The Joy of Seeing: Magnum Street Photography

Pauline Vermare reflects upon the breadth and evolution of street photography, as well as the collective's deep history within it, as Magnum photographers launch their first online course.

The Art of Street Photography, an online course in which seven Magnum photographers share their advice, is now available on the Magnum Learn platform. It is one of the seven online courses featured in our Summer Sale, which runs from August 1 to midnight (EST) on August 31, 2023. For 20% off the course, use the code SUMMER20 at checkout.

“I prowled the streets all day, feeling very strung-up and ready to pounce, determined to ‘trap’ life— to preserve life in the act of living.”

—Henri Cartier-Bresson

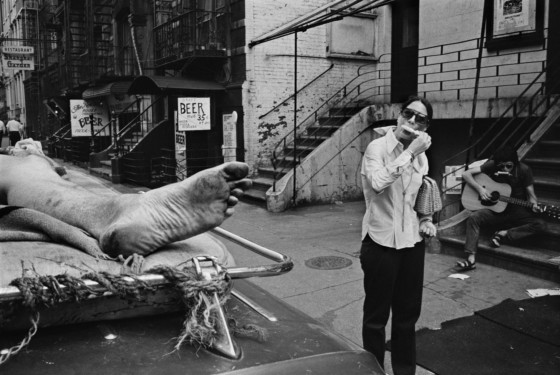

There is not one definition of “street photography”: the word ‘street’ is a euphemism, standing essentially in opposition to the studio that preceded it, and ultimately to any kind of restrictive frame – it is a photography that is free of rules. Street photography is about finding beauty in the mundane, in everyday life, away from the factual appeal of journalism or the instantaneous beauty of Pictorialism. As Carolyn Drake suggests: “Every photographer should define what ‘the street’ means to them”. There are of course a few defining elements for the genre. First, a strong locus: the sense of a place. Legendarily, the streets of New York –Manhattan, Brooklyn, Harlem, Coney Island -filled with ubiquitous fictions; and those of Paris, London, Tokyo, Havana, Valparaiso… But “street” is really a code name for any public space, a strange or familiar scene available to all, allowing photographers to shoot complete strangers. In this regard, subways and trains were always a photographer’s favorite– from Walker Evans’s subway portraits (1938-41) to Bruce Davidson’s own color Subway series in the 1980s, capturing the ever-inspiring gaze of passengers in transit.

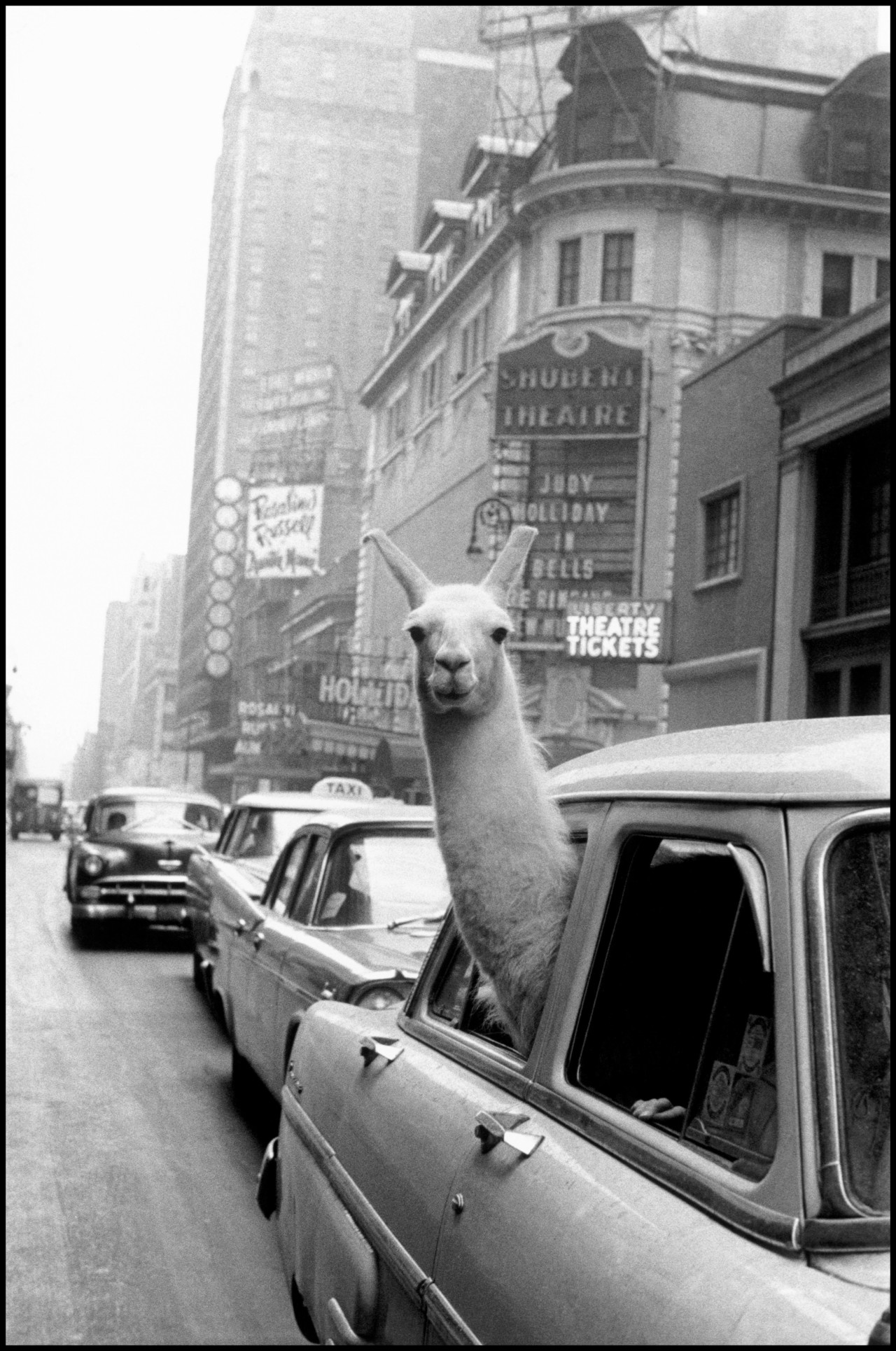

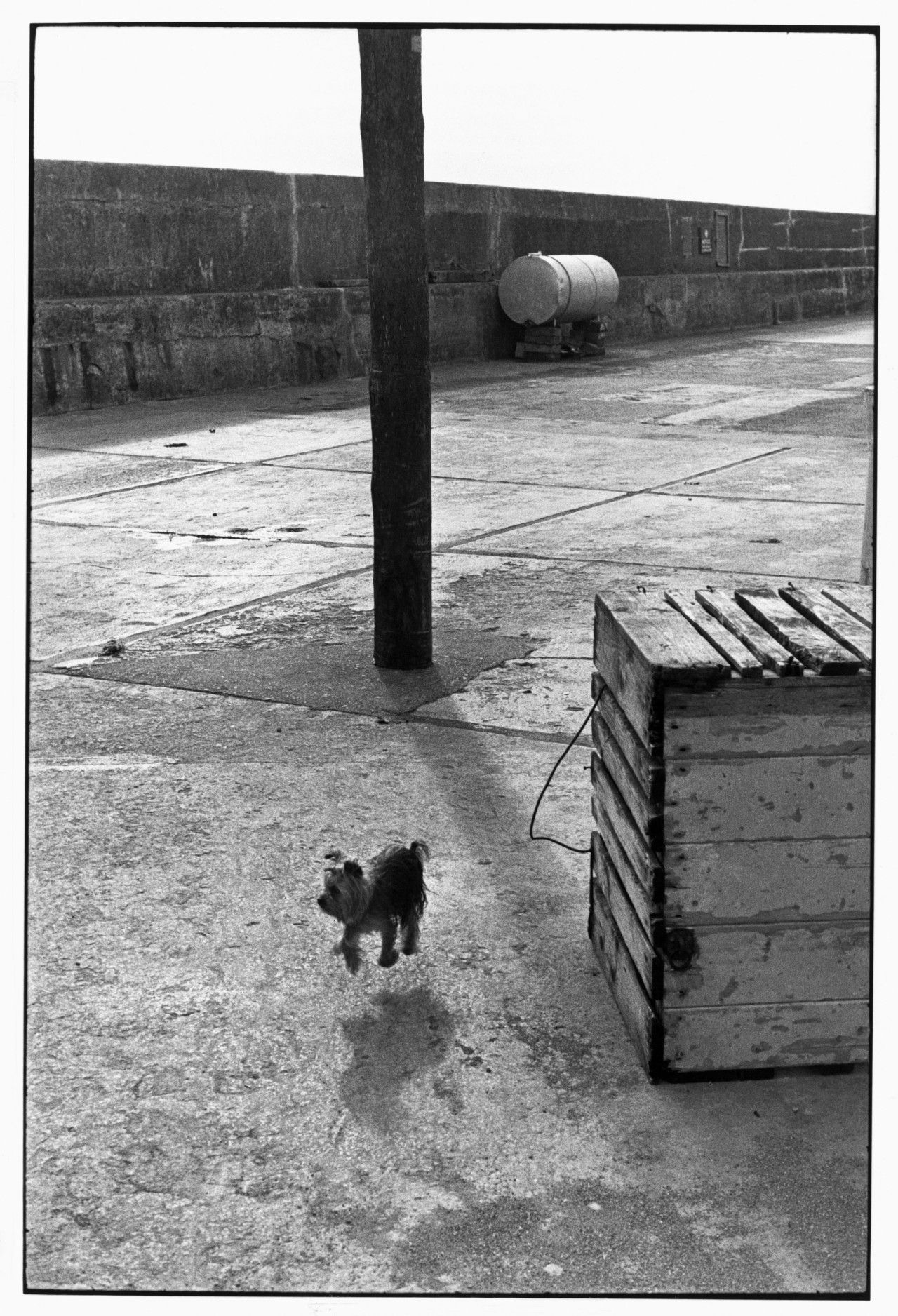

The second defining element is a human presence: bodies, faces, silhouettes, that almost always belong to strangers (the exception being the photographer’s own shadow or reflection in street self-portraits). If Magnum photographers tend to focus on human nature and the human condition, some, like Ernst Haas, found street beauty in graphic elements alone: a torn poster, iron work in the pavement. Animals also make for very rich and lively subjects: while Elliott Erwitt is the most famous of the “street animal photographers”, Richard Kalvar’s nonchalant dog became one of his best-known images, and Inge Morath’s “Llama in Times Square” is one of the most popular photographs in Magnum’s archives.

The third and final defining element, perhaps the most crucial, is the idea of ‘chance’, and how to use it: to anticipate the unexpected. Street photography requires the utmost level of curiosity and openness to the world –a strong belief in serendipity.

"The third and final defining element, perhaps the most crucial, is the idea of ‘chance’ and how to use it"

- Pauline Vermare

Street photography is the art of gleaning what is at hand – subjects, lights, shapes – to create beautifully composed and arresting images. It is an artistic form of hunting and gathering, a scavenger hunt led by a conscious or subconscious urge to collect patterns and scenes that offer themselves freely to the mind and eyes of the photographer. In the street, the photographer becomes the hunter, seeking exciting subjects and compositions. Obvious comparisons can be drawn between the act of photographing – especially with a small ‘point-and-shoot’ camera – and the actual act of shooting, with a gun. Photo historian Clément Chéroux developed the analogy in depth in regards to Cartier-Bresson’s approach in Le Tir photographique, bringing it back to Cartier-Bresson’s hunting with his family as a young man. Street photography is motivated by the ecstasy of the act of shooting itself. As Cartier-Bresson put it, paraphrasing Molly’s monologue in James Joyce’s Ulysses: “I enjoy shooting a picture. Being present. It’s a way of saying, “Yes! Yes! Yes! It’s an affirmation.” Another analogy lies within Japanese archery, in the focus, the tension, and the release. Henri Cartier-Bresson would often refer to an essay called Zen in the Art of Archery by German philosopher Eugen Herrigel (1948). For some, like Cartier-Bresson or Sergio Larraín, street photography provides the highest form of awareness, and a complete presence in the world.

"In the street, the photographer becomes the hunter, seeking exciting subjects and compositions"

- Pauline Vermare

The genre was born alongside photography itself, in the mid-19thcentury, and gained its popularity in the early 1930s with the advance of smaller, portable cameras. Photography quickly became the weapon of choice for social change, and for art. The Photo League was founded in New York in 1934 with the aim of “integrating formal elements of design and visual aesthetics with the powerful and sympathetic evidence of the human condition.” At that very same time, a group of young photographers – Cartier-Bresson, Robert Capa, George Rodger and Chim (David Seymour) – was taking to the streets of Paris to act towards a fairer society. They later founded Magnum Photos, in 1947. All of them shared an acute sense of social justice, a sympathy for the workers’ plight, the struggle of the poor, and an innate sense of aesthetics. While they actively worked for the leftist publications of the time, such as Regards, they also produced beautiful, spontaneous street photographs in France, and later in Spain while covering the Civil War. The misfits and the dispossessed were central figures in their work.

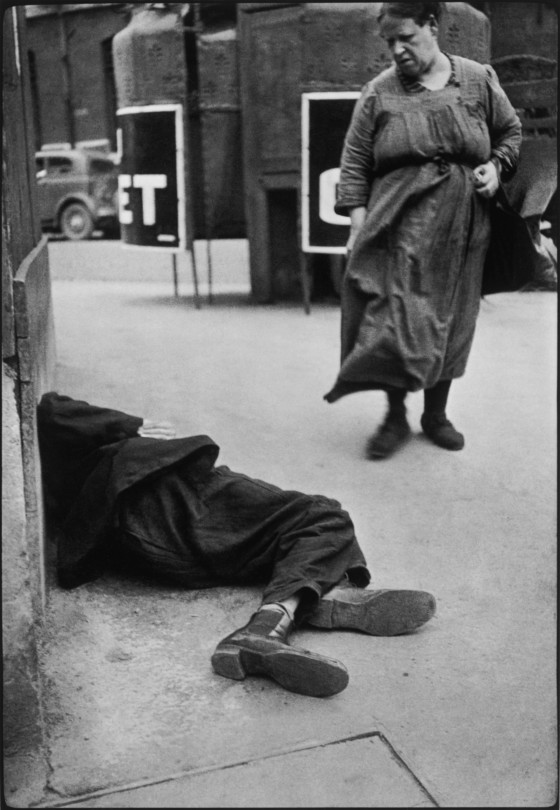

In one of Cartier-Bresson’s first photographs, taken in the early 1930s in La Villette, a working-class woman is looking down (with pity, or anger, or a completely detached gaze?) at a homeless man lying on the ground, whose face we cannot see. Beyond the perfect composition lies the photographer’s intuitions and astute social awareness. In one of Capa’s photographs, a homeless man is sitting in a park, face down, curled in on himself. One can feel the photographer’s concern, and perhaps some sense of self-identification. Both of these images, combining social critique and poetry, bring to mind the Blind Woman that Paul Strand, a co-founder of the Photo League, photographed in 1916 in the streets of New York.

"One can feel the photographer’s concern, and perhaps some sense of self-identification. Both of these images, combining social critique and poetry, bring to mind the Blind Woman that Paul Strand, a co-founder of the Photo League, photographed in 1916 in the streets of New York. "

- Pauline Vermare

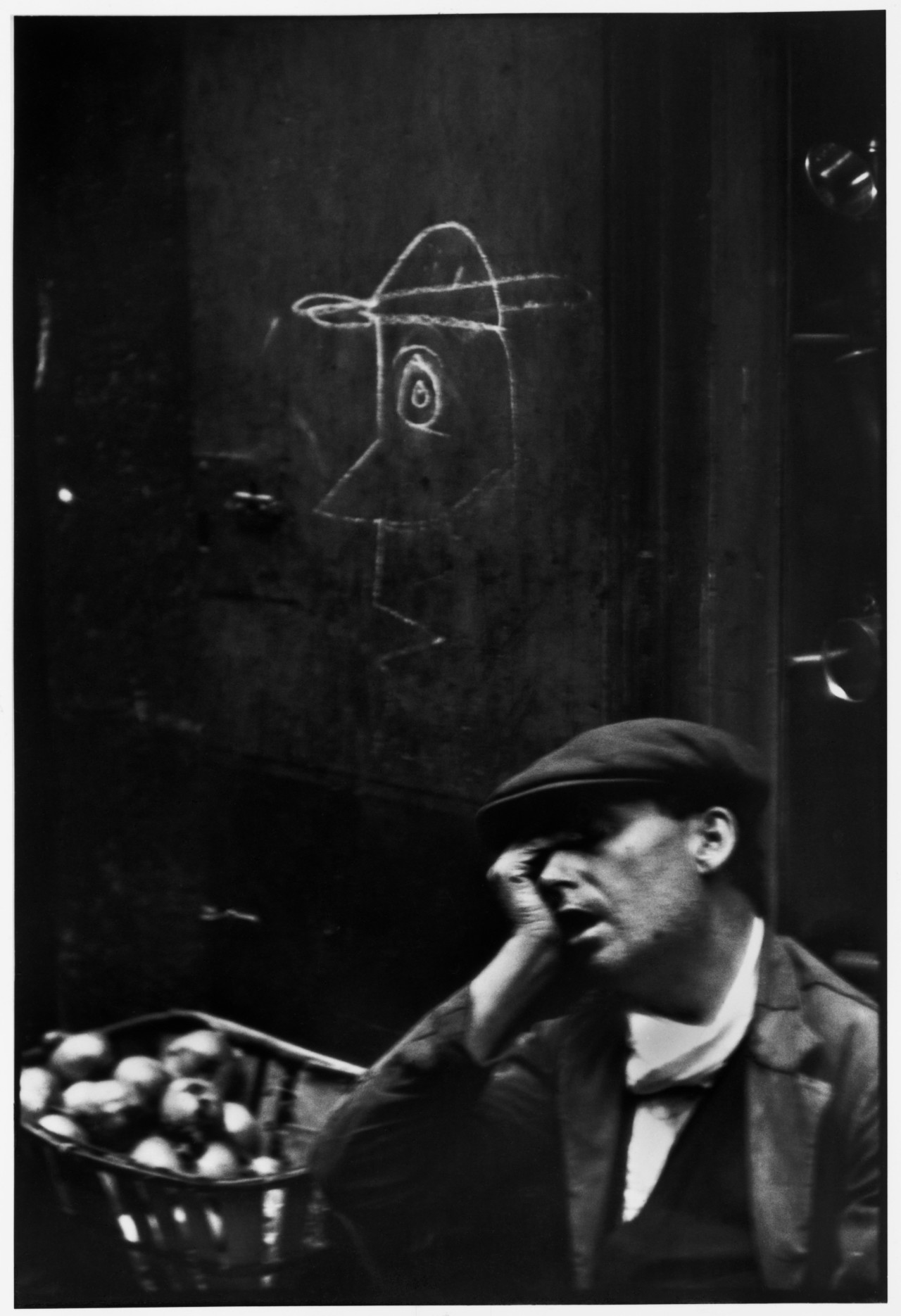

The roots of modern street photography can be found in Surrealism. In his seminal book The Early Work (1987), MoMA Chief Curator Peter Galassi described Cartier-Bresson as “a young vagabond, possessed by Surrealist ideals of absolute personal and artistic freedom.” He added: “Alone, the Surrealist wanders the streets without destination but with a premeditated alertness for the unexpected detail that will release a marvelous and compelling reality just beneath the banal surface of ordinary experience.“ In the introduction to The Decisive Moment (1952), Cartier-Bresson explained: “I craved to seize the whole essence, in the confines of a single photograph, of some situation that was in the process of unrolling itself before my eyes.” As he later put it – “Voir est un tout”. Poetry would arise from symbols and correspondences, making for the most beautiful visual epiphanies: “I saw a fruit vendor sleeping against a wall and was struck by the surprisingly gentle and articulate drawing scrawled there.” (about Barrio Chino, 1933). It seems fair to say that Cartier-Bresson invented modern street photography – and, in doing so, established it as a highly personal and intuitive form of art.

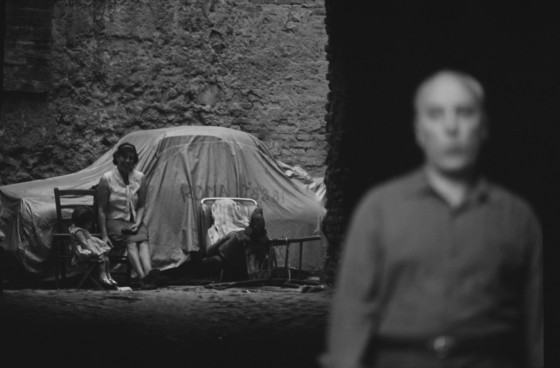

Many Magnum photographers followed suit. In the late 1940s and 1950s, Erwitt arguably produced his most important work in the streets of Europe and America. So did Morath, who made some of her greatest images on the road and in the streets of Europe, the Middle East and the United States during the 1950s and 1960s. In that same exploratory vein, prevalent at the time, Bruno Barbey composed one of his most acclaimed series, The Italians, “to try and capture the spirit of the place, without thinking in terms of history.” At that time, street photography was seen as the best way to explore the world – more often than not a foreign world. One of the turning points in the history of modern photography, Robert Frank’s The Americans, first published in 1958 by Delpire, was a revolution in the genre.

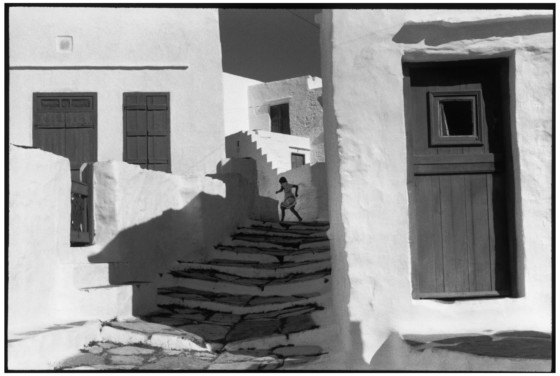

Frank, who nearly joined Magnum in the early 1950s, was exploring a country that was utterly foreign to him. His ambiguous, subjective, and diaristic voice was deeply rooted in existentialism. Frank radically redefined what photography was, and what it could do. It was during those years that Larraín produced, with equal profoundness and freedom, the most graceful and poetic work in the streets of London, Paris and Valparaiso. Larraín explained: “A good image is created by a state of grace. Grace expresses itself when it has been freed from conventions, free like a child in his early discovery of reality. The game is then to organize the rectangle”. Brought to the world’s attention by Agnès Sire, the head of the Cartier-Bresson Foundation, Larraín’s work, particularly his series on Valparaiso’s vagabond children, is arguably one of the most important bodies of work in the history of street photography.

Another revelation of the late 1950s, early 1960s were Haas’ early experimentations with color in the streets of New York. Haas, undoubtedly the most modern Magnum photographer at the time, explained: “Bored with obvious reality, I find my fascination in transforming it into a subjective point of view. Without touching my subject I want to come to the moment when, through pure concentration of seeing, the composed picture becomes more made than taken. Without a descriptive caption to justify its existence, it will speak for itself–less descriptive, more creative; less informative, more suggestive; less prose, more poetry.” Haas started to work in color around the same time as New York street photographers Helen Levitt and Saul Leiter. Like Cartier-Bresson and Leiter, he was a painter before he became a photographer. His painterly images were exhibited at MoMA in 1962. Curator John Szarkowski wrote: “No photographer has worked more successfully to express the sheer physical joy of seeing.” Harry Gruyaert is a direct descendant of this extraordinary line of street colorists.

"Undoubtedly the most "street" of all contemporary Magnum photographers is Bruce Gilden, the gritty New Yorker whose frontal street portraits have become emblematic of modern street photography"

- Pauline Vermare

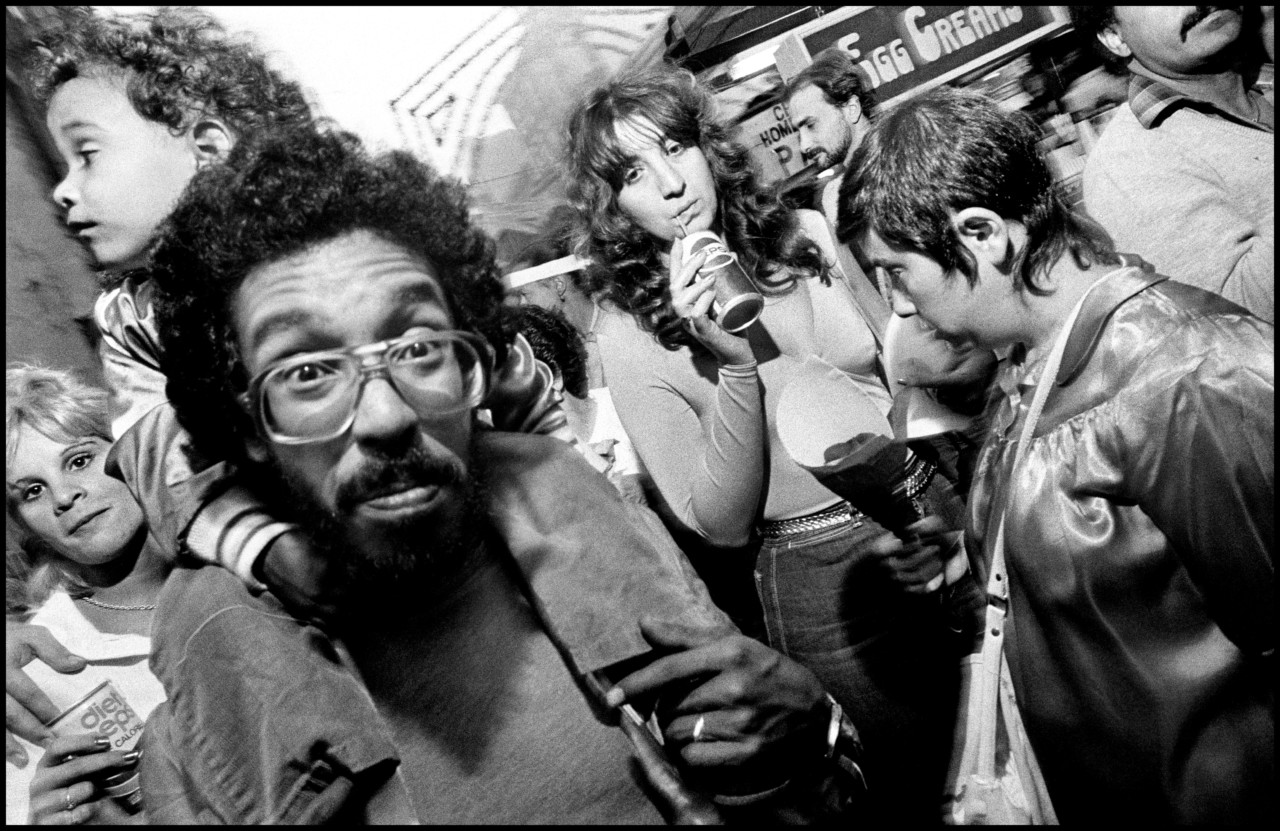

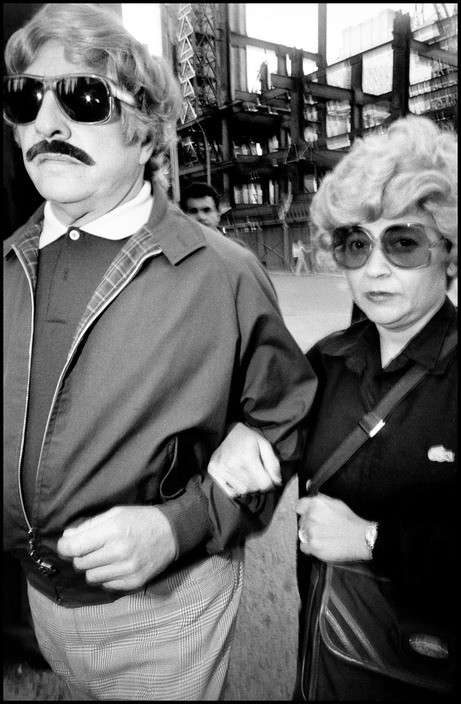

Street photography established itself as a proper style in the 1970s and 1980s with legendary figures like Garry Winogrand in the U.S. or Daido Moriyama in Japan, who revolutionized the genre by giving it an edge – the street as a music stage (these seeds had been planted two decades earlier by William Klein). In this vein, undoubtedly the most “street” of all contemporary Magnum photographers is Bruce Gilden, the gritty New Yorker whose frontal street portraits have become emblematic of modern street photography. Blunt and raw, his portraits–often flash-lit and impossibly close to his subjects, are immediately recognizable. He (somewhat surprisingly) explains: “I became a photographer because I’m basically a shy person, and on the street I didn’t have to talk to anybody.” He did in fact befriend a few of the people that he photographed, and it is fair to say that he felt a kinship with some of the improbable characters he instinctively spotted on the street.

While some photographers like to proceed with an invisibility cloak (famously, Cartier-Bresson); others deliberately choose to be visible, if not extremely visible, like Gilden; or loud, like Erwitt, who famously used a horn to get dogs to jump in his pictures.

The flash has been one of the greatest stylistic and philosophical questions throughout the history of photography. While Cartier-Bresson categorically refused to use it (too aggressive, not natural), it became others’ trademark: Gilden, or Martin Parr, who is mostly known for his vibrant color work and social satire, but also made some of the most striking street photographs in black and white in the 1970s and 1980s; and the younger Magnum generation, like Sohrab Hura or Drake, who explains: “In the Wild Pigeon work, I used very little flash. In Vallejo I’m using a lot of it. That decision was partly rooted in a desire to change my method after spending years working in the same way, but also rooted in wanting to avoid making secret pictures. Now I’m almost always confronting and interacting with people I photograph, and the flash adds to that sense of direct exchange and also hopefully gives a feeling of creating something from the real world as opposed to documenting the real world.”Making art from reality, or what Cartier-Bresson called “L’imaginaire d’après nature”.

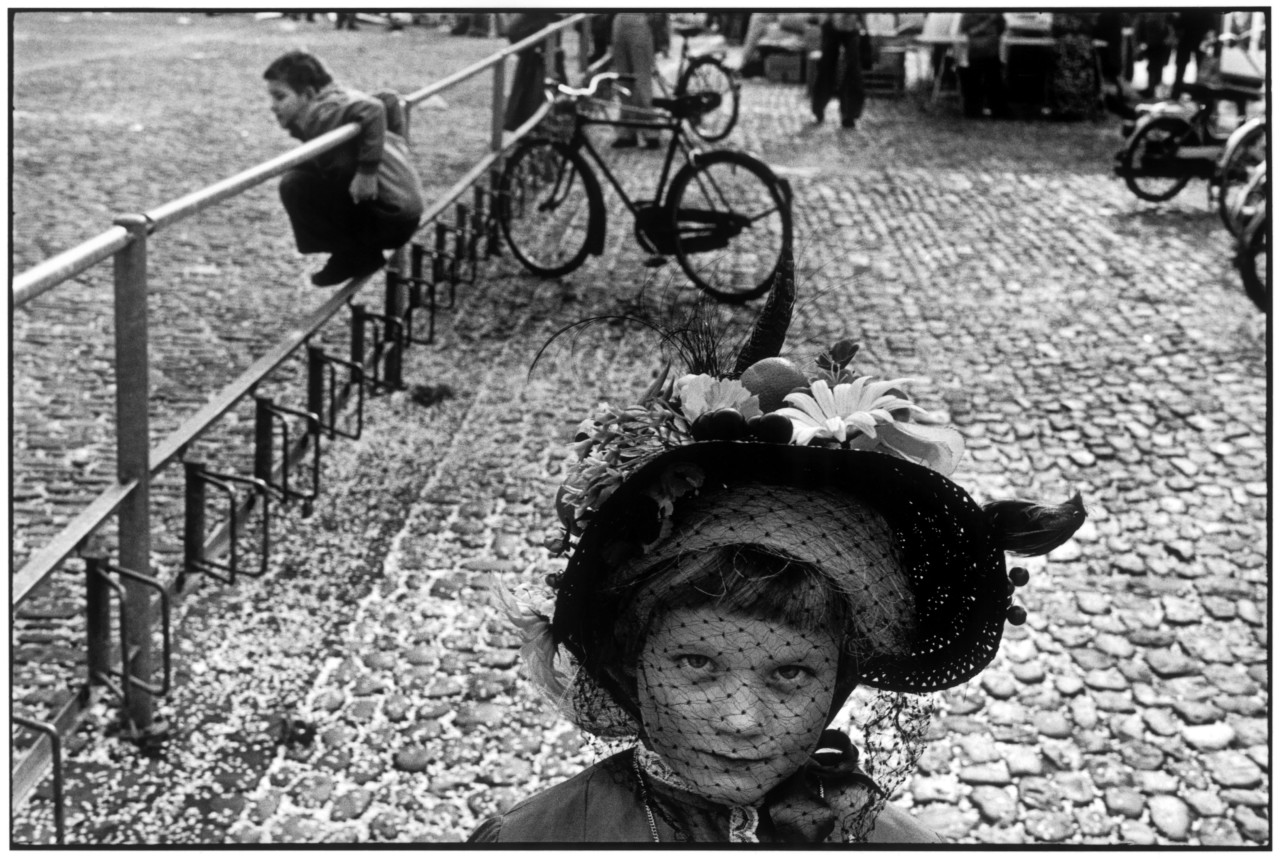

Perhaps one of the main appeals of street photography, for both the photographers and the viewers, is to secretly enter the lives of complete strangers. Some might say that the subject’s lack of awareness is key, but in certain instances the direct gaze of the stranger into the lens is what makes the picture. In Gilden’s work particularly, this is what creates the tension–a confrontation of sorts, the reaction that the photographer seeks. In a very different way, Martine Franck, who was also shy (Cartier-Bresson, her husband, would joke that she was “not made to walk the streets”), made some of the most striking street portraits, particularly of children, who were visibly aware of her presence, sometimes staring at her. Some photographers explain that they love shooting on the street because it gives them a chance to engage with strangers. One of the most iconic figures in the history of photography, Diane Arbus was known for creating a relationship, sometimes intimate, with the characters she found on the streets.

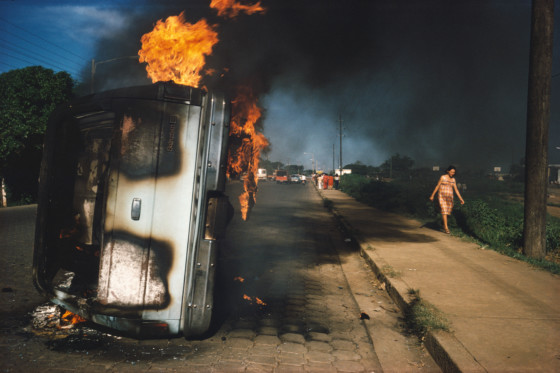

Because the camera can play the role of a sketchbook, or a journal, recording the interstitial moments of everyday life, and because Magnum photographers are such avid travelers, it is fair to say that many Magnum photographers, if not all, have done some street photography at some point in their life. Street photography is considered to be an apolitical form of straight photography, but the genres of photography are porous. Hence, some Magnum photographers who might not be considered “street photographers” happen to have made street photographs of the highest order. For instance, Gilles Peress, in Iran or Northern Ireland in the 1970s and 1980s; or Susan Meiselas, in Nicaragua. Meiselas explains: “I am not a street photographer–but I did shoot the streets in Nicaragua, and I didn’t know these people. It is not street photography in the traditional sense, but I suppose it can be considered such.”

Both Peress and Meiselas were included in the pivotal survey Bystander: A History of Street Photography (1994) that established both the concept of “street photography” and the expression itself. Some of the younger generation of Magnum photographers that became well known for documenting political violence, including Christopher Anderson, Moises Saman or Peter Van Agtmael, have also been turning to more intimate and artistic subjects, in the past few years, including street photography. Anderson recently produced a stunning series of street portraits in Shenzhen that set themselves apart by their modernity and their fiction-like nature. The labels – “war photographer,” “documentary photographer,” “photojournalist,” or “street photographer,” are quite arbitrary, and the initial intention of the photographer sometimes differs greatly from how his work is perceived. Josef Koudelka said of his legendary photographs of the Soviet invasion of Prague, in 1968, : “I picked up the camera, went out on the street, and I photographed just for myself. I’d never photographed events before. These pictures weren’t meant to be published.” What he had seen as street photography became one of the greatest reportages ever published. Koudelka, who was in his own terms driven by “a rage to see”, went on to leave his native Czechoslovakia and live in a state of nomadic exile in Europe and the U. S. that led him to produce some of the most extraordinary street work of the past 50 years.

"The genres of photography are porous. Hence, some Magnum photographers who might not be considered “street photographers” happen to have made street photographs of the highest order"

- Pauline Vermare

"Time and patience are essential in street photography. One has to walk a lot, and, sometimes, one has to wait for thephotograph to happen; in other cases, the photographer will wait until a subject enters a chosen stage –the foreseen composition"

- Pauline Vermare

Time and patience are essential in street photography. One has to walk a lot, and, sometimes, one has to wait for the photograph to happen. In some cases, the photographer will wait until a subject enters a chosen stage–the foreseen composition. This is what Cartier-Bresson did to achieve his famed photograph of a little girl running down the stairs in Sifnos; or Raymond Depardon did to make one of the most delicate New York street portraits: “I had been waiting for several minutes. She placed herself in the frame, on her own. Freely”. Or take the impossibly well composed São Paolo rooftop scene by René Burri, which writer Teju Cole described in The New York Times Magazine as “one of the handful of pictures that truly convey the oneiric possibilities of street photography”. It is not a case of staging, but a case of recognizing that, in some instances, the form is what makes the photograph. Magnum photographers’ styles vary greatly, from the frenzied dance of Cartier-Bresson to the marathon of Gilden–to the slower pace of Depardon, Gruyaert, Mark Power or Drake. The moods range from poetic to raw; from psycho-thriller to comedy; from social satire to film noir; from roman photo to mystery… If most use small format cameras, others prefer to use medium or large format cameras to shoot the streets. The larger formats, and the tripod, allow the photographer to take more time to compose painterly photographs. In fact, in the case of Power, who works more like a painter with a canvas, it would be more accurate to talk about a ‘photographer of the streets’ rather than a street photographer.

"If most use small format cameras, others prefer to use medium or large format cameras to shoot the streets. The larger formats, and the tripod, allow the photographer to take more time to compose painterly photographs"

- Pauline Vermare

One concept that seems consistently attached to “street photography” is that of a “decisive moment.” Agnès Sire, director of the Henri Cartier-Bresson Foundation, thoughtfully deconstructed this myth in the facsimile of The Decisive Moment, published in 2014 by Steidl. The quote, commonly but wrongly attributed to Cartier-Bresson, was in fact borrowed from the Cardinal de Retz and used as an excerpt for Images à la Sauvette, the original, French version of The Decisive Moment (1952). It soon became a catch-all label which Cartier-Bresson later in his life saw as a limiting and irritating burden. In her essay, Agnès Sire explains that the style and philosophy of Cartier-Bresson were far too complex to be reduced to this one phrase, and, most importantly, that there is far more in photography than “decisive moments.”

If the appealing concept of a “decisive moment” – the moment when form and content align – is of essence in street photography, the idea of the “unassuming moment”– what Depardon coined “le moment faible” – is just as important: the low intensity moments, the in-betweens. Depardon, Power and Drake, working at a slower pace, all succeeded in creating beautiful photographs of “unassuming moments”. A few of the younger Magnum photographers have been working on redefining the genre–its form and its content, while steering the narrative away from stereotypes. As Drake explains: “The problems I had with traditional street photography that I’m trying to work through–especially in America, I think the fact that this kind of photography rests in the hands of white men is because those are the people who have traditionally felt most safe on the streets, and felt like it is their turf.”

Digital cameras, omnipresent phone cameras, the fast and global dissemination of images on the internet, and a more regulated public space, have contributed to revolutionize street photography over the past 20 years. While the progress of technology certainly encourages the act itself by suppressing any form of technological limitation, the sheer volume of images that results makes the editing process harder than it already was. What is more, shooting in public space has become more difficult, controlled, and there is a new type of fear when photographing strangers. Today’s streets are not the streets of Vivian Maier. Photographers need to find ways to circumvent or subvert the rules with new styles, new approaches. Perhaps more so than any other form of art, though not dissimilar from cinema or literature, street photography allows for an exploration of the space between reality and fiction: it is the art of the unknown, allowing imagination to run wild–that of the photographer, and that of the viewer. As with all art forms, street photography nourishes itself from the reality and the mythologies of its time. For this very reason, one must hope that it will always be renewed and reinvented. The past and present generations of Magnum photographers show us that there are many ways to do so.