guys – it never ended well. But these people seemed to be very nice. And I just dove right in and started taking pictures.

I didn’t realize there was so many Black motorcyclists in New York City, but now I’ve come to realize there are hundreds of clubs. I mean, if you’re not in certain areas, they’re like, invisible. You don’t see them in Manhattan.

Afterwards [following that first encounter outside Barclays Center], my wife and I reached out to certain sources, and it just snowballed from there. You know, when I went in, I didn’t know anything about ‘one-percenters’, I knew nothing about ‘prospects’. Now, I’m pretty learned about all of this stuff. I know how things work.

"When you go to these places with these people, you leave your troubles outside the door."

-

To what extent did you immerse yourself into the world of these motorcycle clubs?

I’m not a biker, but these people have been great. They’ve accepted us. They call me ‘OG’, or ‘Old Guard’ or ‘Old Gangster’. I’ve been called ‘Fearless’ – well, that’s pretty true but, you know, we have a very good rapport.

And the interesting thing is, they’ve become like my family. It’s more than a photo project. I go to events knowing I’m not going to get any pictures. I just go because we have a good time. Because when you go to these places with these people, you leave your troubles outside the door. Everybody is cool. Everybody is polite. Everybody is respectful.

Do you always have that trigger moment at the beginning of a project, like you had outside Barclays Centre?

My projects are always visual. I find beauty in things that generally people wouldn’t find beautiful. So, to me, that’s the trigger.

This project is color and it’s mostly horizontal. I don’t see portraits [here], and you’ll notice there’s very few motorcycles in there. It’s about the people, not the object, okay? And the reasoning behind that is just because of the way I shoot… generally, closer is always better. I’m not into doing fillers. I always try to get the best shot possible.

"If I feel good, I do it. If I don't feel good, I don't do it. Okay? That's my mantra."

-

It must have been challenging photographing in these tight spaces, especially at this particular time in history, working with some pretty tough people…

During the pandemic we were in clubhouses and we were packed in like sardines in a can [laughing]! I mean, I was 74-years-old at that time, I don’t even know if I was wearing a mask – probably not! And I don’t think most people could shoot in that environment, except someone like me; not because of talent, just because that’s how I see.

For me, if I feel good, I do it. If I don’t feel good, I don’t do it. Okay? That’s my mantra.

In these clubs, especially in the beginning, and even now, you can’t photograph everybody. Not everybody wants to be photographed, okay? You have the one-percenters – that’s sort of like the Hells Angels, The Pagans, The Mongols, and there are a tonne of Black groups that are one-percenters too. So, when I come into a place, I announce myself to certain people. I don’t do as much now because they know me, but I would say, “I’m gonna be taking some pictures. You don’t mind.” I don’t say, “Do you mind?” I say, “You don’t mind.” Okay?

Of course, it doesn’t matter: if they don’t want me to take it, then they don’t want me to take it. But with the one-percenters, you know you can’t do it. Because there’s a hierarchy and rules.

I remember in one of the clubs, n the front of the door they say, “We don’t call 911.” And I have the same mentality: if I have to handle it, I’m going to handle it with you, you know. I’m a physical-type person. So, you know, you give respect, you get respect. And that’s very important.

And also, I don’t change my being in relation to these people. In other words, I’m very comfortable with them. My father was a gangster type. So I know I don’t ask questions.

"We have a good time, all the time. The music is great. The people are fun. But sometimes people test me, and I call them right away."

-

You are a native New Yorker, born in Brooklyn, and you grew up in Queens. So you are familiar with these people and places to some extent?

It’s funny because many clubs are located in Brooklyn in the area where I used to drive a truck, in Brownsville, in East New York, in the tough areas – they’re still the tough areas! So I’m comfortable there.

We have a good time, all the time. The music is great. The people are fun. But sometimes people test me, and I call them right away. I say things to them that I think most people wouldn’t say to them. When I got something to say to you, I say it to you, you know?

It’s obviously a point of pride that you can walk into anywhere and go up to any group of people and not have those preconceptions. Is that a reflection on you being an open person, or is that your life experience, you know, that you’ve lived a life yourself?

Well, it’s a combination of both because, first of all, I think one of my talents is being able to read people, and being able to read situations. Now, if I’m not interested, I close down. If I’m interested, I try to make it happen. I’m very passionate.

And since I want to do something, and I have a good heart about it, and I think I can do it well – then why would you say no to me? So I come in with that attitude.

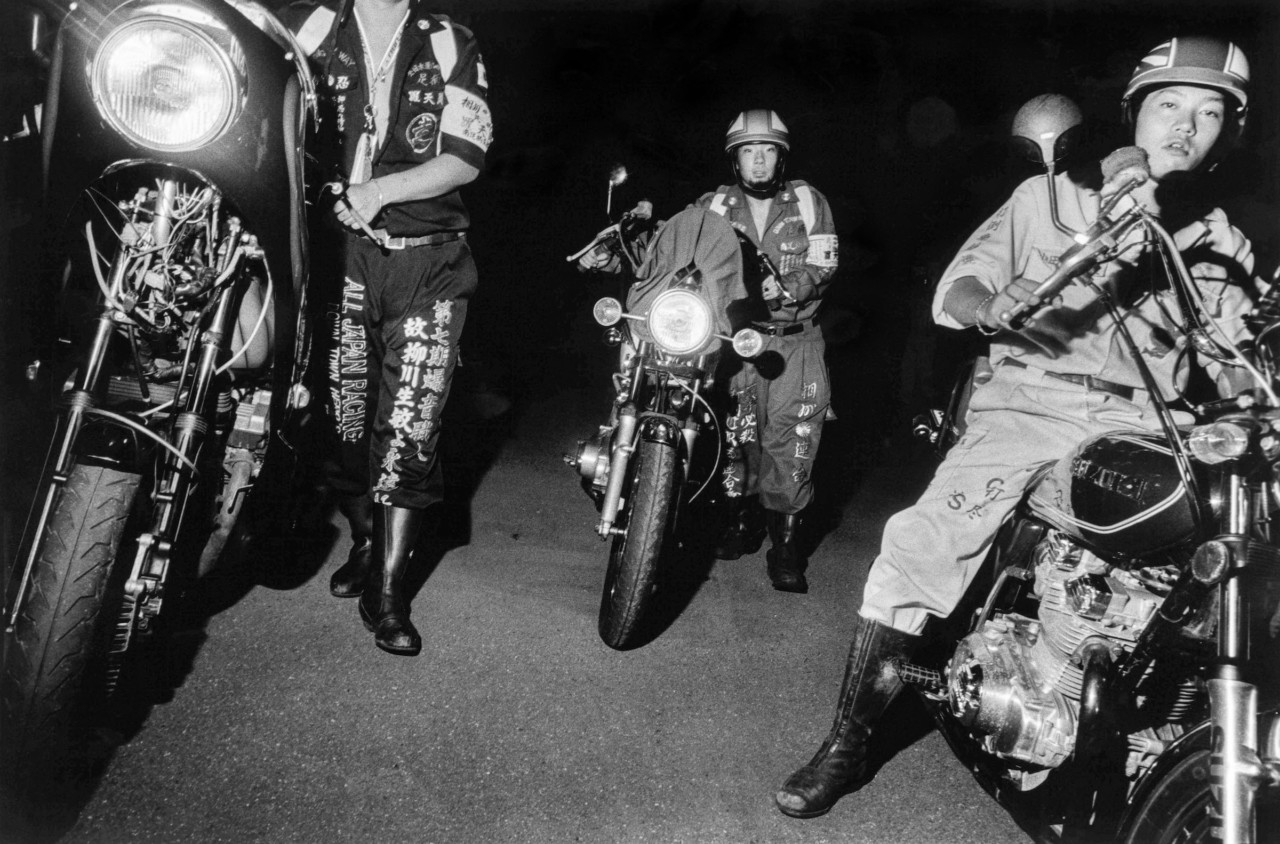

There are some Japanese bikers that you photographed in Go, published in 2000. Was that a very different scene? One assumes you had an interpreter?

Yeah, I did. They are called bōsōzoku…. young kids that will probably go on to become yakuza. The guy in the book with the scarf, with the smoke coming out of his head, he was the go-between. I spent a couple of days with them, and it was very interesting, because I found these young kids that were totally formed at age 17: this one is gonna to be the alcoholic, this one’s gonna be the boss…. You saw it… So, I wanted to continue photographing them until I die or they die, right?

And then one night, I came back to Japan, and I tried to get in touch through this girl who was my interpreter. And she fucked up. What happened was they told her that they were really busy, they won’t have the time to me. She said, “I’m gonna go over your head.” And a woman ain’t gonna tell a yakuza [laughing]!

So that was the end of that! And I felt so bad because I wanted to follow their story.

"My father smoked big cigars. Wore hats. Had pinky rings. You know, the whole nine yards. He was built like a truck. Drove Cadillacs."

-

One aspect of the biker series that seems perfect for you is that it follows this fascination you seem to have with dress codes, particularly communities where there’s a kind of a uniform, but where every individual interprets it their own way – like the yakuza in Go, or the characters at Irish racecourses in After The Off [another Dewi Lewis book, published in 1999]. You said earlier that your way into a series is purely visual, so the potential of the bikers and their heavily customized attire must have must have immediately appealed to you?

There are certain people I’m more attracted to, and there are other people I’m less attracted to. It does have something to do with how they dress, what they wear, you know – not as an unconscious but as a subconscious thing, because obviously clothes are important.

Is there any of your background in that, growing up? You’ve said that your father was a “gangster type.” I probably naively imagine some kind of Scorsese character, a snappy dresser.

In the beginning, my photography was very inspired by my father, who was, well, a caricature – not really, but yes, okay. We’re Jewish. He had thick grey hair. He smoked big cigars. Wore hats. Had pinky rings. You know, the whole nine yards. He was built like a truck: 5’7″ and 240 lb. Drove Cadillacs.

That’s why I have the background to deal with people like this. You have to know how to act. For example, I’ve taken pictures in the [biker] clubs, and I’m going in with a camera a foot away from somebody’s face, and there’s a guy smoking. So you got to feel comfortable enough at three o’clock in the morning to take that picture. And you also have to be prepared to back it up, okay? Because it’s a physical thing, you know?

You grew up street smart, and you are still street smart, you can read these situations. But obviously it’s different photographing within a community, returning to people again and again, to shooting strangers on the street, which is what you are best known for. And obviously, the dynamic is going to change the more you do it. So, is there a point where you’re almost too comfortable?

That’s an interesting question. In sports, you do your thinking before; you don’t do it during. It’s the same thing with photography. Now, when I started the bikers, I would take pictures of most things. The further I go along, there’s very few things I photograph, because I know what situations are good for me. I know where the pictures are going to be.

Most of my pictures here have groups of people, it’s not one person that’s totally zoned in on – it’s about the energy there. It’s about, you know, the vibrancy, the music – I mean, the music is so loud! And in some of the places, people are smoking, and you walk out of there and you’re blinded, your eyes are sore, it’s three in the morning, and I got to drive two hours home! I mean, I’m totally fuckin’ exhausted!

So I think it’s about the dynamic of the situation. This is the first time in my life that I go to places – to keep up my correspondence with them and, you know, because I like them – where I know I’m not going to get good pictures.

But they also appreciate that from me. I’m a part of them. They feed me [laughs]!…. They’re nice guys. From outside, the appearance might look like, “Wow, these people are, you know….” But once you’re in, they’re the sweetest people in the world, the most respectful, the most gentlemanly. They’ll look out for you, you know, they’ll be there for you.

Over the last eight or ten years you’ve been shooting a lot of these now trademark tight-cropped portraits – about the same time you’ve been shooting color I guess. And I saw what you shot in Sinan recently, for a commission, and it’s looser, just like the biker work is looser. Is that how you’ve been shooting all along, really, and the tight-cropped work has just become part of your repertoire?

I wanted to do those kinds of portraits 30 years ago. It took me 25 years to do them because I didn’t have the right camera, I didn’t put myself in the right position. And then I started to do them, and I really figured that I wouldn’t be doing a tonne of longterm candid projects any more [like the bikers].

I’m going to start to do the vertical portraits again, a lot of them. And I’ll continue with the bikers because, you know, I’m still going on, and I have another book planned of pictures of groups. But the thing is, I’m going to continue to do both [approaches] because of the projects that I have in mind in my head.

But I also think it’s quite important to not repeat yourself. I mean, the last five years I was in New York City, I wasn’t into it. And if you’re not into it, you don’t get good pictures. Because my work is about passion. I have to be passionate about it, because I’m a passionate type of person.

Copies of The Circuit are available for pre-order through the Magnum shop. Copies for UK customers are available now.

A contemporary edit of Gilden’s photographs from his 1995 trip to Japan is presented in the limited-edition photobook, Cherry Blossom, published last year (2021) by Thames & Hudson. Signed copies are available in the Magnum shop here.