The Shape of a Circle

Rounded forms provide a multitudinous source of visual fascination: exploring them, from the microcosmic to the macrocosmic, reveals much about human nature

As part of Magnum Photos’ recent Emerging Writers in Residence program, six early-career photography writers were invited to research and respond to a topic of their choosing in Magnum’s photographic archive. This text is one of the works that were produced on the residency — see all six at the link here.

Noor-e-Sehar Ali is a writer, editor and DJ. In this text, Ali explores the allure of the shape of a circle through its various manifestations across images in the Magnum archive. From everyday objects, architecture, types of dress, and our anatomies, to our impulsive physical movements and how we gather together, this text ponders the human instinct to create rounded forms throughout different cultures and contexts.

You can listen to an audio recording of this story, narrated in a special mix by Ali below:

The circle is the most alluring of all shapes. I find this allure in its form, representation, expression and beyond. Circles have always been signifiers of unity, universality and oneness. We’ve heard it all before. But there is something about my fascination with them that takes me deep into the Magnum archive to find out whether my fixation leads to a deep-seated discovery, like roots beneath the surface of an old tree, or if it is merely a case of instant gratification, like the sparks of a firework.

What is it about the circle that appeals to the human eye? What is it about a circle that inspires both connectivity and independence? And what is it about those three-dimensional transformations, the sphere and the ovoid, that appeal to the human body and mind?

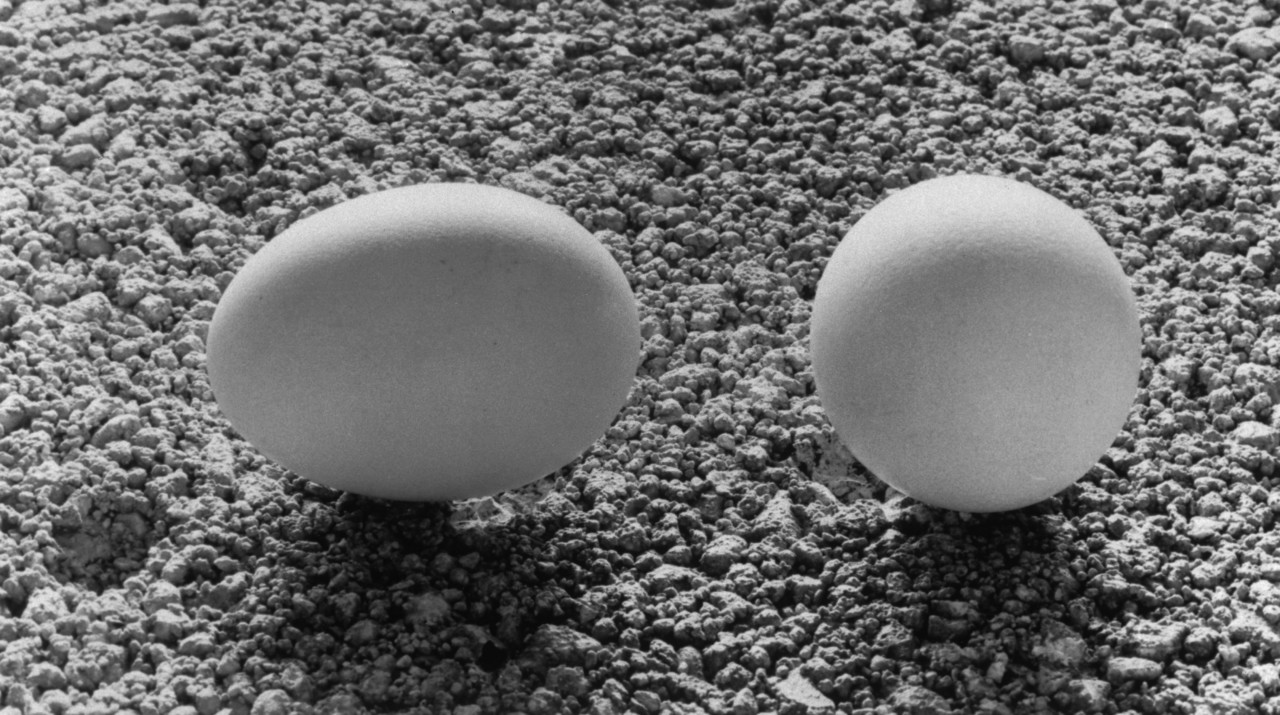

There is something about a well-rounded breast that makes me want to cup it. The glaring shine of a smooth bald head makes me want to tap it; the delicate aril that surrounds a pomegranate seed makes me want to burst it. Is there something deeper beneath these impulses? Is this impulse at the mercy of my sense of touch, felt by my curved fingertips, or is at the mercy of the sight — of something well-rounded, complete, and whole? Could it be that this impulse is a response to the power of a circle, a sphere? Perhaps it is a relationship between the two. The wholeness of a circle evokes many a response, to admire it, to play with it, to poke it, to touch it, to protect it. It evokes action, maybe because inherently, in the case of the egg, the globular brain, and the earth: activity is always pulsing.

The oh of a curve and the ah of a full circle: the semi-meridian stand in Cristina de Middel’s photograph is empty of the globe to spin within it. A curve this way is almost always lonely. Like a fishing rod that dives into the sea, pulled back with the hope of its hook met with a fish, with a prize. A curve left neglected is a curve left idle, which can only become animated by activity or hope.

A curve is a half of a circle, a unity left hanging, waiting to be met by another curve to join with its two points to become complete. When two curves unite, open end points meet and dissolve into a stream, allowing connectivity, motion and continuity. Could it be that something similar happens when we hug one another?

In contrast to the inactive curve, in Emin Özmen’s photograph, we see children joyfully at play. Remnants of tragic violence mark the wall behind them. They are captured completely in motion, oscillating on pendulum swings, hanging off a metal bar, laughing as they balance on the see-saw. Seeing these boys at play, hanging and swinging through curves, is a sight of resistance and hope. Their bodies being flung to and fro on these small arcs designed to please, show us: not only have they dodged the bullets – no bullets are designed for them. An air of promise hangs in the balance, much like the children on the frame; the promise of a future to be lived.

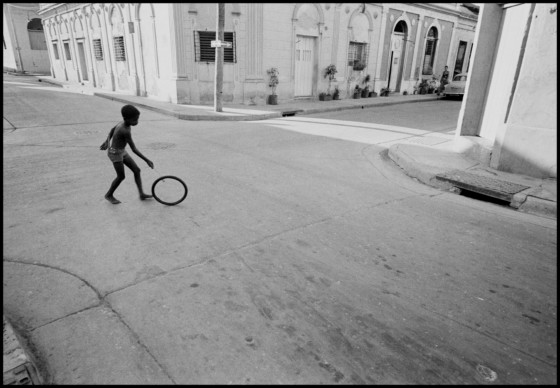

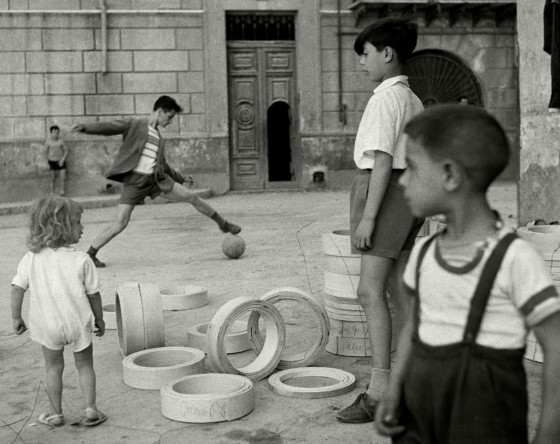

The essence of play, portrayed in Özmen’s photograph by way of the circle, is a rather familiar conceptualisation. The shape of a circle emits a merriment, an essence of the ephemeral yet eternal: especially, for example, while rolling in the company of youth.

When attempting to understand life, instead of standing under it, we tend to go over it. Maybe if we went under and over the concepts that present themselves to us as obstacles, we could do a full circle and grasp them better. The formal narratives of history may try to arrange themselves in a linear path, but the value we attach to our experiences shifts more in a circular fashion. Looking at the way we play, make love, dance, and communicate, the reality of life in its very essence may not be so straight-ahead as our attempts to rationalise.

As we grow older, we leave the playground and go to funfairs, carnivals, theme parks, we pay to go on rollercoasters, carousels and bumper cars. We swirl our lovers around in ecstatic motion. We perform a full 360° when showing off a new outfit.

Could it be that we move around in circular motion because the true essence of our being is fluid? Whilst the capitalist force of ‘bettering oneself’ is obsessed with moving forward, perhaps we find more liberation in moving around?

Ara Guler’s photographs depict dancing dervishes, spinning and whirling, grounded on the floor, balanced by their ears, elevated into transcendence through submission to the divine. Not only is it a fascinating sight, it expresses the wheels of motion that make a living thing alive, accelerated in its spin. Their arms raised upwards not only accentuate their whirl, but show how they are openly receiving a response from above. Could it be that submission, in this circularity, is always a two way deal? An exchange between us and the heavens above..

I think of Epicurus, who in about 300BCE, got there before me in his philosophy of the Atomic Swerve, who argued that, as human beings, we find liberation in moving around arbitrarily, swerving from one another, mimicking the motion of the atoms that we are made of. These circular particles dodge around one another, freely swaying and colliding, not always following and adhering.

Similarly, we dance together in ballrooms and parties, in circles and beyond, like electrons orbiting around the nucleus that protects the union of protons and neutrons. We dance to celebrate, to connect, to disconnect, to escape, to meditate, to transcend.. As we dance, we find ourselves going beyond the confines of our limbs, forming curvilinear gesticulations, animating reality with a sense of mystical reverie.

As humans we have constructed all manner of ways to provide ourselves joy, from youth to adulthood, through swiveling, chaotic movement… The first thing I am doing when I get to the afterlife is run up to Epicurus to tell him about bumper cars.

Whilst dancing exhibits circular motion in utmost acceleration, animating our limbs into wings, there are simpler forms of human behaviour that exhibit it in quieter, more innocent forms.

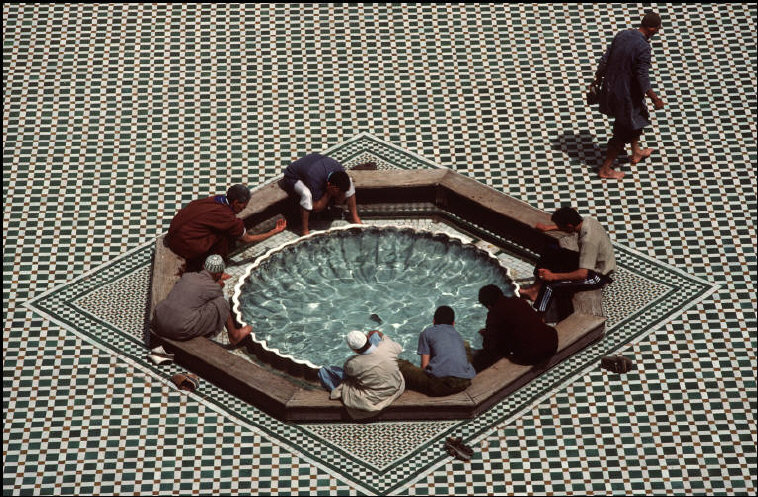

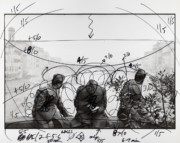

Throughout the world, human beings are part of different races, ethnicities, cultures, religions, societies, sub-societies, classes, belief systems… We have different and often opposing ways of doing things. We clash and debate, dash away and separate. Yet when we arrange ourselves in the pattern of a circle, in so many contexts, we are engaging in communication and connection.

Contemplating God, gossiping at the beach, eating, learning a certain craft, council meetings, and simply talking. The absence of corners rounds up and encloses the nourishment taking place within. This arrangement asserts ‘we are all equally a part of this space, not apart from it,’ in an attempt to defy rigid hierarchies. Even where differences in power are undeniable, like in Paolo Pellegrin’s photograph of a UN meeting, the circle appears as a balancing tool. Where one individual sits at the head of the rectangular table, they face a mural painted by Per Krohg in the style of a tapestry, in the middle of which there is a circle symbolizing, as the organization’s website suggests, the “efforts of the UN, and of mankind in general, to achieve peace, equality and freedom.”

Whilst the circular pattern can exhibit a sense of unity, equality and connection in human behaviour, its mere outline radiates independence and protection: a radiation that keeps that which is within the circle sacred. It is important to note, it is not always a boundary erected, but rather a home guarded, protected. This photograph taken by Paolo Pellegrin, of Fatima, brings to mind a hand-drawn circle. It evokes the action of drawing a circle around something whilst note-taking, to contain it. Alternately, to underline is to give it emphasis. The difference between the two is that underlining gives it a foundation to build on, circling around protects it as it is, even if simply as a peripheral means to recognise or spotlight its significance as an end in itself. Although its content is entirely empty of expression, this photograph satisfies my appetite of witnessing something beautiful. Within the framework of formalism, it meets all the demands to be considered a valuable piece of art. If I could give it a title, I would call it ‘Clive Bell’s Dream’.

The hem of Fatima’s burqa circling around her radiates both elevation and self-containment. Stood in-front of a wall spotted by sunlight, the diagonal shadow of the building on the right outlines her, careful not to intrude upon her swirl, showing us that she is not a shadow. The shadows are beside and beneath her.

Moving on from the circle’s protective outline, I find myself speculating on this protection, especially when it appears in the shape of a sphere. It was the ancient Greek philosopher Plato who posited the sphere as the most divine of all shapes, who noted how the spherical shape of our heads was created round like the shape of earth itself, to emulate the divine. And thanks to the advance of neuroscience, none can deny that the globular brain is indeed the prime location of our consciousness. Although connected with our entire anatomy, the brain is in the driver’s seat in the vehicle of our existence.

Could it be that we adorn our heads with turbans and crowns as a celebratory complement to the concentric pattern which makes up the anatomy of our heads? In the photograph by Steve Mccury, a Rabari shepherd expresses a delicate nature: I am yet to witness such fragility shine stronger than in this image, his head nestled under a mesmerising, almost glistening red turban. In Cristina de Middel’s photograph we have no insight into the nature of its subject, we see only the crown above the surface of the sea. From the humble to the sumptuous, the adornment of these circular headpieces accentuates the divinity of the fact that each mind is a universe of its own.

In these photographs by Martin Parr and Inge Morath, chandeliers dominate the frame, lighting up the scenes beneath them. Yet in this domination, the extravagance of these chandeliers highlights something deeper than their architecture. There are many sources of light in these photographs, but none overpower the inner light one feels when their mind is lit up by a gush of inspiration, an idea, a sensation. A feeling so strong, no crystal could steal its spark. Perhaps the delight of a chandelier, and its decadence, comes from a sense of recognition? It’s no wonder why we call it ‘lightbulb moment’.

The divinity of the sphere, however, goes beyond our round skulls. From sophistication to safety, the celestial arc of a dome and the sincere comfort of a hut, these circular constructions mimic the womb, nurturing those within.

What began as an alluring shape, has now become almost elusive. How can the shape of a circle lend itself to so many meanings all at once? Whilst its pattern says ‘come on in’, its outline tells you, ‘here is not where you are…’ It uninvites without offending, invites without asking. Perhaps it is this elusivity that attracts human touch, that encapsulates the rhythm of connection, from the cradle, to the playground, to rocking chairs: the circle is a shape of comfort. It’s existence takes a multitude of forms, it’s divinity innocently reaps into our lives. From the decor of rings around one’s finger, to the rings around certain planets… At times demanding our attention, at times escaping our senses.

Deep under the ground, the seed is growing, far behind the scenes, the ants are having a party. Where there is life, there is movement. Where there is movement, there is always a ball.

The very essence of being alive is motion: whether it is the atomic motion that streams through our anatomy, or the orbit of the planets above us. Where there is a circle, there is movement, where there is movement, there is always life.

Noor-e-Sehar Ali is a writer, editor, visual researcher and DJ. She is co-founder of online literary zine Lemon Curd. Her work involves advocacy for social reforms to accommodate those with varying abilities, reinforced by ongoing research in practical ethics, political philosophy and integrated studies. She is interested in the role of story-telling through a multitude of disciplines, particularly utopian narratives. Her writing is predicated upon a desire to transform the esoteric and opaque into the accessible and the lucid.

This project was made possible thanks to support from The National Lottery Heritage Fund.