The Evolving Practice of Olivia Arthur

Olivia Arthur reflects on her evolving practice and speaks future plans in an interview with Alice Zoo from her studio in London.

“Photography is all about discovery,” says Olivia Arthur, sitting at her desk in Hackney, surrounded by photobooks and boxes of negs, prints on the wall. “Even if you’re photographing something at home that’s super familiar, you’re discovering it; seeing it in a new way.” During the pandemic, she photographed ten different things daily — simple, domestic things like the garden, the carpet, the view down the street — pinning little prints to the walls that line the room, watching as time passed through the images she was making.

The photographer — and former Magnum President, and documentary filmmaker, and mother —never ceases to be busy and industrious, even when the world has stopped. She works here at Fishbar, the former gallery space turned studio that she shares with her partner, Phillip Ebeling; and in a borrowed studio space just off Mare Street, in a gorgeous listed building, its insides stripped and empty. It’s the perfect venue for editing work, with wide bare walls on which she tapes laser printouts of images, playing with orders and layouts. Arthur lives in a flat above the Fishbar studio space with Ebeling and their daughters, and so having this other place to come to, away from home, is a boon.

Over the last few years her practice has entered a new phase. Arthur’s early projects were characterized by concern with the fates of women — in Jeddah Diary, for example, and The Middle Distance — and so it’s fitting that this recent shift seems to have been initiated by a very personal, very intense experience of womanhood: her first pregnancy.

“Your body is no longer yours,” she recalls. “It sort of becomes public. You’re having this baby, you’re growing this human, and you’re doing something that is more than just being yourself.” She was awed by the body’s seemingly automatic knowledge, its ability to grow a being without conscious intent or direction. “It’s an incredible thing, the way your body takes over.”

Her daughter was born at the beginning of 2015. Around that time — and then, over the markedly intense period of a few years that included the pandemic and her Magnum presidency — her interests began to shift. First, in India from 2016 to 2018, she made a work alongside Bharat Sikka called In Private, an exploration of gender and sexuality in Mumbai; a controversial subject, given that homosexuality was criminalised in India until 2018. Her subjects, in that work, look courageously towards the camera, clothed or naked, offering themselves and their bodies to the lens with the resolved and delicate strength of the persecuted.

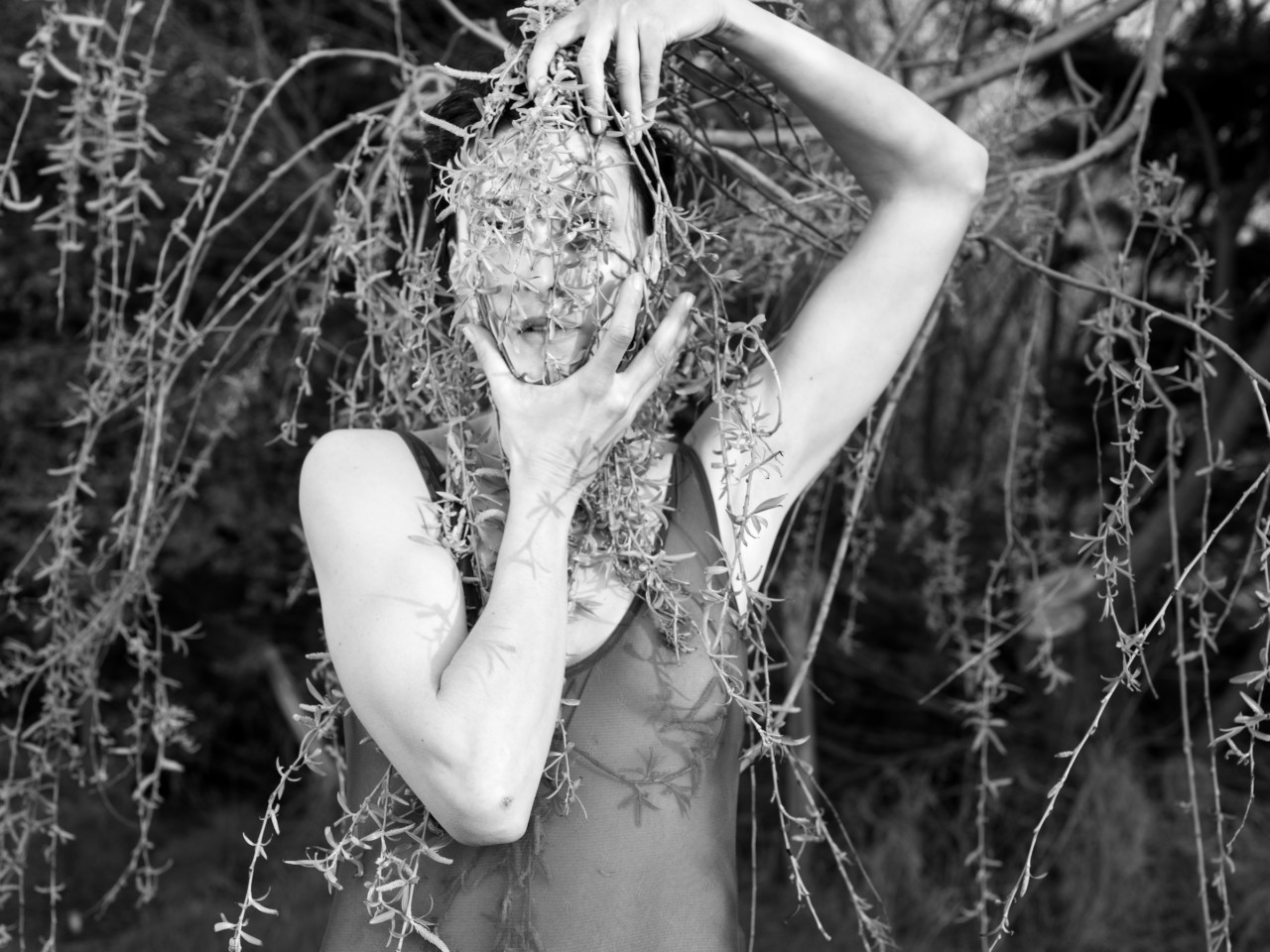

Over the pandemic, Arthur worked on commissions in Europe which furthered her investigations around touch, intimacy, and gesture: she spent time with an amputee ballerina, an acupuncturist, a professional cuddler. She had a second daughter, and made work about that experience, too, turning the lens on herself and her family in Waiting for Lorelei. Eventually, all of this research around the physical led to an interest in the fusing of contemporary technology with the body. She met Alex Lewis, for example, a man who lost all his limbs, and part of his face, after an illness; and Rob Spence, a filmmaker — and member of a network of cyborgs — who’d installed a video camera in his prosthetic eye.

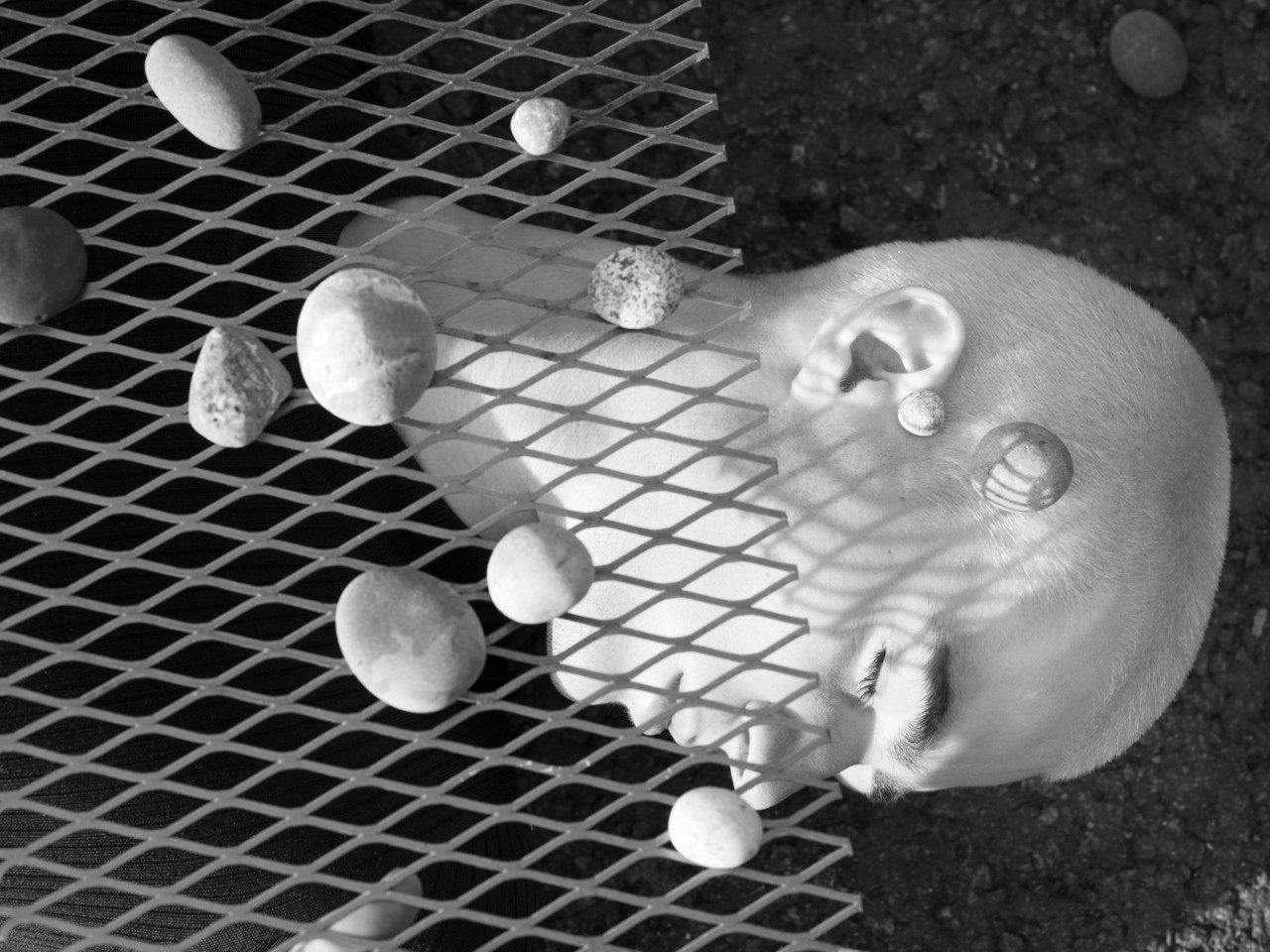

The images currently being sequenced on Arthur’s studio wall will bring these works together as a book. Combined, they form a documentary project based not around place or an individual narrative, but instead around ideas of the body itself, with a working title of My Body as a Machine. An image of her own pregnancy begins the book; it was the first time Arthur had turned the camera on herself, the photograph a reflection of the feeling that her body had suddenly become public, touched and advised without solicitation or consent. Her response to that transformation grounds the work. “The way we feel about our bodies and what they can do and be were suddenly ideas, questions I couldn’t let go of,” she writes in a text alongside that first picture.

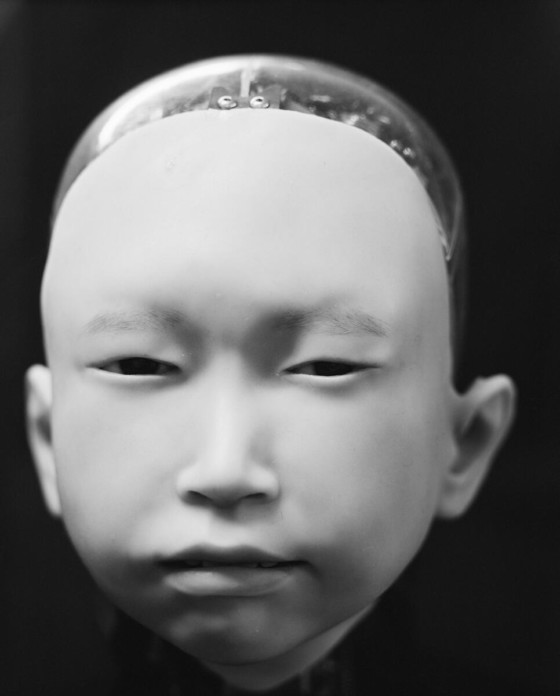

She photographed a child robot creasing his face in faux-dismay, made Muybridge-inspired “motion studies of enhanced human motion” — amputees walking, running, dancing. She photographed her daughter standing unassisted for the first time. “I saw some amazing things, and photographed some amazing things,” Arthur tells me, of the last several years spent making work around these subjects, “but I came out of it in awe of the body, like: the ultimate machine.” Arthur’s portraits of robots are strong and uncannily sympathetic, but alongside the vivid and imperfect texture of human flesh documented minutely elsewhere in the work, their smoothness reads as strange, lacking something essential — humanity, perhaps. The last image in the book is a grid of the grainy, indistinct images made by Spence’s camera-eye: Arthur herself, a dark shape alongside her camera on its tripod. “It begins and ends,” she says of the work, “with me.”

Arthur’s interest in physicality and embodiment is borne out not only in her subject matter, but also in her working practice. There’s the large format: she has been working with 4×5 Linhof and Graflex cameras, as well as a 10×12 wooden camera, since 2015, all of which are slow, hefty, and require a considerable amount of maneuvering (the tripod, the sheet film, the precarious focus, the head under the dark cloth) to even make a frame to begin with. At a recent show in China on the subject of touch and technology, her images were displayed above a row of small sculptures made by friends and family members asked to grip a piece of clay so that the impression of their hand would be left; holding the sculpture might, in turn, feel like holding the hand of someone absent. And then there’s her repeated use of collage and layering, a method first adopted in 2014 with Stranger, and which she has now returned to. “It’s not really a fine art practice, but it’s a little bit more in that direction, it’s more…” Arthur trails off for a moment, thinking. “I’m playing more, right?”

On commission alongside a group of Magnum photographers in Mexico, Arthur found her way to Otay, a Californian mountain whose south face is the territory of the Mexico-US border. In the work of the same name conceived during that trip, original photographs by Arthur, taken on and around the mountain, are layered over and brought together with an archive of images taken by a local photographer, and pressed flowers and leaves — she had the impulse, she says, to “put the pictures back in the mountain”.

Another project began unexpectedly and tragically, when she began to make a children’s book after the suicide of a close friend in 2014. The book, Lee and the Sea Things, was for the friend’s daughter, who was just a small child when she lost her mother. It tells the story of a young girl, Lee, wondering where her mother disappeared to, and the fable-like narrative that is recounted to her of her mother’s spiriting away by creatures that live in the sea. Accompanying original text written by Arthur are a series of collages, cut and colored largely from her own photographs. The illustrations are profound and eerie, strange and sad, matching the elegiac, contemplative tone of the text. At the book’s end, Lee swims with the titular Sea Things herself, but instead of spiriting her away, too, they are benevolent, taking her on a tour of the coast and its bays. “…she started to wonder why it was that some plants can survive underwater when others need the air to grow,” the book ends.

“I always wanted to make something for her that just explained my point of view of what happened,” says Arthur, remembering the impulse that began the book. “And it took me many more years than I thought it would.” At first, the project was entirely personal: a wish to soothe, or to explain the inexplicable, to create a narrative as ballast against tragedy. “This has always been something that wasn’t part of my “work” — it was just something that I wanted to do,” Arthur reflects. “But then, at some point, I realized that it kind of was, and it is… We don’t have to be so strict about what’s part of our work.”

This embodied way of making images — cutting, sticking, rearranging, using hands to shape forms on paper or in clay, rather than adjusting pixels and contrast on a screen — has roots in Arthur’s earliest practice, too, when gesture necessarily shaped her earliest portraits. In her first works, traveling through the Middle East, she didn’t share a language with her subjects, working with fixers and translators. Often the nuances of the photographic scenario would be communicated wordlessly anyway, through gesture — through the body.

“When you photograph people, and you don’t speak the same language, body language is really important — they read you in a different way. It’s not just about saying nice things to them,” Arthur recalls. “It’s somehow, in a funny way, more personal.” It’s almost as though, with spoken language removed, Arthur was able to interact differently, using a more instinctive, intuitive language of gestures. It was only when a friend pointed it out to her that she realized that the very stance that her Hasselblad necessitated — held at the belly, the photographer looking down into it — was a posture of humility, of deference: a bow.

Years on from these works, Arthur remains committed to this personal, authentic approach to portraiture, as with her work on large format (the disappearance under the dark cloth perhaps another kind of humbling). “Obviously what you get with these large formats looks amazing,” she says, “but it’s also about process for me: the way of using the camera, the way of taking one shot at a time, and then having to reload, and so you really engage with the people that you’re photographing in a different way, because you make one shot at a time, and you think about it, and they know what you’re doing.”

“I think it’s a very honest way to take pictures,” she continues. “I suppose because it’s so slow and cumbersome, it’s very clear what’s happening. There are no surprises, right? Particularly in terms of portraiture: I feel that people know what kind of image you’re making of them, and it’s a slow process — you work it out together.” This belief in process as a means of working things out has begun to seem characteristic. Arthur hadn’t intended, when she became pregnant in 2014, to begin a long cycle of projects around the body; but she let one thing lead to another, following her interests as they presented themselves.

In one sense, it’s difficult to write a satisfyingly tidy narrative of Olivia Arthur, a photographer with such a varied output: alongside these multiple projects and mediums, she has recently photographed fashion stories for Crash Magazine, in collaboration with designers including Dior and Saint Laurent; made a new film — fictional — about a prisoner walking the Camino de Santiago, The Stop Game; another film project, TiChan, in collaboration with Ebeling, documenting a transgender woman named Charlotte as she moves through her transition; and then of course there’s Fishbar, which used to be an imprint as well as a gallery space, also shared with Ebeling, and with whom she is now beginning to devise a series of residencies.

In another sense, though, all these works are completely coherent, despite their ostensible variety, in their springing from the same ideological well. Arthur, known for her unfixed style, her willingness to adopt new methods and aesthetics depending on the project, grew up as a diplomat’s daughter, living in multiple different places as a child, moving from country to country; she learned to see home as a feeling created amongst family, rather than a place. Her voice, then — her identity as an artist — springs not from an aesthetic but from a sensibility: one of reinvention, continual trials and renewal, a willingness to experiment.

As we meet her now, moving images around on her studio wall in Hackney, it strikes me that perhaps Arthur’s native language is that of instinct, that sense that’s linked so closely to the body and its urges, the unconscious processes it carries out whether we will it or not. “I think I’m in the process, right now, of seeing all those things that I’ve done, and understanding how they all come together,” she says. “I’m enjoying it — understanding myself by looking back at the work I’ve made in these years.”

Olivia Arthur‘s work is currently exhibited as part of Close Enough: 12 Women Photographers of Magnum, on view at the Hangar in Brussels until December 16.