Visual Storytelling and Independent Publishing: An Interview with Yumi Goto

The Reminders Photography Stronghold co-founder discusses reaching an audience through art books, and the value of a broad view of the photographic genre

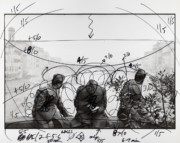

Magnum Photographers

Yumi Goto is an independent arts curator and researcher who has – since 1997 – worked in photography, at first collaborating with photographers via the Internet to distribute the e-publication pdfx12. In 2012 she co-founded the Reminders Photography Stronghold, a photographic space in downtown Tokyo focused on a broad spectrum of photographic activity – from holding exhibitions to providing grants, promoting independent book-making and providing artists with creative space.

Goto will speak during the forthcoming 5-day Tokyo masterclass in Tokyo, led by Jim Goldberg and Alessandra Sanguinetti, which will focus on visual storytelling, editing, sequencing and zine making. Here Goto discusses her route into curation, the importance of self-publishing to photographers’ practices and the rewards of a hands-on approach to photography.

More information regarding the Tokyo masterclass can be found here, and applications can be submitted here.

Early in your career you worked with PDF publications, which you shared around in those formative days of the Internet. How did you go from that online mode of curation to running a physical space for photography?

I started my photographic career in 1997, helping my husband, who is a photographer. We were still working in an analogue era back then. But later, as the Internet was beginning to be more accessible, it was becoming possible for individuals to create stories online. I extended the role I had with my husband to work with others: and in 2007 I started curating portfolios in partnership with photographers online in PDF format.

Those were early days – I worked with Mikhael Subotzky, before he joined Magnum for example. He was once a contributor to the monthly online portfolio series, pdfx12. I was working in a mobile way – not only in Japan, but moving around, and making use of the internet.

However, I was starting to get a bit tired of working in cyberspace. In 2011, when I was in Bangkok, the Great East Japan earthquake and tsunami hit. At that time my mother and husband’s mother were also very ill, so we decided to go back home, but we were not just going back for the family, we also wanted to create a physical space for our work. In 2012 we – along with photographer friends who helped a lot – set up the Reminders space. We held our first exhibition in November 2012.

The idea was to make a space that was really for photographers. The gallery space is located downtown, and some people felt it was a bit inconvenient. For me the location didn’t matter too much. What was important was the size of the space, and that we really wanted to live in it – with the gallery downstairs and house upstairs. Since we were offering something different and unique people came, regardless of the distance.

Was the space always intended to host and support a variety of activities, as well as acting as a gallery?

Yes. We offer the space for photographers to showcase their work in for free. Alongside the gallery space we have, for example, the Reminders Grant. Interestingly the first grantee was Diana Markosian, in 2013. Since then we have had 19 other grantees. We also have a photobook library which is open to the public.

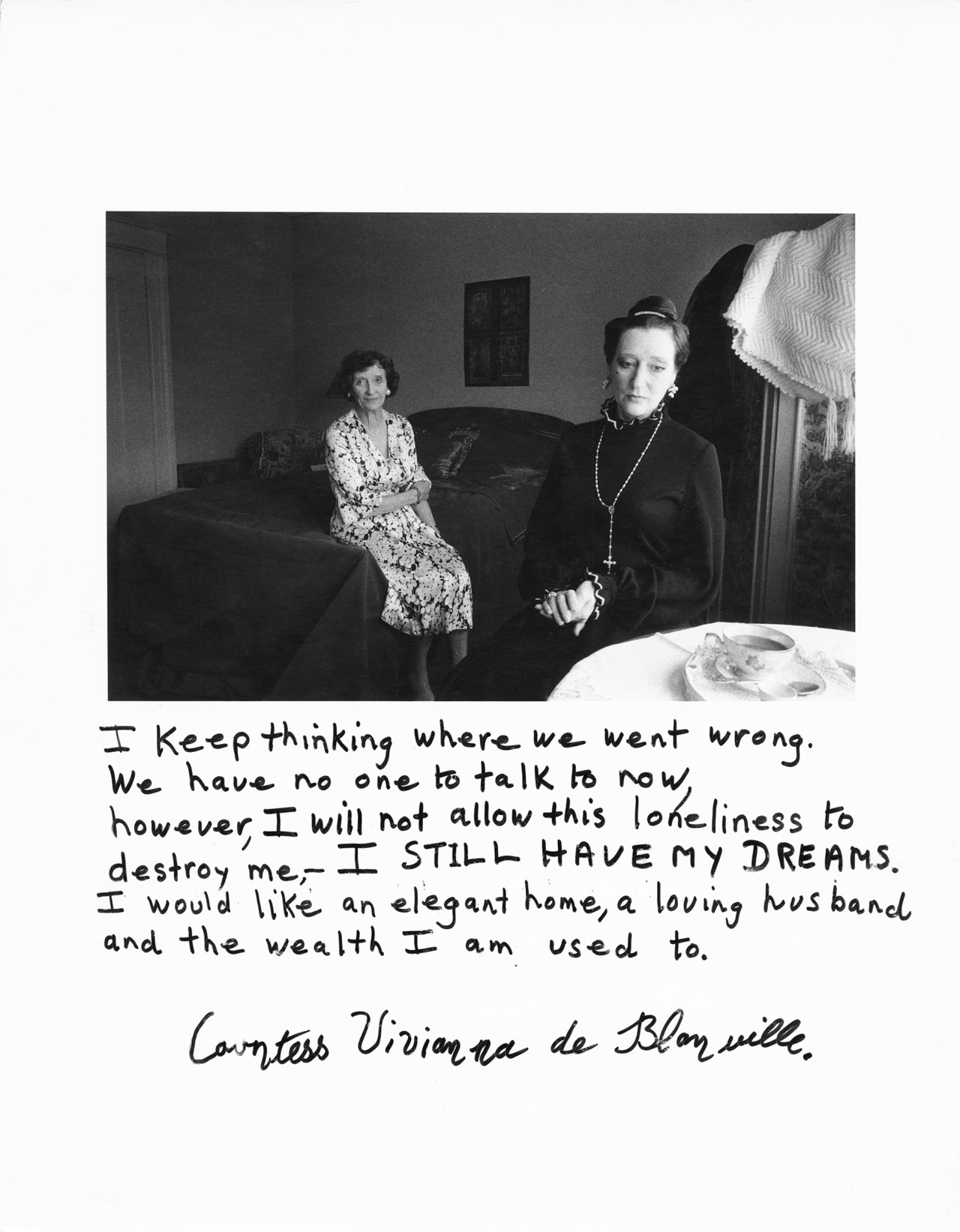

We did really want to have that physical space to exhibit work within. However, we didn’t want to just show photographs and exhibit work for purely aesthetic reasons – we wanted to work with photographers who were storytellers creating documentary work. I was still thinking, as curator, that having some pictures on a wall is nice – but I was also kind of frustrated. I wanted to do something more…

So you were thinking about how to take documentary photography beyond the limits of traditional displays or exhibitions?

Yes. I participated in a Dutch photo festival, Noordelicht. While there I dropped by a book-making workshop in The Hague and met the Belgian artist and visual story-teller Jan Rosseel. He told me that he had finished his graduation project and made a book of it, when he told me the story of this book I was amazed.

He had made 28 copies of the book, Belgian Autumn. That specific number – 28 – was taken from the subject matter itself: the book was about Belgium in the 1980s, specifically about a gang (who came to be known as ‘The Gang of Nivelles’ or ‘The Crazy Brabant Killers’) that committed a series of increasingly violent robberies around the area of Brussels. 28 people were eventually killed in these robberies. One of those victims was the artist’s own father. The case has never been solved. Rosseel brought me the last remaining copy of the first 28 books. It has since been re-released in larger number and a different format by the Belgian publisher, Hannibal Publishing, which included new materials added after further research.

It was really the type of format I was looking at becoming involved with. It was not only photography: the work included research, documents, and he had recreated images and scenes from eye-witness accounts.

Do you think that sort of photobook allows for greater flexibility in telling complex stories?

You can really intellectualise the subject. Rosseel carried out in-depth research. The number of editions of the book was equal to the number of the gang’s victims. The books were bound with number-stamped rubber bands. For me, those sorts of details have very special meaning… He was already planning to travel to Japan for a family vacation, so we met while he was there in 2014 and I invited him to do a workshop with me. That’s how we started the photobook workshops.

Even with installations (we have shows every month) one can try to create a kind of space where you can sense the story, not only by looking at nice images. With more varied materials you can get greater understanding of a subject, and relate to it more.

Is that non-photographic material ever more important than the photos themselves?

Such materials support the photos. This can be challenging for some photographers, because some only want to show their photographs. But this is a decision for them. Sometimes photographers think that they need more than just photographs. For me… the story is more important than the photo at times.

I’m interested in working more within the situation in Japan, right now. There are so many social problems, and I think it’s important we document them. This is something I’m focusing on working with more Japanese photographers on.

What are the aims of your workshops?

People say we are doing something very new. We are not trying to follow a traditional path – we are not only trying to find the best way to tell these stories, but also to sustain photographers.

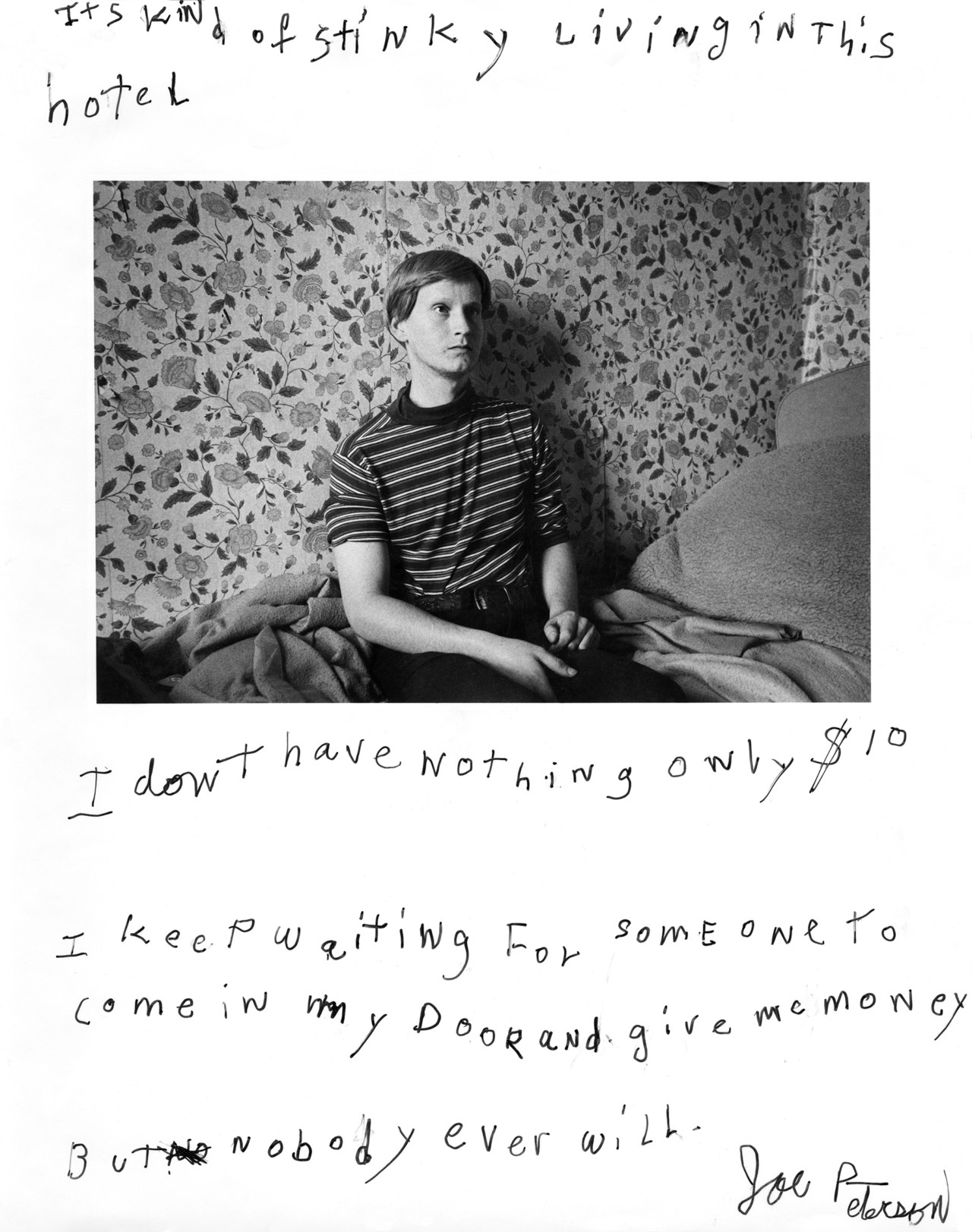

For the photobook-making workshop, we encourage participants to make dummies and enter them into competitions, as well as to present them at the any showcase outlets. We also encourage them to make artist books in the way Rosseel did, so they do all the production by themselves, from the printing to the binding. Then we help distribute the books. They should know that their work deserves to be appreciated, and that there is an audience that’s happy to pay for it. So, while participants pay for the workshop, I believe they get more back than they paid in.

What’s your favourite part of editing new books with photographers? And what are the surprises?

Many people want to participate in the workshops because they believe that if they participate then they can suddenly make a nice book – they think there must be some miracle or magic in the workshop, but there’s not really. Participants must always work very, very hard – if they do then that’s why they can make very significant books.

We are in the position where we can only guide them, and encourage them to carry on. They actually have to take on that challenge. There are some cases where [participants] just disappear, then there are those who come much further than I expected.

And what are the considerations or advantages in hand when it comes to publishing independent books with photographers?

We encourage them to make artist books in limited numbers. After the initial run we may reach out to a publisher. For us the key thing, the real focus, is that the book is exactly what the artist wants it to be. That it is not compromised – it’s really important to have the voice of the artist in this conversation in that early stage.

In the very first workshop we did, a participant named Kazuma Obara made a book about the war in the Pacific. In 1945 it wasn’t only Nagasaki and Hiroshima that were bombed, the United States carried out extensive bombing all over Japan. Obara made a story about the people of Osaka who had survived the bombing of their city. The story of those people and the historical events.

He made 45 copies of the book, by hand. It was called Silent Histories. The book got shortlisted for the Paris Photo-Aperture Foundation Photobook Awards, in 2014. He then worked with the publisher Editorial RM, who agreed to make 1900 copies. What I like is the organic nature of such collaborations: the artist works to produce the ideal dummy, then the publisher works to produce the book and distribute it. We simply aim to work with someone for the best results, and so that there is benefit for both sides.

What are the respective advantages of self-publishing versus working with a publisher when it comes to reaching an audience?

Even with self-publishing you can reach the mainstream, right? Kazuma only made 45 copies at first. But then you know that people actually start talking about the books and that those people really care for the subject matter. 45 copies is a very small number, but outside of those 45 people with the book, many others are talking about it. This is very important. You don’t have to publish 2000 copies of a book to have 2000 people talking about a topic, though of course if a publisher wants to make 2000 then that’s great!

Is the intimate distribution process important to photographers?

The process of distribution is interesting. Before they make a book the photographers often have almost no confidence. OK, they’ll make a book, but think, “Who will buy this?”

Then they get a first order, a second, a third … They get orders from people they never even thought about and they gain confidence. I often have to say stuff like, ‘Please don’t sell your books to your friends!’ I really hate that – when an artist lacks confidence they say, ‘When I make a book my friends buy it’… You should really look outside your friendship group. You are not making your book for your friends.

You should know that you have an audience, a new audience you have never thought about. Particularly for books which convey important stories.